The French Revolution began in the halls of Versailles but within a few weeks, Paris had become its beating heart. The French capital had increased rapidly in size during the 18th century, becoming one of the world’s largest cities. This brought with it attendant problems such as overcrowding, unemployment and urban squalor. In 1789, frustration over high food prices and political developments saw the people of Paris assemble to demand change. The Paris insurrection saw tensions between the royal government and its people reach a critical point.

The city of light

It is impossible to understand the revolution without knowing something of revolutionary Paris. By the late 1700s, Paris was a major city housing around 650,000 people. It was Europe’s second largest metropolis and the fifth largest city in the world after Beijing, London, Tokyo and Guangzhou (China).

Like other large cities, the French capital was filled with busy commerce, colour and diversity. Paris housed high society, operas, balls, universities, philosophes and busy salons. Its financial district and stock exchange handled the profits of France’s imperial and foreign trade. The artisans and workshops of Paris produced luxury goods that were stocked in the city’s swanky stores and shipped all around Europe.

As the historian David Garrioch puts it, “some found Paris beautiful, exceeding their expectation… unless the traveller was a blasé Londoner, the scale of Paris came as a shock even to those who had read about it”. By the late 18th century, Paris had acquired the nickname La Ville Lumière or ‘the city of light’, a reference to its culture and pivotal role in the Enlightenment.

Paris’ dark side

As impressive as it was, the French capital had its darker side. Behind the grand houses and buildings, Paris was also a city of squalid tenements, of roads awash with mud and filth, of air filled with cacophonous noises and gut-turning stinks.

By 1789, the French capital was desperately overcrowded, a consequence of the city’s rapid growth through the 18th century. Thousands of people poured into Paris during the 1700s, mostly former peasants who had abandoned the land in search of some kind of unskilled labour. In 1700, the population of Paris was scarcely half a million but by 80 years later, numbers in the capital had increased by almost 30 percent.

Most of Paris’ 650,000 souls ground out a desperate hand-to-mouth existence, relying on poorly paid work, hawking, scrounging, begging, crime and prostitution. Lower-class Parisians spent all of their meagre incomes paying for rent and food staples like bread, meat, oil and wine. Any rise in costs or prices was keenly felt.

The faubourgs

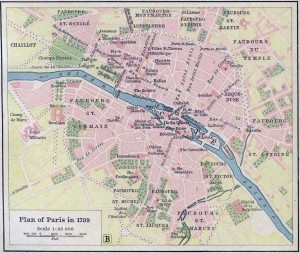

Just as London grew astride the River Thames, Paris was divided and defined by the Seine. This river flowed through the city centre in a north-east direction. Like most urban rivers of its era, the Seine was heavily polluted and ran thick with industrial waste, human sewage and animal effluent.

On both sides of the Seine, Paris was divided into a series of faubourgs (suburbs). The faubourgs on the southern or left bank of the Seine sat on higher ground that was less prone to flooding. These areas housed the city’s wealthier population. The Faubourg Saint-Germain, south-west of central Paris, straddled the road to Versailles and contained the city’s grandest, most opulent homes and châteaux. This quarter also contained Paris’ military infrastructure: the Hôtel des Invalides, the military college and the Champ de Mars parade ground.

The faubourgs directly south of the city housed its universities and colleges such as the Sorbonne. The majority of Paris’ industries and working class occupied the suburbs north and east of the Seine. The most unruly of these suburbs, the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, sat on the city’s eastern fringes, in the shadow of the Bastille fortress. Almost all of Paris was surrounded by a high wall, constructed both for defence and to stop goods moving into the city without the appropriate duties or taxes being levied.

Food prices and hunger

The insurrection that erupted in Paris in mid-1789 had four main causes: dire economic conditions, political developments at the Estates General and two critical decisions made by Louis XVI.

