The sans-culottes is a term describing the working classes of Paris who participated in the great journées of the French Revolution. Identifiable by their clothing, their radical political views and their frequent use of violence and intimidation, the sans-culottes became the face of the radical revolution of the 1790s. There remains, however, considerable debate about who the sans-culottes actually were.

Who were the sans-culottes?

Chroniclers, novelists and historians have given us many depictions of the Parisian working class. Some have fallen into stereotype while other depictions remain hotly debated.

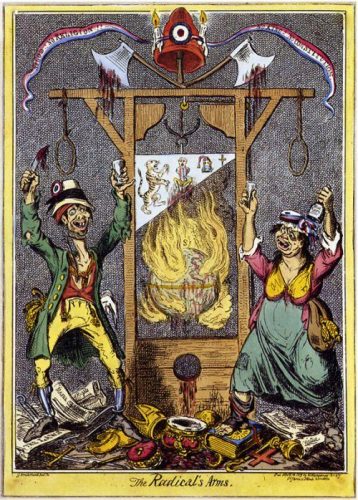

To some, the sans-culottes were an amorphous but brutal mob, seething with discontent, susceptible to rumour and gossip, hell-bent on achieving their aims with violence. Other historians, like George Rudé and Albert Soboul, have deconstructed the identities, motives and methods of the sans-culottes and found greater complexity.

Whatever the interpretation of the sans-culottes and their motives, their impact on the revolution, particularly between 1792 and 1794, is undeniable.

Etymology

The term sans-culottes is French for ‘without britches’. It was initially a humorous term, referring to a young man caught in an embarrassing situation with a woman.

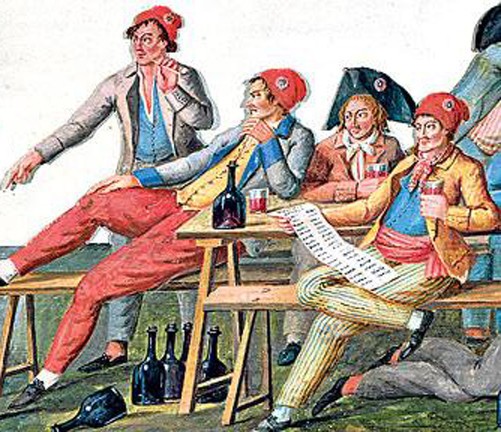

Sans-culottes first appeared in a political context in 1790, to describe townsmen who wore pantaloons (long trousers) instead of the knee-length britches favoured by the nobility and wealthy bourgeoisie. It was first used in royalist newspapers, to ridicule working class members of the Jacobin club.

Before long the phrase sans-culottes was in common use, describing urban workers, artisans or small businessmen, especially those who supported the revolution. Later, the popular perception of a sans-culotte was a political radical from the working classes and sections of Paris.

Composition

The sans-culottes were uniformly working-class: most either laboured for wages or ran their own small stores or businesses. They lived in the poorer suburbs of Paris, most notably Faubourg Saint-Antoine and Faubourg Saint-Michel in the city’s east.

A minority of sans-culottes were politically active, at least in an organised sense. They were most commonly found in the 48 sectional assemblies that made up the Paris Commune. Of the 1,361 deputies who sat in these assemblies in 1793-94, more than two-thirds were tradesmen or shopkeepers. Others attended the sectional assemblies as spectators or hecklers. Some also attended meetings of the political clubs – most notably the Society of Cordeliers, which was open to all, and later the Jacobins.

The majority of sans-culottes, however, remained outside organised politics. They obtained their political news from the inflammatory press and secondhand reports, which of course made them susceptible to rumour and conspiracy theories.

The sans-culottes could also be roused to action by orators and propagandists. An example of this was the journée of May 31st 1793, which culminated in the expulsion of Girondin deputies from the National Convention.

Intimidation and violence

The hallmark of the sans-culottes was their capacity for forcing change with threats and violence. Working-class mobs were involved in just about every significant journée in revolutionary Paris. They laid siege to the house and factory of Réveillon in April 1789. Three months later they attacked the Bastille, butchered its governor and dismembered the royal minister Joseph-François Foullon.

In October 1789, the sans-culottes, many of them women, marched on Versailles, menaced the royal family and forced the king to return to Paris. They massed on the Champ de Mars in July 1791 to sign Republican petitions, dozens dying from the gunfire of the National Guard.

In August 1792, Parisian sans-culottes invaded the Tuileries palace alongside Republican troops and, once inside, participated in the slaughter of the Swiss garrison. On the same day, they surrounded the Legislative Assembly and coerced it into suspending the monarchy. The following month (September 1792), sans-culottes raided the prisons of Paris and ‘cleansed’ them of counter-revolutionaries and traitors, one of the bloodiest incidents of the entire revolution.

Political aims

What were the political aims of the sans-culottes? For the most part, they were democratic, egalitarian and wanted price controls on food and essential commodities. Beyond that, their aims are unclear and open to conjecture.

