The Paris Commune was the municipal or city government of Paris, formed during the insurrection of July 1789. Dominated by liberal moderate figures in its first three years, the Commune was overthrown and replaced on August 1792, becoming more representative of working-class interests and political radicalism. From this point, the Commune became an important body in a fast-radicalising revolution.

A barometer of the revolution

The Commune played an important role in the life of the capital. Not only did it provide civic functions like tax collection, services and public works, the Paris Commune was also a democratic assembly where the ordinary people of Paris were represented. This gave the Commune a great deal of sway. It also made it a barometer of political and revolutionary sentiment.

During the French Revolution, membership of the Commune council reflected the political will of the people of Paris. In its first three years, the Commune was dominated by the urban bourgeoisie and liberal-moderates like Jean-Sylvain Bailly. After the journée of August 10th 1792, control of the Commune was seized by radical Jacobins like Georges Danton, Camille Desmoulins and Jacques Hébert.

From this point the Commune became directly representative of the Paris sections and sans-culottes. The actions of this radical Commune challenged the authority of the national government and shaped the violence of 1792-94.

Origins of municipal government

The municipal government of Paris had its origins in the mid-14th century when the city was effectively run by merchants.

By the 1780s, the Paris city council was called the Bureau de la Ville. It was headed by the Prévôt des Marchands (‘Provost of Merchants’), the city’s de facto mayor. Despite his title, the Provost was no longer a merchant – in fact, most provosts were career public servants and administrators.

Both the Provost and the Bureau were housed in the Hôtel de Ville, an imposing Renaissance-style building on the banks of the River Seine. They carried out similar functions to modern city governments: managing the city’s budget, collecting municipal taxes and determining expenditure; overseeing the construction and repair of infrastructure like roads, bridges, wells and fountains; organising rubbish collection; naming streets, gathering census information and keeping records.

The Provost and the Bureau had a few guards at their disposal but no permanent police force.

A violent takeover

The events of 1789 caused more disruption and unrest in Paris than elsewhere in France. Much of this unrest originated in Paris’ districts. Royal edicts in early 1789 had divided the city into 60 districts, solely for the purpose of electing the Estates General. These districts had no other function but in the turmoil of 1789, they mobilised to topple the city’s municipal government.

As was common in the revolution, this was achieved with violence. On July 14th, shortly after the Bastille was breached in eastern Paris, an armed mob from the districts gathered on the steps of the Hôtel de Ville. Once assembled, the crowd demanded to hear from Jacques de Flesselles, the incumbent Provost of Merchants.

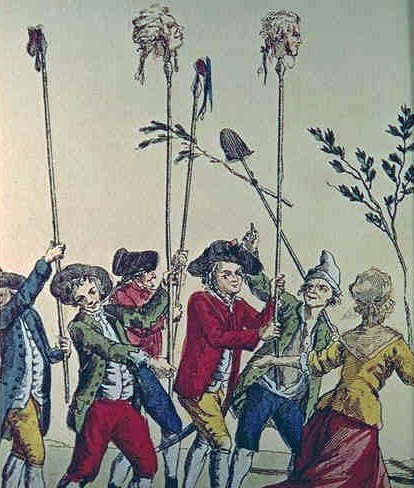

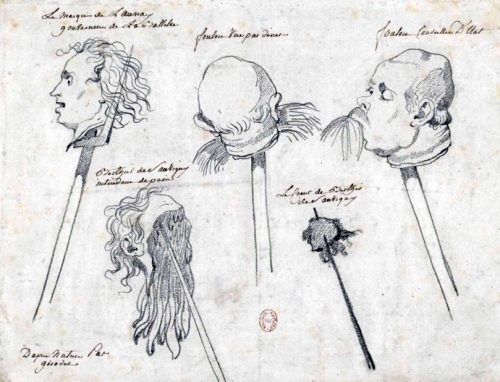

Flesselles emerged from the building and began to address the crowd but was quickly gunned down by an unknown assassin. Like the Bastille governor Bernard De Launay, Flesselles’ body was dismembered and his head paraded through Paris on a pike. Unsurprisingly, Bureau officials fled the Hôtel de Ville immediately, leaving both the building and municipal government to the mob.

Royal acceptance of the Commune

The following day, July 15th, electors from the 60 districts of Paris assembled to form a new municipal government. Jean-Sylvain Bailly, famous for his contributions to astronomy and his leadership of the Third Estate at the Estates-General, was elected as the city’s first mayor. The Commune council was chosen, comprised of deputies elected from the 60 districts of Paris.

