The flight to Varennes is the name given to the royal family’s failed escape from Paris in June 1791. Dissatisfied with the course of the revolution, particularly its attacks on the Catholic church, King Louis XVI acceded to suggestions that it was time to flee the capital. Though well hatched, the plan failed and the royal family were arrested at Varennes, some 150 miles (240 kilometres) from Paris. Their capture was humiliating both for the king and the moderates who supported a constitutional monarchy, a system that now seemed unworkable.

Summary

By the spring of 1791, Louis XVI and his family had been under virtual house arrest at the Tuileries for more than 18 months. Appalled by the growing radicalism of the revolution, particularly its anti-clericalism, the king agreed to abscond from the city. The royal escape plan, hatched by Count Axel von Fersen and supported by Marie Antoinette, was to travel by coach to Montmedy, a fortress near the border with Germany that was garrisoned by royalist troops.

Despite a series of blunders, the royal entourage travelled to within 30 kilometres of its goal, before the king was recognised by a local postmaster. Louis and his family were promptly detained and hustled back to Paris under guard.

The flight to Varennes, though minor in itself, signed the death warrant for bourgeois dreams of a French constitutional monarchy. The king had attempted to flee the revolution and could no longer be trusted. His working alliance with the National Constituent Assembly and his acceptance of the Constitution of 1791 were exposed as fraudulent.

The role of Mirabeau

A number of factors caused Louis XVI to lose whatever faith he had in the revolution. One was the advice of Honore Mirabeau. At the Estates General two years earlier, Mirabeau had seemed an arch-radical, defiantly proclaiming that the National Assembly would only disperse at the point of bayonets.

Mirabeau’s own political vision for France, however, was fundamentally conservative. He favoured a strong monarchy with some of the king’s arbitrary powers checked by a constitution and a legislative assembly. If the monarchy fell, Mirabeau believed, the revolution would collapse into leaderless anarchy. Stripping the king of his powers would alienate him from the revolution and lead it to failure.

To avoid this, Mirabeau became a virtual double agent. In May 1790, he signed a secret deal with the crown, agreeing to work for the king’s benefit in the National Constituent Assembly. Mirabeau’s advisory notes to the king, discovered after his death in April 1791, paint a comprehensive picture of his actions.

By early 1791, Mirabeau was advising Louis to relocate to Rouen or some other provincial capital; once there he could rally support, appeal to the people and lead a national revolution, free of the dark influences in Paris. While he distrusted Mirabeau, the king seemed to accept his advice about retreating from Paris.

Religious motives

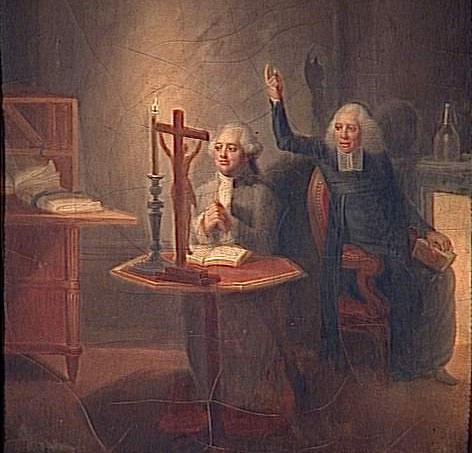

Another factor in Louis’ decision to flee Paris was his devout religious faith. The king was appalled by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and its implications for the church in France.

The Assembly had passed the Civil Constitution in July 1790 but Louis delayed signing it until December, hoping for a public outcry or an intercession from the Vatican. Privately, the king refused to attend any Mass given by a constitutional priest, believing this might endanger his immortal soul. Instead, he regularly attended Mass at a small chapel in the Louvre, given by refractory or non-juring priests.

A minor controversy arose in April when the king learned he would be expected to attend a public Easter Mass at Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois, also at the Louvre. This would mean receiving communion from a constitutional priest.

Seeking to avoid this, the king and his family planned to leave Paris on April 18th and spend Easter at their summer house at Saint-Cloud. They were prevented from leaving the Tuileries by a hostile mob, which trapped their carriage in a courtyard for two hours, hurling insults and projectiles. This incident only confirmed what most already suspected: the king and his family were virtual prisoners in Paris.

Fersen’s escape plan

The plan to flee Paris in June 1791 was concocted chiefly by Alex von Fersen, a Swedish aristocrat, military leader and diplomat. Fersen, a regular visitor to France from the late 1770s, had become a favourite of Marie Antoinette. It is often said that Fersen and the queen were lovers, however, evidence for this is circumstantial. What is more certain is that Fersen was operating with the financial backing of Sweden’s Gustav III, who wanted the French royal family to escape the dangers of Paris.

In May 1791, Fersen devised a complicated escape plan that involved leaving the Tuileries through unguarded doors, changes of clothing, false passports, bodyguards, a taxi carriage through the backstreets of Paris and an exchange of carriages on the city’s outskirts. Outside Paris, the king and his family would meet a platoon of Hussars and make their way to Montmedy, a fortress in north-eastern France manned by loyal soldiers.

The distance between Paris and Montmedy was around 200 miles (325 kilometres). Even at full speed, such a journey would take an entire day and require around 20 stops for fresh horses.

“The flight to Varennes opened up the second great schism of the revolution. There had been hardly any republicanism in 1789, and what there had been abated once the king was back in Paris and accepting all the Assembly sent to him. But after Varennes, the mistrust built up by his long record of apparent ambivalence burst out into widespread demands from the populace of the capital and a number of radical publicists for the king to be dethroned.”

William Doyle, historian

The plan goes awry

Fersen’s scheme proceeded as planned on the evening of June 20th, however, it was beset by a number of problems and delays. The king’s escape was delayed by a nighttime visit from the Marquis de Lafayette and Jean-Sylvain Bailly, who kept him talking longer than expected.