Some historians have categorised sans-culottism as a petit bourgeois movement, dominated by tradesmen and small business owners. Gwyn Williams researched 450 influential sans-culottes leaders and found that almost two-thirds were artisans and shopkeepers, while only one in ten was a wage earner. They were not anti-capitalist, Williams contends, nor were they opposed to wealth or private property, only its concentration in the hands of a privileged few.

In contrast, the socialist historian Albert Soboul sees the sans-culottes as class warriors. They were ‘Marxists before Marx’ who sought to destroy the aristocracy and remake the world along socialist lines. Revisionists like Alfred Cobban reject the suggestion that the sans-culottes were themselves a social class or even a homogenous group. There was too much diversity in their ranks, their motives were often unclear, and they usually responded to events rather than leading or creating them.

The sans-culotte cult grows

Whatever the realities of the sans-culottes movement, it was undoubtedly coloured by idealism and propaganda.

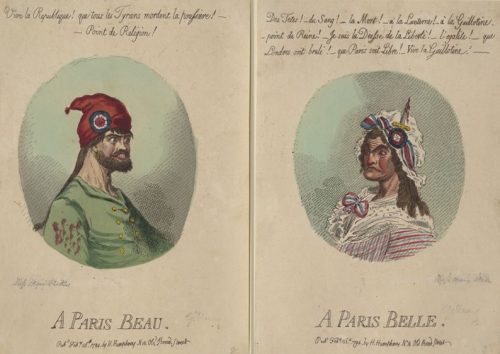

By the autumn of 1793, the Jacobins and their supporters were beginning to embrace a cult of democracy and egalitarianism. At the centre of this were the sans-culottes, who were celebrated as working-class heroes and the political vanguard of the revolution. Propagandists painted a stereotype of the typical sans-culotte: hardworking and humble, politically alert, watchful and prepared, always ready to take up arms to defend the revolution.

A well known epigram, published by Antoine-François Momoro in 1793, asked and answered the question “What is a sans-culotte?”:

“A sans-culotte, you rogues? He is someone who always goes about on foot. [He] has not got the millions you would all like to have… [He] has no chateaux, no valets to wait on him… He is useful because he knows how to till a field, to forge iron, to use a saw… and to spill his blood to the last drop for the safety of the Republic… In the evening he goes to the assembly of his Section, not powdered and perfumed and nattily booted, in the hope of being noticed by the female citizens in the galleries, but ready to support sound proposals with all his might, and ready to pulverise those which come from the despised faction of politicians. Finally, a sans-culotte always has his sabre well-sharpened, ready to cut off the ears of all opponents of the Revolution.”

The ‘purest revolutionary’

As this stereotype took hold, the sans-culotte was hailed as the backbone of the revolution and the purest type of revolutionary. Whether by choice or necessity for self-preservation, many in Paris began to actively mimic the sans-culottes.

Those who wished to demonstrate their support of the revolution, whatever their own class, began dress in the garb of the sans-culotte: long-legged trousers, a short-tailed carmagnole coat and the bonnet rouge or ‘liberty cap’. Formal modes of address like “Monsieur”, “Madame” and “Mademoiselle” were abandoned in favour of the more egalitarian and patriotic “Citoyen” and “Citoyenne”. Those who refused to embrace this adoration and mimicry were open to suspicion.

While perceptions of the sans-culottes shaped revolutionary culture, by late 1793, the political influence of the sans-culottes was beginning to wane. The National Convention was now dominated by Maximilien Robespierre and the Jacobins, who moved to centralise their power and unfurl the Reign of Terror. This involved some curtailment of sans-culotte political activity.

In September, the government limited sectional assemblies to a maximum of two five-hour meetings per week. The Convention also nobbled the autonomy of the Paris Commune, the other institutional beacon for Parisian radicals. There were attempts to mobilise the sans-culottes in 1794 and 1795 but these lacked the impact of earlier journées.

“The sans-culottes often estimated a person’s worth by appearance, deducing character from costume and political convictions from character; everything that jarred their sense of equality was suspect of being ‘aristocratic’. It was difficult, therefore, for any person of the old regime to find favour in their eyes, even when there was no specific charge against him. ‘For such men are incapable of bringing themselves to the heights of our revolution; their hearts are always full of pride and we shall never forget their former grandeur and their domination over us.”

Albert Soboul, historian

1. The sans-culottes were the working class people of Paris, so named because they wore long trousers (pantaloons) rather than the knee breeches favoured by the aristocracy.

2. The leaders of the Parisian sans-culottes were found in the sectional assemblies and the Commune, particularly after August 1792. Most sans-culottes themselves, however, were not involved in organised political groups.

3. Broadly speaking, the sans-culottes wanted a democratic government with universal suffrage, as well as price controls on food and other essential goods. Their aims beyond that are a matter of debate.

4. The sans-culottes are best known for their use of mob violence and intimidation to bring about political change. They were involved in almost all of the violent journées in Paris during the early 1790s.

5. During the radical period in 1793-94, propaganda and popular culture hailed the sans-culottes as the humble vanguard of the French Revolution. Their political impact, however, was negated by the growing centralisation of Jacobin power.

Citation information

Title: ‘Sans-culottes’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/sans-culottes/

Date published: September 24, 2019

Date updated: November 10, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.