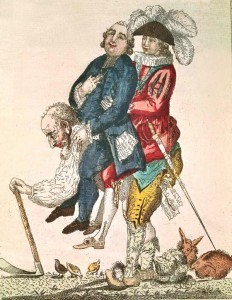

Who was responsible for the French Revolution? Ask this question of someone with a rudimentary understanding of history and chances are they would name the king, Louis XVI (1754-1793). Like many other monarchs on the eve of revolution, Louis and his wife Marie Antoinette have shouldered much of the blame for the suffering and unrest in their country. The French king has been variously portrayed as weak and vacillating, dishonest and careless, politically apathetic, indifferent to the needs of the French people, under the spell of corrupt ministers and under the thumb of his domineering wife. While there is no doubt that Louis’ leadership and political judgement were lacking, it is simplistic and unfair to attribute the revolution to his errors alone. The king was no intellectual or visionary but nor was he reckless or stupid. In a more settled age, he might have made a capable old regime ruler. With better judgement, he might have overseen France’s transition to constitutional monarchy. Instead, Louis found himself in a situation if not beyond his control then certainly beyond his understanding.

The future Louis XVI was born at Versailles in August 1754. He was the second son of Louis, Dauphin of France, and his German-born wife Maria Josepha. At the time of his birth, Louis was third in line to the throne, behind his father and older brother. Because of this, the young prince was sidelined and not trained for royal duties. Louis was a strong student nevertheless, excelling in history and languages. An avid hunter like his grandfather Louis XV, the prince also studied locksmithing as a useful hobby. His life changed in the 1760s, when tuberculosis claimed his older brother (1761) and his father (1765), leaving the 10-year-old prince as heir to the Bourbon throne. Five years later Louis entered into an arranged marriage with Marie Antoinette, a 14-year-old Austrian princess. The union was orchestrated by his grandfather, Louis XV, and the bride’s powerful mother, Maria Theresa, to secure a lasting alliance between France and Austria. Louis and Antoinette’s first fumbling attempts at love-making were disastrous, due to the young prince suffering an extended foreskin that made erections painful and sexual intercourse almost impossible. Louis underwent surgery to correct this problem but Antoinette did not conceive a child until eight years after their marriage.

In May 1774 Louis XV died and his grandson ascended to the throne, aged 19. The young Louis XVI was moderately intelligent, aware of his royal responsibilities and alert to the need for strong leadership – but he proved a mediocre king, relying excessively on his advisors and showing insufficient interest in the business of state. Louis preferred his regular leisure pursuits to reading dispatches, consulting ministers or considering policy. He was also a strongly religious man who worshipped daily and sought the counsel of higher clergy, both on personal affairs and matters of government. Shortly after taking the throne Louis followed ministerial and aristocratic advice and restored the power of the parlements, the high courts whose power was abolished by Louis XV after their blocked his legislative reforms. This confrontation would be repeated during his grandson’s reign.

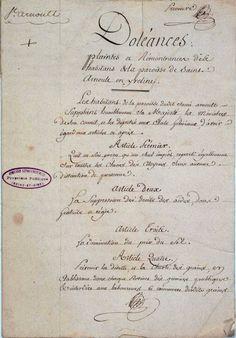

The French Revolution was precipitated by a financial crisis. Louis XVI ruled one of the world’s most powerful empires – but he also governed a nation choked by debt, fiscal mismanagement and a corrupt and inequitable system of taxation. Competent ministers gave the king sound advice on how to correct France’s financial woes. He wisely accepted much of this advice, however, attempts at reform were blocked by obstinate nobles in the parlements and the Assembly of Notables. In 1788, the financial crisis became a political crisis when the king was wrestled into summoning an Estates General, France’s closest equivalent to a national parliament. Neither Louis or his ministers foresaw the political challenges that lay ahead. The king initiated the Estates General in May 1789, hoping to push through some fiscal reforms – but the delegates representing the Third Estate had other plans, invoking a confrontation over voting rights, representation and national power. A month into the Estates General, the king lost his eldest son to tuberculosis. Within another month, he had surrendered his absolutism to the newly-formed National Assembly.

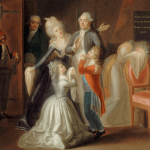

From this point, the fate of Louis XVI was inextricably tied to the events of the revolution. The king might have retained both his throne and his life had he understood the revolution, accepted its inevitability and showed appropriate judgement. Instead, he clung to a misguided hope that the changes wrought by the revolution could be minimised or even reversed. As the revolution progressed, Louis slipped from political leader to political prisoner. In October 1789, a violent mob assailed the royal family at Versailles and forced the king to relocate to Paris. He promised loyalty to the new state and its constitution, however, the revolutionary government’s attacks on the church and émigré nobles alienated the king, who believed that things had gone too far. In June 1791 Louis and his family all but abandoned the new regime by attempting to flee Paris. They got as far as Varennes, where they were arrested and turned back to the capital under guard. Moderate politicians tried to recover the king’s position but his treachery had driven the ordinary people of Paris into a Republican frenzy.

“It is easy to see how historians have been able to turn this really very average man into a hero, an incompetent, a martyr or a culprit: this honourable king, with his simple nature, ill adapted for the role he had to assume and the history which awaited him… Where personal qualities were concerned, Louis XVI was not the ideal monarch to personify the twilight of royalty in the history of France: he was too serious, too faithful to his duties, too thrifty, too chaste and, in his final hour, too courageous.”

François Furet, historian

The last act of Louis’ reign began in August 1792, when a Paris mob swarmed into his palace at the Tuileries, slaughtering soldiers and forcing the king to take refuge in the Legislative Assembly. Under siege from the people, the Assembly had no alternative but to suspend the king and dissolve itself. The government passed to a National Convention, which abandoned the 1791 constitution, abolished the monarchy and initiated a French republic. As for the former king, he spent his last weeks in the Temple, a fortress in the northern suburbs of Paris, while deputies in the Convention debated his fate. By late 1792 they had resolved to put the king on trial, not before an independent court but before the Convention itself. It was an extraordinary move of questionable legality – but there was no avenue to review or challenge it. Louis’ trial began in December and lasted five weeks. The former king and his lawyers mounted a staunch defence to the charges levied by the Convention – but the guilty verdict was probably a foregone conclusion. Louis Capet, as he was known by then, was found guilty on January 17th 1793 and executed four days later. Contemporary reports suggest he went to his death bravely – but bravery, unlike good judgement, was never a quality that Louis lacked in life.

1. Louis XVI was the king of France from May 1774 until his execution in January 1793. The French Revolution unfolded under his rule and eventually toppled him from power.

2. At birth, Louis was third in line to the French throne. He became heir after the deaths of his father and older brother. In 1770 he married the Austrian princess Marie Antoinette, an arranged marriage for political purposes.

3. The Dauphin became King Louis XVI in 1774, aged 19. Though intelligent and prepared to accept advice, he proved a rather mediocre king, showing little interest in policy, detail or statesmanship.

4. The inability of Louis and his ministers to push through fiscal reforms in 1788 led to the king agreeing to convoke the Estates General, which in turn precipitated a challenge to his absolute political power.

5. From 1789 the king’s fate was determined by the events of the revolution. He ended up a virtual prisoner in Paris, and his June 1791 attempt to escape the city spelt the end of the constitutional monarchy. The king was removed from power in August 1792, sent for trial in December and executed in January 1793.

Historian Hilaire Belloc on Louis XVI’s character and personality (1911)

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn and S. Thompson, “Louis XVI”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/louis-xvi/.