The swearing of the Tennis Court Oath (French, Serment du jeu de Paume) was a pivotal moment in the French Revolution. It took place in a royal tennis court at Versailles some six weeks into the Estates General. There, more than 500 members of the Third Estate and a scattering of liberal nobles and clergymen swore a solemn pledge to bind together and keep meeting as a National Assembly until France had its own constitution capable of achieving “the true principles of monarchy” and “the regeneration of public order”.

Summary

On June 17th 1789, members of the Third Estate, joining by a few liberal allies from the other Estates, began calling themselves the ‘National Assembly. On the morning of June 20th, this group gathered to enter the meeting hall at the Hôtel des Menus-Plaisirs, only to find the doors locked and guarded by royal troops.

Interpreting this as a hostile move by King Louis XVI and his ministers, the National Assembly proceeded to the nearest available space, one of Versailles’ indoor tennis courts. Gathering on the floor of this court, the 577 deputies took an oath, hastily written by Emmanuel Sieyès and administered by Jean-Sylvain Bailly. Together, they pledged to remain assembled until a new national constitution had been drafted and implemented.

Like the fall of the Bastille a fortnight later, the Tennis Court Oath was soon etched into history as a memorable gesture of revolutionary defiance against the old regime. The prominent artist Jacques-Louis David later immortalised the oath in a dramatic portrait.

Background

The Tennis Court Oath followed several days of tension and confrontation at the Estates General. Frustrated by the procedures of the Estates General, particularly the procedure of voting by order, the Third Estate spent the first week of June contemplating what action to take.

On June 10th, Sieyès rose before the Third Estate deputies and proposed inviting deputies from the other Estates to form a representative assembly. This occurred on June 17th when deputies of the Third Estate, along with several nobles and clergymen, voted 490-90 to form the National Assembly.

This was a clear challenge to royal authority – nevertheless, it took several days for the king to respond. Following the advice of Jacques Necker, Louis scheduled a séance royale (‘royal session’) involving all three Estates on June 23rd. There, the king planned to unveil reforms aimed at winning the support of moderates who he believed held the numbers in the Third Estate.

The oath is taken

The king’s plans to win over the Third Estate were thwarted by the events of June 20th and the swearing of the Tennis Court Oath.

Historians have long mused over why the doors of the Menus-Plaisirs were locked. Some have suggested it was a deliberate royal tactic, an attempt to stop the Estates meeting before the séance royale. It was more likely to have accidental, a procedural order that assumed the Estates would not meet again until June 22nd (June 20th was a Saturday).

Whatever the reason, the Third Estate deputies interpreted the barred doors as a hostile act, an indicator of their suspicious mood. They left the Menus-Plaisirs and proceeded to the next open building, the Jeu de Paume, a real tennis court used by Louis XIV. The oath was administered by Jean-Sylvain Bailly and signed by 576 members of the Third Estate. There was one abstention: Joseph Martin d’Auch, the deputy from Castelnaudary, refused to sign the oath on the grounds that it insulted the king.

The full text of the oath read:

“The National Assembly, considering that it has been summoned to establish the constitution of the kingdom, to effect the regeneration of public order, and to maintain the true principles of monarchy; that nothing can prevent it from continuing its deliberations in whatever place it may be forced to establish itself; and, finally, that wheresoever its members are assembled, there is the National Assembly… It decrees that all members of this Assembly shall immediately take a solemn oath not to separate, and to reassemble wherever circumstances require, until the constitution of the kingdom is established and consolidated upon firm foundations; and that, the said oath taken, all members and each one individually shall ratify this steadfast resolution by signature.”

David’s famous portrait

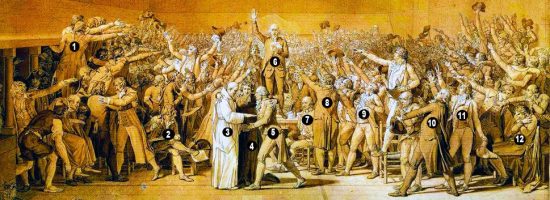

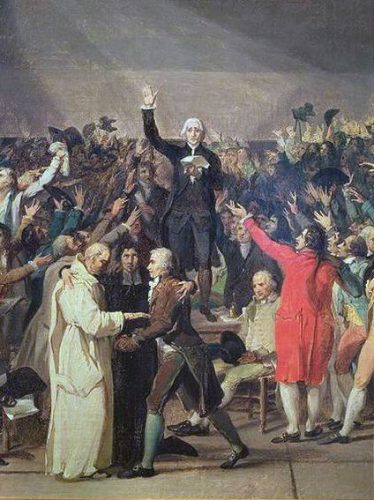

In 1790, the noted artist Jacques-Louis David began preparations for a grand painting to visualise and honour the swearing of the Tennis Court Oath.

