In 1792, the Legislative Assembly declared revolutionary war against France’s neighbour, Austria. The French Revolutionary Wars would have a profound effect on the new society. They would shape the course of European history, these wars rolling one into the other and lasting a decade – or more than two decades, if one counts the Napoleonic Wars that followed. At various times, the French Revolutionary Wars would involve almost every significant European power. Inside France, the new regime came to be defined by war and the problems, pressures and paranoia that it created.

Reasons for war

The French Revolutionary Wars had many parents: anti-revolutionary paranoia in Europe, agitation and sabre-rattling by French émigrés, foreign concerns about the fate of Louis XVI, the king’s personal agenda, belligerent propaganda and the internal politics of the new regime.

When the French Revolution erupted in 1789, the crowned rulers of Europe watched it with a mixture of scorn, excitation and fear. Some considered the revolution nothing more than a localised insurrection, destined to eventually burn out. Others watched the uprising in France more cautiously, concerned that it might spark a similar uprising in other kingdoms.

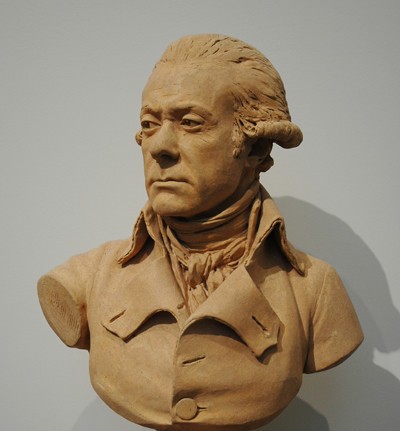

The most pivotal figure outside France was Leopold II, brother of Marie Antoinette and newly crowned ruler of the Holy Roman Empire. More progressive than his fellow princes, Leopold admired the Enlightenment and its concepts of constitutional government and natural rights. He was initially sympathetic to the French Revolution, believing the formation of a constitutional monarchy in France might prolong his brother-in-law’s tenure on the throne.

Europe takes action

Leopold II spent his first months on the throne batting away the pleas of French émigrés and trying to avoid a military entanglement in France. He became more interested in France in the summer of 1791, after Louis XVI’s ill-fated attempt to flee Paris left the French king in a more precarious position.

In July 1791, Leopold instigated the Padua Circular, an open letter to the leaders of Prussia, England, Spain, Russia, Sweden and other nations. This circular called for a European military coalition to invade France, halt the revolution and reinstall the monarchy.

The Padua Circular was followed by the Declaration of Pillnitz (August 27th 1791), a joint statement by Leopold and Frederick William II, King of Prussia. The declaration was both a rallying cry to European princes and a warning to the French revolutionaries.

The Declaration of Pillnitz was more bluff than challenge, however, since Leopold still had no desire for war with France, and nor did his European allies. It did not garner much attention in France either, at least not until the rise of the pro-war Girondinist faction.

“According to convention, France went to war in 1792 in a bid to save the Revolution by exporting her principles to the rest of Europe. In reality, such an explanation is at the very least inadequate… nothing was easier for the Brissotins [Girondins] than to cultivate a war they believed would republicanise France, redoubled by the belief that the ancien regime’s armies would flee in terror, that war could be restricted to Austria alone, and that a war would ease France’s numerous economic problems.”

Charles J. Esdaile

The Girondin case for war

Historians have long debated why the Girondins wanted war in 1791-92. The consensus now is that they wanted to militarise the revolution, to provide it with direction and impetus, to distract from domestic economic problems and to consolidate their own power. A war with Austria would, they hoped, ignite French patriotism and reinvigorate revolutionary sentiment. It would also test the loyalty of the king.

Could France win such a war? The Girondin deputies certainly believed so. Austria was weak and her leader was new to the throne and reluctant to fight. Prussia was a rival of Austria, the Girondins assured the Legislative Assembly, so was therefore unlikely to join a coalition. Britain, Russia and Sweden had their own problems and would not entangle themselves in a war against France.

Some Girondins also believed that a revolutionary war would become a “crusade for universal liberty”, as Jacques Brissot put it. “Each soldier will say to his enemy: ‘Brother, I am not going to cut your throat. I am going to free you from the yoke under which you labour. I am going to show you the road to happiness’.”

War declared

These fine words won the day. In March 1792, Leopold II died suddenly and the Austrian throne passed to his 24-year-old son. Seizing the moment, the Girondin ministry began preparing and agitating for war.

On April 20th 1792, Louis XVI attended a session of the Legislative Assembly and sat through speeches calling for a preemptive war. The king then rose and formally declared war against Austria and Emperor Francis II, the nephew of his wife.

It is likely the king wanted war for his own reasons, perhaps hoping the combined might of Austria, Prussia and the émigré forces would drive the revolutionaries from power and restore him to the throne. The Marquis de Lafayette also wanted war; he believed it would correct the revolution, revive the monarchy and restore his own prestige.

