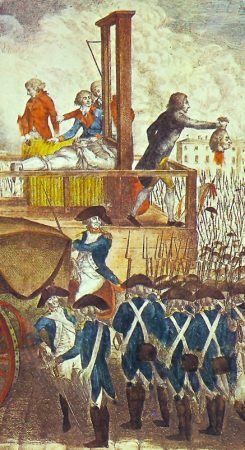

The French Revolution had almost everything we associate with revolutions – ravenous royals, ambitious aristocrats, rising taxes, failing harvests, food shortages, hungry peasants, angry townspeople, sex, lies, corruption, mob violence, radicals and weirdos, rumours and conspiracies, state-sanctioned terror and gory head-chopping machines.

The French Revolution was not the first revolution of the modern era but it has become the measure against which other revolutions are weighed. The political and social upheaval in 18th century France has been studied by millions of people, from scholars on high to students in high school. The storming of the Bastille on July 14th 1789 has become one of the defining moments of Western history, a perfect motif of a people in revolution. The men and women of revolutionary France – Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, Marquis de Lafayette, Honore Mirabeau, Georges Danton, Jean-Paul Marat, Maximilien Robespierre and others – have been researched, studied, analysed and interpreted. Historians have spent more than two centuries evaluating the French Revolution, trying to decide if it was a leap of progress or a descent into barbarism.

At first glance, the causes of the French Revolution seem straightforward. By the late 18th century, the people of France had endured centuries of gross inequality and exploitation. The prevailing social hierarchy required French commoners, the Third Estate, to perform the nation’s work, while also shouldering its taxation burden. The king lived in virtual isolation at Versailles, his royal government absolutist in theory but ineffectual in reality. The national treasury was almost empty, drained by grossly mismanagement, inefficiency, corruption, profligate spending and involvement in foreign wars.

Alpha History’s French Revolution website is a comprehensive textbook-quality resource for studying events in France in the late 1700s. It contains more than 500 different primary and secondary sources, including detailed topic summaries, documents and graphic representations. Our website also contains reference material such as maps and concept maps, timelines, glossaries, a ‘who’s who’ and information on historiography and historians. Students can also test their knowledge and recall with a range of online activities, including quizzes, crosswords and wordsearches. With the exception of primary sources, all content at Alpha History is written by qualified teachers, authors and historians.

Aside from primary sources, all content on this website is © Alpha History 2018-23. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without the express permission of Alpha History. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.