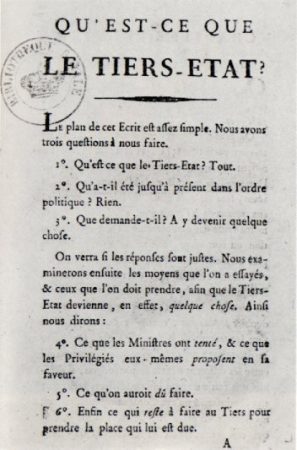

What is the Third Estate? is a political essay published in the first weeks of 1789, following the convocation of the Estates General. It was penned by Emmanuel Sieyès, a mid-ranking churchman of liberal political views. Using plain language and uncomplicated arguments, What is the Third Estate? became one of the French Revolution’s most significant political essays. It convinced untold numbers of French citizens that the Third Estate not just of their right to political representation but also, their importance to the nation.

Summary

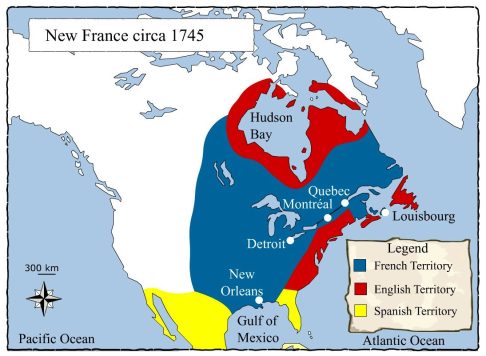

In late 1788, the French king Louis XVI announced the convocation of the Estates General, Bourbon France’s closest equivalent to a national parliament. The king also called for the submission of cahiers de doleance, or compilations of public opinion about the state of France and suggested improvements.

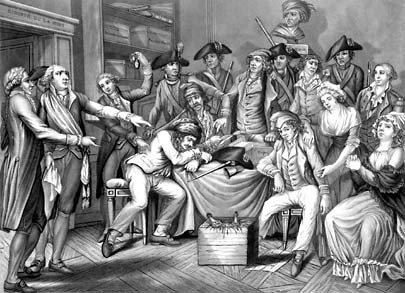

These announcements unleashed a flood of political opinion. In the wake of the king’s announcement, hundreds of essays and political pamphlets were published and circulated. Many speculated about the composition, procedure and possible outcomes of the Estates General. Some of these documents demanded equality and greater representation for the Third Estate, France’s common people. One pamphlet, written by a middle-ranking clergyman, inflamed these political aspirations more than any other.

Emmanuel Sieyès‘ Qu’est ce que le tiers etat? (‘What is the Third Estate?) struck a chord with France’s disgruntled lower classes. Asking three rhetorical questions and employing clear but forceful language, What is the Third Estate? seemed as rational and logical as it was compelling. It challenged traditional conceptions of nation and government while urging its readers not to accept hollow promises or compromises. What is the Third Estate? proved enormously popular and became what one historian calls “a script for revolution”.

Who was Emmanuel Sieyès?

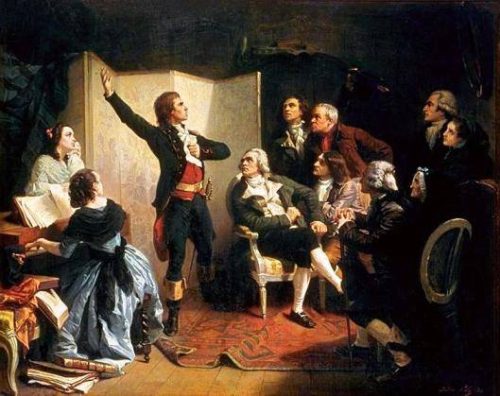

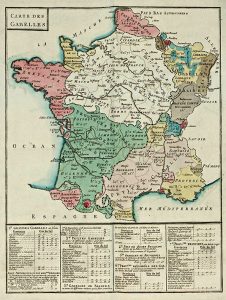

The author of this remarkable document was Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, a free-thinking clergyman. Sieyès was born in south-eastern France in 1748. His parents had noble ancestry but by the time of his birth, Sieyès’ family was barely middle class. His father was a public servant and devout Catholic who wanted his children, including middle son Emmanuel, to enter the clergy.