On July 17th, Louis XVI travelled from Versailles to Paris on a goodwill visit to meet the new municipal government. The king’s visit proceeded well, despite a shot being fired at the royal carriage as it passed through the districts. Louis was met by members of the Commune, led by Bailly, who presented the king with keys to the city.

The king also attended the Hôtel de Ville, where he was presented with a large red and blue cockade; he attached it to his coat without hesitation. This gesture prompted applause, cheering and shouts of “Vive le roi!”. Later, the king agreed to dismiss his conservative ministers and reappoint Jacques Necker to his cabinet. The French monarch, it seemed, had accepted the Paris Commune and the will of his people.

The murder of Foullon

The events of July 17th, however, did not end the bloodlust in Paris. On July 22nd, some Parisians discovered one of the king’s ministers, Joseph-François Foullon de Doué, hiding in the city.

Foullon was a wanted man, for two significant reasons. The king, after dismissing the popular Jacques Necker on July 11th, had nominated Foullon as his replacement. Parisian newspapers had also accused Foullon, probably falsely, of declaring that hungry people should eat hay.

The captured Foullon was taken under guard to the Hôtel de Ville and for a time it seemed the mob would spare him. But despite speeches from Bailly and Lafayette, a frenzied mob snatched Foullon and strangled the old man in front of the Commune. His head was removed, stuffed with hay and placed atop a pike; the rest of his body was stripped and hacked to pieces.

Foullon’s body parts were then paraded around Paris. They passed Gouverneur Morris, an American revolutionary politician who was visiting France. “Gracious God, what a people!” Morris later wrote in a letter to Lafayette. “Have we gone backward centuries to pagan atrocities? And you talk of making this people the supreme authority in France? Your party is mad!”

Reorganising Paris

By late July, the unrest in Paris had settled and the new Commune began fulfilling the duties of a municipal government. Various committees were formed to oversee administration, public works, police, markets and food supplies. Special committees were formed to manage the demolition of the Bastille and the sale of its contents for poor relief.

On May 21st 1790, the National Constituent Assembly passed a law formally establishing the Commune as the governing body of Paris. This law also reorganised the city’s electoral divisions, abolishing the 60 districts created in 1789 and replacing them with 48 larger sections. These sections sent three deputies each, 144 in total, to the Commune’s General Council, where they sat for a two-year term.

The Commune also retained complete control of the National Guard, as well as a small police force or gendarmerie.

“The Commune of August 10th did not suddenly materialise out of thin air. Some sans-culottes had held office since 1790, a few even since 1789… On the whole, Commune members were a fair cross-section of working-class Paris, together with a few well-known orators from the clubs, and one or two unsavoury characters… Brought to power by force of arms, the [August 1792] Commune was able to exploit its capital of terror.”

François Furet, historian

The revolutionary Commune

The Commune remained in control of the capital through the revolution. This was particularly true after the journée of August 10th 1792, when mobs attacked the Tuileries and radicals like Georges Danton, Camille Desmoulins and Jacques Hébert seized control of the Commune and its council.

This new body, which described itself as a ‘revolutionary Commune’, was strongly influenced by the sectional assemblies and the sans-culottes. This revolutionary Commune frequently challenged the power of the national government – first the Legislative Assembly, then the National Convention. Members of the Commune had a hand in both the September Massacres (1792) and the insurrection that led to the expulsion of the Girondins from the Convention (June 1793).

For a time, Paris was ruled by an alliance between the Commune, the Jacobins and the sans-culottes. But the power of the Commune began to wane in early 1794. The assassination of Jean-Paul Marat (July 1793) and the executions of Hébert (March 1794) and Danton (April 1794) robbed the Commune of some of its most influential leaders. Meanwhile, the growing power of the Committee of Public Safety negated much of the Commune’s influence.

1. The Paris Commune was the municipal government of the French capital, formed after the overthrow of the city’s Bureau and Provost of Merchants on July 14th 1789.

2. The first Paris Commune was filled with bourgeois delegates and headed by Jean-Sylvain Bailly. It worked to establish a municipal government in Paris, hearing petitions and providing services.

3. The formal authority of the Commune came from a May 21st 1790 decree, which divided Paris into 48 sections. Each section elected three delegates to the Commune’s General Council.

4. The leadership of the Commune changed significantly on August 10th 1792, when radical Jacobins like Danton, Desmoulins and Hébert gained control of the council and declared themselves a ‘revolutionary Commune’.

5. From this point, the Commune became closely associated with the sections, the Jacobins and the sans-culottes, its actions contributing to revolutionary violence and challenging the authority of the national government.

Citation information

Title: ‘The Paris Commune’‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/paris-commune/

Date published: October 2, 2019

Date updated: November 9, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.