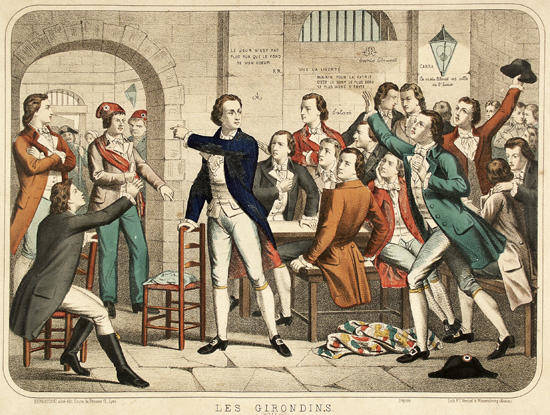

The Girondins and Montagnards were two powerful factions in the National Convention from its creation in September 1792 until the middle of the following year. These factions symbolised the competing perspectives of the French Revolution during this period. Girondin deputies were moderates with a national view while the Montagnards were radicals dominated by Parisian interests. Eventually, the tension between the two groups turned to conflict, leaving one victorious and the other expelled from the Convention.

Summary

Like politicians everywhere, France’s revolutionary legislators held different views on ideology, class, economics, provincial issues and other issues. This diversity was evident in the revolution’s first legislature, the National Constituent Assembly, where most radical deputies sat to the left of the president’s chair and moderate and conservative deputies sat to the right (a practice that gave rise to the modern terms “left-wing” and “right-wing”).

Similar alignments continued in the Legislative Assembly (October 1791-September 1792). Its replacement body, the National Convention, developed two distinct factions called the Girondins and the Montagnards. While these groups lacked the formal organisation and discipline of political parties, they were unified enough to vote in blocs and spend months disagreeing over policy.

This bickering came to a head in early June 1793 when the Montagnards, under pressure from the National Guard and the sans-culottes of Paris, expelled Girondin deputies from the Convention. Most Girondins were arrested or forced into exile. Of those who remained, few would survive the Reign of Terror.

Evolution of the Girdonins

The Girondinist faction took shape in the Legislative Assembly in the second half of 1791. It grew around the figure of Jacques-Pierre Brissot, a Republican lawyer and influential speaker in the Jacobin club. Brissot was a popular figure and a number of like-minded deputies gravitated toward him.

This faction became known as the Brissotins or Girondins, so named because many members were from Bordeaux in the Girdone département. Their numbers in the Assembly grew and their leaders and policies also came to attract many supporters outside it. High profile Girondins included economist and businessman Jean-Marie Roland and his salonnière wife Madame Roland, noted politician and philosopher the Marquis de Condorcet, future Paris mayor Jérôme Pétion, radical journalist Nicolas de Bonneville and the powerful orator Pierre Vergniaud.

Prominent Girondins not only shared the benches in the Legislative Assembly and National Convention, they also met regularly at Roland’s home and other residences to discuss events in the Convention, politics and strategy.

“In the [National] Constituent Assembly, Girondins and Montagnards were indistinguishable. The Legislative Assembly was a period of gestation. Embryos of the two ‘parties’ formed in late 1791 and early 1792, in debates over peace or war, and were born after painful labour during the seven weeks following August 10th 1792. It was then the Montagnards took control of the Paris Commune and Jacobins. The Montagnards also had the support of the Paris sections (electoral district assemblies) but their reliance on the sections meant they had to cosy up to radical agitators. Montagnards dominated the delegation elected by Paris to the Convention.”

Michael Kennedy, historian

Girondinist positions

At their peak, the Girondins had about 200 deputies in the National Convention. Leadership and policy-making were provided by a clique of prominent deputies dubbed the ‘inner sixty’. By late 1792, the Girondinist faction was most commonly perceived as being intellectual, measured, cautious and faithful to the revolution.

Politically, the Girondins were moderate Republicans. They initiated a revolutionary war in April 1792, hoping to pre-empt foreign aggression, win public support, militarise the revolution and export it beyond the walls of Paris. Their ideal society was free, capitalist and meritocratic with personal liberty protected by the rule of law.

Most significantly, the Girondins wanted a national government chosen by all citizens and representative of all citizens – not just the people of Paris. They distrusted the radicalism of Paris and believed the sections, the Commune and the em>sans-culottes exerted too much political influence. According to Brissot, these groups were “disorganisers who want everything levelled”.

Le Montagne

The Montagnards were not clearly recognisable as a faction until the National Convention. The terms Montagnards (‘mountain people’) or La Montagne (‘The Mountain’) were first used during sessions of the Legislative Assembly but were not in common use until 1793.

The Montagnards referred to those who occupied the higher benches in both the Jacobin club and the national legislature. Those who sat on these high benches were generally more radical in their ideology and their policies, while those who sat further down were usually more moderate.

Unlike the Girondins, who enjoyed considerable support in the provinces, the Montagnards drew much of their support from Paris. Of the 24 Parisian deputies in the National Convention, 21 sat with the Montagnard faction.

The Plain

The National Convention also contained a third grouping. Known as Le Plaine (‘The Plain’) or Le Marais (‘The Marsh’ or ‘The Swamp’), this mass of deputies occupied the floor space and lower benches of the Convention.