Sieyès received a Jesuit education before relocating to Paris, where he entered a seminary in suburban Paris and studied theology at the prestigious Sorbonne. Sieyès was a mediocre theology student, often finishing with low grades. he showed a much greater interest in liberal political philosophy, particularly the works of John Locke. A voracious reader, in 1770 Sieyès compiled a list of hundreds of books he wished to read – if he ever had the money to buy them – and Enlightenment texts featured heavily in this list.

Despite his liberal views, Sieyès continued with his entry into the church, being ordained as an abbé (abbot) in 1772. His career in the clergy was moderately successful but far from happy. After waiting two years for a posting, Sieyès finally obtained a position in the diocese of Chartres. He eventually rose to the offices of vicar-general, cathedral canon and diocesan chancellor.

While his own career was progressing slowly, Sieyès became acutely aware of how churchmen of noble birth but mediocre talent or application were moving quickly up the ranks. As his dissatisfaction with the church grew, so too did Sieyès’ interest in the nation’s unfolding political crisis.

The Estates-General called

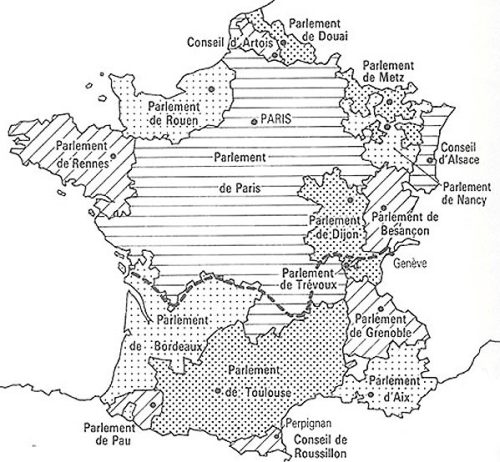

In August 1788, the king ordered the convocation of the Estates General, to sit in the middle of the following year. At this point, there was uncertainty about the composition and operation of the Estates General. The Estates General had not met since 1614, it had never followed consistent structures or procedures, and there was no constitutional instruction on what form it should take.

This uncertainty triggered a national discussion about the formation, operation and powers of the Estates General. In September 1788, the Paris parlement ruled the Estates General must adopt the same form as it had in 1614 – that is, with voting conducted by order rather than by head.

The following month Jacques Necker, who had proposed doubling the representation of the Third Estate at the Estates General, summoned an Assembly of Notables to provide advice on the matter. Government censorship was also relaxed, allowing interested parties to write openly and extensively about the forthcoming Estates General.

Sieyès pens What is the Third Estate?

All this inspired Sieyès to put pen to paper. In November 1788, he published Essai sur les privileges (‘Essay on the privileges’) which attacked the presence of privilege and exemptions in France’s society and political system. This was quickly followed by What is the Third Estate? in January 1789.

What is the Third Estate? was based on a simple premise: the Third Estate formed the majority of the nation and did the work of the nation, so it was entitled to political representation. As Thomas Paine had done in America with Common Sense in 1776, Sieyès kept the structure simple and used reasoning that was clear and accessible for ordinary readers.

In the most-quoted passage of What is the Third Estate?, he posted three rhetorical questions and answers:

“What is the Third Estate? Everything.

What has it been heretofore in the political order? Nothing.

What does it demand? To become something.”