Harvests in 1788 had been very poor so Parisians had endured food shortages and high prices in the first months of 1789. In February 1789, city officials increased the official price of a four-pound bread loaf to 14.5 sous, an amount equal to 70 to 90 percent of the average daily wage. The royal government, alert to the dangers of an impending famine, moved to alleviate food shortages by sending finance minister Jacques Necker abroad to buy foreign grain and flour.

By the spring of 1789, hunger had pushed the people of Paris and other French cities to the verge of insurrection. In the three months between March and May, there were numerous reports of food riots, looting from bakeries and attacks on customs posts. It is no coincidence that the July 14th attack on the Bastille came on a day when bread prices, having eased through June and early July, returned to their peak of 14.5 sous per loaf.

“Since the end of 1788, Paris, in common with much of the rest of France, had been awash with fear, resentment and distress, caused mainly by the summer’s disastrous harvest and the glacial winter that followed… cries of “Death to the rich! Death to all aristocrats! Death to hoarders! Drown the fucking priests!’ rang through the streets, fanned by the widespread belief in the existence of an ‘aristocratic plot’. Conspiracy theories and scapegoating – two traditional components of the Parisian bread riot – were already taking on an explicitly political colouration. When news of Necker’s dismissal reached Paris, there was rioting in the Tuileries and at the Palais-Royal, where Desmoulins spoke wildly of an impending ‘Saint Bartholomew’s massacre of patriots.”

Richard D. Burton, historian

Fears of a counter-revolution

Amid this hunger and economic misery, Parisians keenly watched the unfolding changes at Versailles. The convocation of the Estates General, the drafting of the cahiers, disputes over voting by order and the formation of a National Assembly generated a measure of excitement and expectation among the working classes.

Political reform seemed imminent – many hoped it would bring economic relief in the form of lower taxes and the winding back of seigneurialism and aristocratic privilege. But some also feared a royalist reaction, an attempt by the king or royalist conservatives to resist change.

These fears seemed affirmed in the first week of July 1789 when royal troops were observed massing at Versailles, in northern Paris (Saint-Denis) and on the Champ de Mars. It is uncertain whether Louis XVI intended to order a full-scale counter-revolution (given the king’s later reluctance to deploy troops against the people, it seems unlikely) but the mobilisation of military divisions fuelled rumour and paranoia.

The journalist François-Noël Babeuf, later a radical Jacobin, arrived in the capital from northern France. He wrote to his wife and described the conspiracy theories that abounded in Paris:

“On my arrival in Paris, there was talk everywhere of a conspiracy led by the Count d’Artois [the king’s brother] and other aristocrats… A large number of the population of Paris would be killed, except those who submitted to the aristocrats and accepted the fate of slavery by offering their hands to the iron chains of the tyrants… If the Parisians had not discovered this plot in time, a terrible crime would have been committed. Instead, it was possible to form a response to this perfidious plan, which is unparalleled in all of history.”

The sacking of Necker

As Paris thrummed with rumours and speculation about the king’s intentions, Louis XVI made a fateful decision that seemed to confirm them. On July 11th the king, acting on the advice of conservatives in his court and probably also his wife, dismissed Jacques Necker from the ministry.

The sacking of Necker – who Parisians considered the most competent and reform-minded member of the royal cabinet – caused outrage in the capital. When news of the dismissal reached Paris on the morning of July 12th, several thousand people gathered at the Palais-Royal and listened to inflammatory speeches from Camille Desmoulins and others. It was a Sunday, ordinarily a day of rest and leisure, but Desmoulins urged them to close the theatres and take up arms against the government.

The crowd left the Palais-Royal around noon and began marching west, in the direction of the Tuileries and the Place de Louis XV. Some carried wax busts of Necker and the similarly popular Duke of Orleans, stolen from a local museum along the way. Contemporary accounts suggest the crowd, while noisy, was relatively peaceful. Few carried weapons and there were many women and children among its ranks.