Problems in the army

France’s plunge into war was initially disastrous, in part because the nation’s armed forces had been compromised and weakened by the revolution and its ideas. The events of 1789 had fostered poor discipline and insubordination in the ranks of the army. Enlisted soldiers established ‘political committees’ to protect their rights and some grew surly and defiant.

Experienced officers, many already frustrated by the events of the revolution, despised this breakdown of discipline in the ranks. Many officers fled France to become émigrés or simply abandoned the military altogether. Officers who stayed tried to restore discipline with harsh punishments, chiefly detention and floggings, which only made matters worse.

In the spring and summer of 1790, the royal army was beset by a series of mutinies. In August 1790, the garrison in Nancy mutinied, a protest against the National Constituent Assembly’s decision to prohibit political committees in the army. The government sent a 4,500-strong force to crush the mutiny and two dozen of its ringleaders were executed.

France faces invasion

By the time the Legislative Assembly declared war in April 1792, the national army was in a parlous state. France’s leading military commanders – including Lafayette, Count Rochambeau and Marshal Lucker – had little confidence in the army and its capacity for war.

Initial engagements seemed to confirm this. General Charles Dumouriez hastily organised an offensive against Austrian-controlled Belgium in late April. It ended in disaster, with French revolutionary troops fleeing the battlefield and murdering one of their own generals.

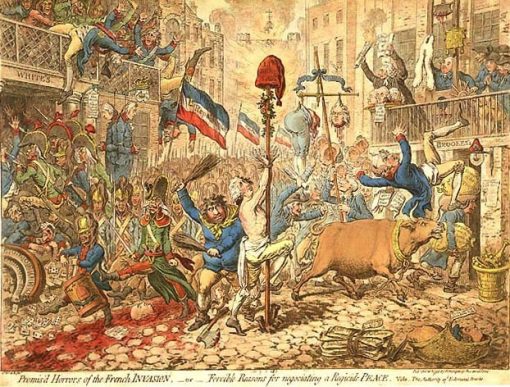

By the start of summer, a combined force of Austrians, Prussians, Hessian mercenaries and émigrés was gathering along the Rhine and preparing to invade France. On July 25th the Prussian commander, the Duke of Brunswick, issued his famously provocative manifesto, threatening Paris with destruction.

Four weeks later the Allies crossed the French border, overran Longwy and Verdun, and prepared to march on Paris. These events caused panic in the capital, contributing to the journée of August 10th and the massacre of prisoners in early September.

Fortunes change

Just as Paris and the revolution looked hopelessly lost, Dumouriez instigated a daring but effective manoeuvre to halt the advance. A series of flanking moves, followed by the formation of defensive lines, slowed the Allied progress.

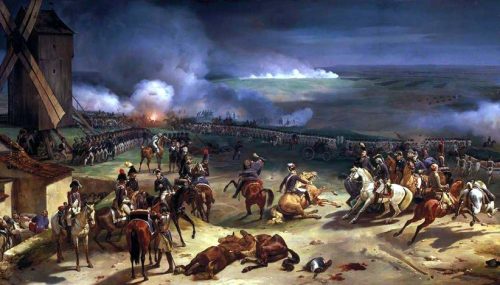

On September 20th 1792, a French force exceeding 30,000 men engaged the invaders at Valmy, halfway between Paris and the border. Amid drenching rain and thick mud, the French outmanoeuvred and outfought Brunswick’s coalition force, which by the following day was in retreat. Within two weeks, the Allied army had withdrawn from French territory and the revolution appeared to have been saved. Dumouriez was hailed as a hero and the new National Convention – which assumed the reins of government on September 20th, the day of the battle at Valmy – moved to abolish the monarchy.

Valmy marked a turning point in French military fortunes but the necessities and problems of war continued to shape both France’s relationships abroad and the course of the revolution at home.

1. War played a significant role in shaping the course of the French Revolution. War with Europe was declared in 1792 and continued for the rest of the revolution and beyond.

2. Within the Legislative Assembly, the Girondins agitated for war for several reasons. They hoped to militarise and energise the revolution, gain public support and consolidate their own power.

3. One of Revolutionary France’s adversaries was Austria. Its king, Leopold II, was initially sympathetic to the revolution and reluctant to initiate a long and costly war with France.

4. The Girondins eventually declared war in April 1792. The first months of the war were disastrous, due to poor discipline and unrest in the army, in part due to the revolution.

5. The French revolutionaries suffered some humiliating defeats but managed to stem the tide in September 1792, defeating the Austrians and Prussians at Valmy and forcing them to retreat from French territory.

Citation information

Title: ‘Revolutionary war’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/revolutionary-war/

Date published: September 24, 2019

Date updated: November 10, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.