While the events of the revolution prevented David from completing the painting, his preliminary engraving (above) survives and provides the best-known representation of the events of June 20th. The Tennis Court Oath was watched by people in the higher galleries; David consulted these witnesses when deciding on composition and placement.

Among the prominent revolutionaries shown in David’s engraving are Isaac Le Chapelier (1); the journalist Bertrand Barère (2); three religious leaders Dom Gerle (3), Henri Grégoire (4) and Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne (5); the famous astronomer and later mayor of Paris who administered the oath, Jean-Sylvain Bailly (6); the author of the oath Emmanuel Sieyès (7); the future mayor of Paris Jérôme Pétion (8); Maximilien Robespierre (9); the constitutional monarchists Honore Mirabeau (10) and Antoine Barnave (11); and the lone abstainer from the oath, Joseph Martin d’Auch (12).

“Jacques-Louis David recognised the gravity of the moment and the enthusiasm it released. He caught history in the making. Faces and bodies are frozen in an instant of the highest emotional intensity. The delegates are possessed by a common mission, which consists in preserving their newly won unity. The oath sworn in the tennis court outside the royal palace in Versailles… marks the beginning of the French Revolution. Language is at a loss as one tries to capture David’s visualisation of a unity manifesting itself as quantity.”

Stefan Jonsson, historian

The king responds

On June 22nd, two days after the Tennis Court Oath, the deputies of the Third Estate met at a Versailles church, together with 150 clergymen and two nobles. The king soon made an appearance and instructed those present to rejoin their Estates to continue their deliberations separately – but the leaders of the Third Estate refused.

When the séance royale opened the following day, Louis began by unveiling his reforms. The king promised a degree of representative government, with regular sessions of the Estates General. The taxation system would be overhauled in consultation with the Estates General, the legal system would be improved and lettres de cachet abolished.

While Louis was prepared to make political concessions and reforms, he would not accept constitutional changes. The Three Estates were an “ancient distinction” and an “integral part of the constitution”, the king declared, and would therefore remain intact.

Defiance continues

Had Louis XVI proposed these reforms in 1788 or earlier, they may well have averted the revolution and saved his throne. As the historian Richard Cobb puts it, the Tennis Court Oath had “cut the ground from under the king’s feet”.

By mid-1789, however, maintaining the Three Estates in their ancient form was unacceptable to the Third Estate, particularly if it continued to be outvoted by the other two Estates. Accepting the king’s reforms would also require the dissolution of the just-formed National Assembly.

When the séance royale ended and the king left the chamber, the deputies of the National Assembly defiantly remained. Stirred up by orators like Mirabeau, Bailly and Barnave, they affirmed the pledges made three days earlier in the Tennis Court Oath. The National Assembly would defy the king’s orders and remain in session. When confronted by one of the king’s envoys and asked to leave the hall, Mirabeau made his famous remark: “Go tell your masters who have sent you that we shall not leave, except by the force of bayonets”.

Death of the Estates

When the king was told of the National Assembly and their continued defiance, he responded with indifference, reportedly muttering “Fuck it, let them stay”.

Over the next three days dozens of clergymen and nobles, including the Duke of Orleans, a member of the royal court and a distant relative of the king, crossed the floor to join the National Assembly. On June 27th, the king backed down completely and ordered the remaining deputies of the First and Second Estates to join the National Assembly, thus giving it apparent constitutional legitimacy. The Tennis Court Oath, both a revolutionary act and an expression of popular sovereignty, had succeeded in forcing a royal backdown.

With one fell swoop, Louis XVI had abolished the Three Estates as separate political orders. Conservatives were furious about what the king had surrendered, however, when the news reached Paris it triggered great excitement and rejoicing. The bourgeois revolution, it seems, had won the day – but with large numbers of royal troops massing near Versailles and on the outskirts of Paris, there was still more confrontation to come.

1. The Tennis Court Oath was a pledge taken by Third Estate deputies to the Estates General. It was sworn in a Versailles tennis court on June 20th 1789.

2. After days of disputes over voting procedures, the king scheduled a séance royale for June 23rd. When the Third Estate gathered to meet on June 20th, they found the doors to their meeting hall locked and guarded.

3. Fearing a royalist conspiracy, the Third Estate responded by gathering in a nearby tennis court. There they pledged not to disband until the nation had drafted and implemented a constitution.

4. The Tennis Court Oath was written by Emmanuel Sieyès, administered by Jean-Sylvain Bailly and signed by 576 deputies with one abstainer. Later, the oath was famously depicted by the revolutionary artist Jacques-Louis David.

5. At the séance royale that followed, the king promised several major political and legal reforms but refused to disband the Three Estates. This led to further acts of defiance and, eventually, the absorption of the Estates into the National Assembly.

A record of the Tennis Court Oath (1789)

Citation information

Title: ‘The Tennis Court Oath’‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/tennis-court-oath/

Date published: October 31, 2019

Date updated: November 9, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.