Confrontation at the Tuileries

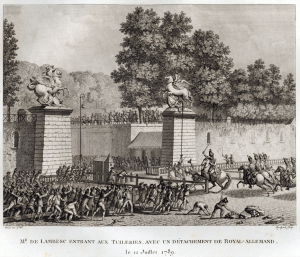

By mid-afternoon, the crowd had encountered and clashed with a small group of soldiers, pelting them with stones and rubbish. As the mob entered the Place de Louis XV and the Tuileries garden, they began to skirmish with cavalrymen commanded by Charles, Prince of Lambesc.

Accounts of what happened at the Tuileries vary wildly. According to revolutionary propaganda, both written and visual, Lambesc assembled his dragoons at the top of the Champs-Élysées and, with sword drawn, ordered his men to advance on the people below. This order to charge on unarmed civilians, wrote some, was the trigger point for insurrection in Paris. Royalist reports, in contrast, suggest that Lambesc acted appropriately to stop the crowd, which had planned to march on the military college, seize its weapons and take over the city. Other reports suggest there was no cavalry charge at all.

Reliable reports of deaths or injuries in the Tuileries incident are difficult to come by. At least one man was killed, an elderly marcher knocked over by a horse, though there may have been other fatalities.

The insurrection spreads

The skirmish at the Tuileries sparked wild rumours that the king’s soldiers were imposing martial law in Paris. Groups of Parisians resolved to defend themselves. From the afternoon of July 12th to the morning of July 14th, mobs broke into gun stores, private homes and small armouries, seizing weapons and ammunition. Government customs posts were also attacked; 40 out of 54 posts were destroyed, their staff beaten or chased away.

The Gardes Françaises (‘French Guard’), the royal garrison in Paris, was called out to quell the disorder. The soldiers refused to open fire on civilians, however, and in some cases openly fraternised with protestors.

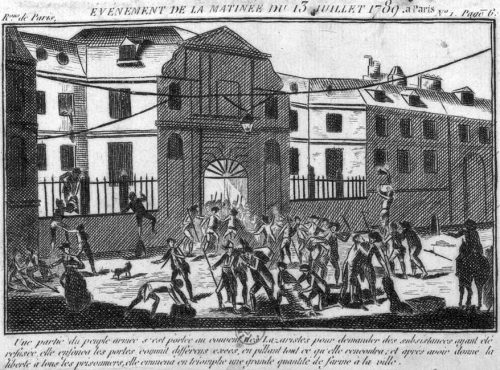

On the evening of July 12th, the electors of Paris met to discuss the situation in the city. They decided to remain in session until the crisis was over and to form a bourgeois militia to keep order (the origin of the National Guard). The following day, mobs ransacked the Invalides hospital and a monastery at Saint-Lazare, stealing guns and food respectively.

By midnight on July 13th, Paris was fully in a state of insurrection. What happened the next day would change the course of history.

1. The Paris insurrection describes unrest and anti-government violence that erupted in early July 1789 and culminated in the successful attack on the Bastille.

2. This insurrection had four causes: the desperate food situation in Paris, the political developments at the Estates General, the mobilisation of royal troops and the king’s dismissal of Jacques Necker from the ministry.

3. After Necker’s dismissal, the people of Paris assembled on July 12th and marched across the city, clashing with soldiers before being violently disbursed by Lambasc’s cavalry troops at the Tuileries.

4. Violence escalated through July 12th and 13th, as the people of Paris attacked government customs posts and invaded buildings in search of arms to defend the city.

5. By the evening of July 13th Paris was in a state of full insurrection. Many Parisians were armed and the city’s garrison, the French Guard, could not be relied on. The stage was set for the July 14th attack on the Bastille.

Madame de Stael recalls the sacking of Jacques Necker (1789)

Citation information

Title: ‘The Paris insurrection’‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/paris-insurrection/

Date published: October 10, 2019

Date updated: November 9, 2023

Date accessed: July 26, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.