Impact on the revolution

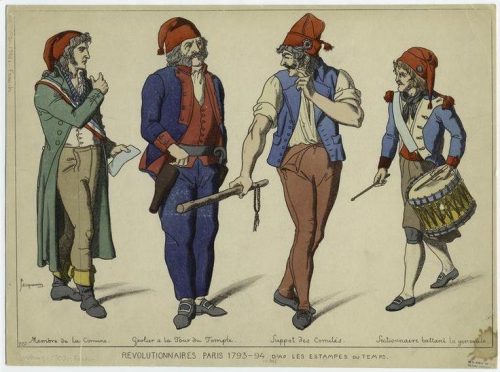

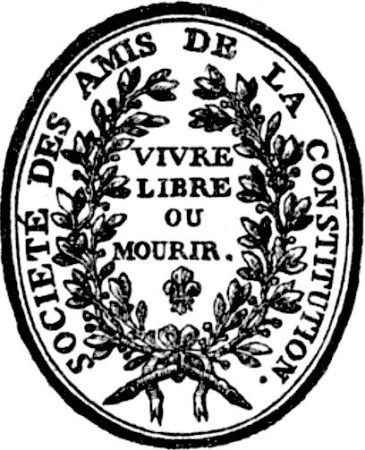

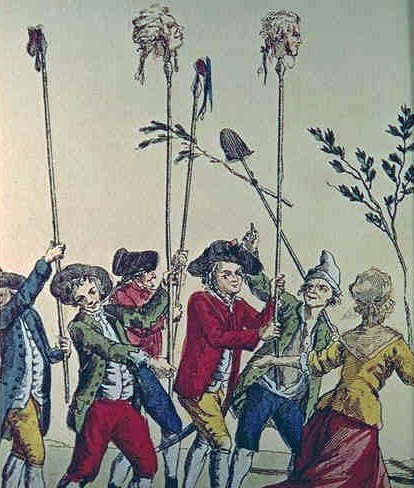

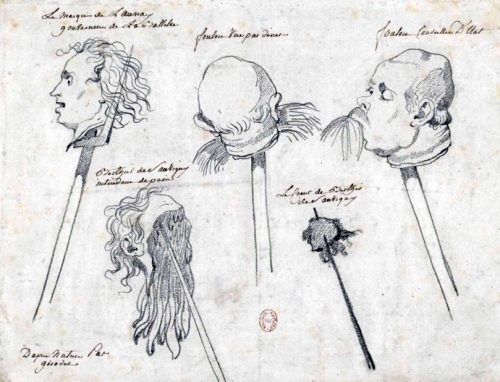

What is the Third Estate? became the most influential text of the early French Revolution. It crystallised the grievances of ordinary people in a rational and logical manner. It reminded the common French people they had been exploited and mistreated, both by an unrepresentative government and by a parasitic nobility that refused to pay its own way.

More importantly, What is the Third Estate? provided Third Estate representatives attending the Estates General with a set of objectives. Sieyès argued that Third Estate representation must be equal to or larger than the First and Second Estates combined. He called for voting at the Estates General to be conducted by head (that is, by a tally of individual deputies) rather than by order (the Estates voting in blocs).

These arguments shaped the demands of the Third Estate at the Estates General, culminating in their decision to break away to form the National Assembly. It is uncertain whether this would have occurred without the public debates and the impetus for change sparked by What is the Third Estate?

“Sieyès – who had an ear for what we would now call the sound-bite – gave a notorious answer to this question [of political representation]. In contrast to the other two orders, the nobility and priesthood, which he claimed were guardians of their own corporate privilege, the Third Estate had ‘no corporate interest to defend… it demands nothing less than to make the totality of citizens a single social body.’ It was, he claimed, not one order amongst others, but itself, alone, ‘the nation’: it was ‘everything’.”

Iain Hampsher-Monk, historian

What happened to Sieyès?

For Emmanuel Sieyès, the impact of What is the Third Estate? brought him considerable respect and popularity. In March 1789, he was elected to represent the Third Estate at the Estates-General, despite Sieyès being a member of the First Estate and having no experience as an advocate, debater or public speaker.

Sieyès rarely gave public addresses during the Estates General but worked diligently behind the scenes and was often consulted for advice or instruction. When the Third Estate and its allies re-formed as the National Assembly on June 17th, Sieyès personally introduced the motions to initiate this change. The rest of Sieyès’ political career never reached similar heights. He served in both the National Constituent Assembly and the National Convention, participating mainly in constitutional discussions and drafting.

Ultimately, Sieyès was not radical enough for the revolution he had helped unleash. He desired a constitutional monarchy and a bourgeois democracy rather than a popular republic, nor could not bring himself to attack the church as he had attacked the nobility.

1. What is the Third Estate? was one of the French Revolution’s most significant and influential political texts, shaping the course of events in 1789.

2. Its author was Emmanuel Sieyès, a middle-ranking clergyman and free thinker who had studied Enlightenment political philosophy and was frustrated by nobility and privilege.

3. Sieyès penned What is the Third Estate? in late 1788, in the midst of a ‘pamphlet war’ over the composition, procedures and outcomes of the Estates General.

4. In What is the Third Estate? Sieyès argued that commoners made up most of the nation and did most of its work, so therefore were the nation. He urged members of the Third Estate to demand a constitution and greater political representation.

5. The ideas contained in What is the Third Estate? were instrumental in shaping the events of 1789, particularly the formation of the National Assembly, while Sieyès himself became a political delegate in the new regime.

Extracts from What is the Third Estate? (1789)

Citation information

Title: ‘Sieyès and What is the Third Estate?‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/sieyes-what-is-the-third-estate/

Date published: October 20, 2019

Date updated: November 9, 2023

Date accessed: May 17, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.