The Plain enjoyed an absolute majority in the Convention, boasting 389 of its 749 deputies in 1792. Because of this, no legislation or resolution could pass the Convention without the support of their deputies. Unlike the Montagnards and Girondinists, however, the Plain was filled with shiftless and uncommitted voters. Its deputies were effectively swinging voters, not wedded to a particular ideology or outlook. The best way to win the support of the Plain was with convincing oratory. This made speech-making a critical skill in the National Convention.

The Plain was generally moderate in the first months of the Convention, siding with the Girondins on most issues. As the revolution progressed and radicalised in 1793, many Plain deputies began to vote with the Montagnards.

Conflict intensifies

The conflict between the Girondins and Montagnards came to a head in the spring of 1793. The catalyst for this was the trial and guillotining of Louis XVI.

In January 1793, the National Convention found the king guilty and voted for his execution. Many Girondin deputies, fearing the king had been judged by Paris rather than the nation as a whole, sought an appel au peuple (‘appeal to the people’) – in effect, a referendum on whether the king should die. This motion was defeated in the Convention, which helped undermine Girondin authority. Among the Montagnards and the Jacobins, the Girondin appel au peuple was denounced as a royalist plot to save the king’s life.

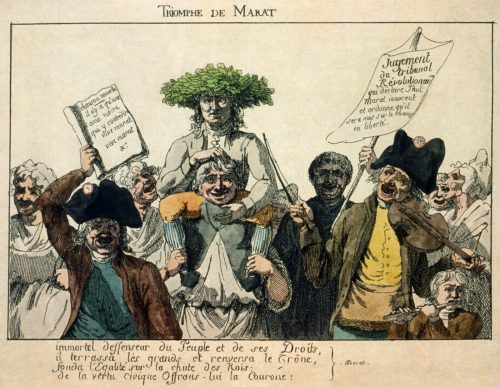

In April 1793, the Girondins fought back against Parisian radicalism, orchestrating the arrest of Jean-Paul Marat, a provocative street journalist turned Montagnard deputy. The following month they established the Commission of Twelve, a special committee tasked with investigating members of the Paris Commune and their alleged attempts to undermine the National Convention. After a brief investigation, the Commission ordered the arrest of several more radicals, including Jacques Hébert.

Calls for a Girondin purge

Having picked a fight with Parisian radicals, the Girondins now faced even greater opposition. The Commune, the Paris sections, the Jacobin club and the sans-culottes all denounced the Girondins as Royalists and Federalists (by this stage, both were anti-revolutionary slurs). Calls soon emerged to remove leading Girondins – or even all Girdondin deputies – from the National Convention.

On May 28th, a gathering of around 500 Parisian officials received several petitions and speeches, calling for an insurrection until the National Convention was purged of Girondins. Three days later, on the afternoon of May 31st, a number of protesters entered the Convention building and made demands of a similar nature. This drew supportive speeches from Montagnard deputies but little else.

On June 2nd, around 20,000 Parisians and a contingent of radical National Guardsmen gathered outside the Convention and demanded the expulsion of its Girondinist members. When the Convention president sent a message of protest against this intimidation, National Guard commander François Hanriot replied “Tell your fucking president that he and his Convention can go fuck themselves. If within one hour the 22 [Girondinist deputies] are not delivered, we will blow them all up.”

The radicals triumph

Surrounded and intimidated, the Convention dithered about what to do. Then, Montagnard radicals began to mount the tribune to argue for the expulsion of the Girondin deputies.

Leading this chorus was the wheelchair-bound Georges Couthon, who urged the Convention to abide by the will of the people. The National Guard was not holding the assembly to ransom, Couthon argued; they were its friends and wanted the Convention to choose wisely.

Jean-Paul Marat called for the Girondins to be arrested and detained. Bertrand Barère asked the Girondin deputies to prevent trouble by voluntarily resigning. The prominent Girondin Maximin Isnard refused to do so, declaring that he represented the people of his département and would resign only on their instruction.

Finally, after a standoff and debates lasting several hours, the Convention voted to expel the Girondins. The Girondinist faction had led the revolution since late 1791 – now it had been declared an enemy of the revolution. Some of the Girondin deputies were detained under house arrest. Others fled Paris to the provinces, where they tried to mobilise opposition against the Montagnard-dominated Convention.

In late October 1793, Brissot and 21 of his Girondin followers were tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal and guillotined.

1. The Girondins and Montagnards were two political factions that emerged during the Legislative Assembly and later dominated the National Convention.

2. The Girondins began as followers of the Jacobin orator Jacques Brissot. They were moderate Republicans who supported a revolutionary war and believed the revolution should involve the whole nation, not just Paris.

3. The Montagnards, in contrast, were more influenced by the people of Paris, particularly the sections and the sans-culottes. Their leaders included radicals like Robespierre, Marat, Couthon and Barère.

4. The Girondins and Montagnards frequently differed and bickered over policy. By the spring of 1793, this had developed into a factional war, the Girondins initiating action against radical agitators in Paris.

5. In early June 1793, the Montagnards emerged victorious after the Convention, surrounded by hostile soldiers and sans-culottes, was intimidated into expelling its Girondinist deputies.

Citation information

Title: ‘The Girondins and Montagnards’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/girondins-and-montagnards/

Date published: September 14, 2019

Date updated: November 5, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.