Marie Antoinette left the Tuileries as planned but spent several minutes wandering lost in the streets outside, before eventually locating her carriage. The king’s entourage eventually left but was forced to take a longer route out of Paris than originally planned. It was further delayed near the city gates by a wedding party.

All these delays put then at least 90 minutes behind schedule. Another hour was lost near Châlons, when the king’s carriage fell and damaged its harness sometime around dawn on June 21st. By this stage, the escape party was some four hours behind schedule – but with around half the journey to Montmedy completed, the royals were confident their plan would succeed.

The escape is discovered

Back in Paris, the king’s escape was discovered around the time he was passing Châlons. A contingent of National Guard was immediately dispatched in pursuit of the royal family.

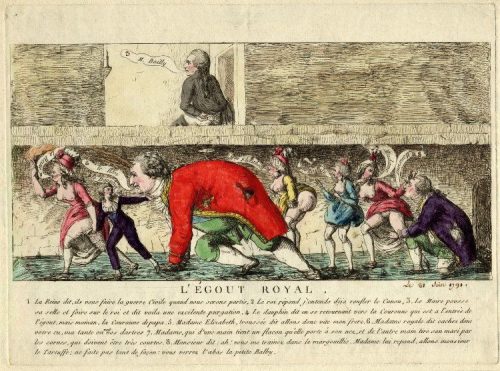

Word of the royal flight quickly spread around the city, prompting an angry reaction. Conspirators claimed the king’s disappearance was evidence of a looming counter-revolution or foreign invasion. Some accused high ranking city officials, including Bailly and Lafayette, of assisting the royal family to escape.

Meanwhile, the king’s coach proceeded on its journey and reached Sainte-Menehould, around 50 miles (80 kilometres) from Montmedy. While stopped there they were identified by the local postmaster, Jean-Baptiste Drouet who, according to legend, recognised the king from his portrait on a coin or assignat.

Arrest at Varennes

Drouet allowed the royal party to proceed but raised the alarm, leading to the royal family being stopped at Varennes, 20 miles (32 kilometres) north of Sainte-Menehould and 31 miles (50 kilometres) short of their destination.

The king was arrested at 11pm on June 21st and dispatched back to Paris at 7am the following morning. A large contingent of Royalist troops arrived as the king’s carriage was about to depart Varennes and contemplated an assault to rescue the king. Fearing the king and his family would be massacred, however, the Royalist officers refused to attack.

The king’s failed attempt to escape Paris was dubbed the flight to Varennes (something of a misnomer given the real objective of his flight was Montmedy).

Political ramifications

Whatever public affection the king had enjoyed in early 1791 was shattered by the events of June 20th and 21st. The royal family was returned to Paris and reinstalled at the Tuileries Palace, this time under more visible guard.

Their failed adventure triggered a rush of crude propaganda that ridiculed the royals and their fumbling escape attempt. The Paris sections and radical journalists demanded the immediate abolition of the monarchy and the creation of a republic. Some went further and insisted the king be put on trial for treason against the constitution.

Many were stunned not just by the king’s attempt to flee but how the National Constituent Assembly responded to it. Jerome Pétion, the Republican politician who later became mayor of Paris, was amazed at the reception afforded the king on his return to the city. His Majesty was treated, as Pétion noted, like nothing had happened:

“After a few minutes, we moved [to] the king’s apartments. Already all valets were in attendance, wearing their usual court dress. It seemed as if the king had merely returned from a hunting expedition, and everyone was assisting him with his toilet. In seeing the king, in observing him closely, it was impossible to guess that something momentous had just happened. He was so phlegmatic and tranquil, as if nothing was out of the ordinary. He immediately resumed his state of representation. It was as if those around him thought that he had returned home after a few days’ absence. I was perplexed by what I saw.”

The question of what to do with Louis XVI after Varennes widened the gulf between political moderates and radical republicans. The Constitution of 1791, which was in the throes of being finalised when the king absconded, was now a lame duck document. The king had spent two years mouthing support for the constitution but his actions in June 1791 had shown little but contempt for it.

Bourgeois dreams of a harmonious constitutional monarchy were shattered; the progress made since 1789 appeared to have been lost. Yet again, the new regime was faced with the challenge of reimaging and recreating the national government.

1. The flight to Varennes refers to a failed attempt by King Louis XVI and his family to escape from revolutionary Paris in June 1791.

2. Factors behind the king’s decision to flee included his lack of faith in the revolution and the Constitution of 1791, his personal religious beliefs, advice from Mirabeau and urging from his wife.

3. The escape was planned over the preceding month by Count Axel von Fersen, a Swedish general and favourite of Marie Antoinette, who planned to sneak the royal family out of Paris to the loyalist stronghold at Montmedy, in north-eastern France.

4. The royal family’s escape attempt encountered several delays that put them hours behind schedule and contributed to their eventual discovery and arrest.

5. The king and his family were arrested at Varennes and returned to Paris. While the National Assembly took no immediate action, radicals demanded the abolition of the monarchy and the formation of a republic.

Princess Marie-Thérèse’s account of the flight to Varennes (1791)

The note left by Louis XVI after fleeing Paris (1791)

Louis XVI explains his motives for the flight to Varennes (1791)

Marquis de Bouille explains his role in the flight to Varennes (1791)

The National Assembly responds to the flight to Varennes (1791)

Henri Grégoire on the flight to Varennes (1791)

Hébert on the flight to Varennes (1791)

Citation information

Title: ‘The flight to Varennes’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/flight-to-varennes/

Date published: September 20, 2019

Date updated: November 6, 2023

Date accessed: July 26, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.