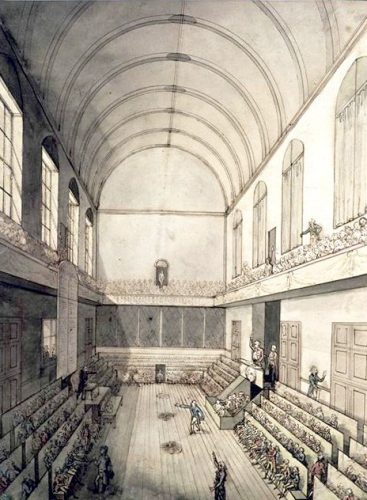

The Legislative Assembly was the governing body of France between October 1791 and September 1792, replacing the National Constituent Assembly. The Legislative Assembly inherited government at a time when there were grave doubts about the intentions of the king and the workability of the new constitution. It also had its own internal weaknesses, most notably a lack of political experience and questions about whether it was truly representative of the people.

A new legislature

The Legislative Assembly replaced the National Constituent Assembly, which had completed most of the work for which it was convened.

By September 1791, the deputies of the National Constituent Assembly had drafted a constitution they believed reflected the aims of the revolution. Feudalism, noble titles and the Ancien Régime’s other institutional inequalities had been abolished. The idealistic Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen had been adopted as a preamble to the new constitution. Royal absolutism was dead and the king stripped of most of his executive powers.

In late September 1791, Louis XVI gave his assent to the new constitution, pledging to “maintain it at home, defend it abroad and cause its execution by all the means at my disposal”. Its mission complete, the National Constituent Assembly voted for its own dissolution and handed government to the Legislative Assembly.

Optimistic views

To an outsider unaware of earlier events, this moment may have appeared the end of the French Revolution. France’s transition from absolutist monarchy to constitutional government seemed complete.

Consequently, some idealists viewed the handing of power to the Legislative Assembly with optimism, allowing the nation a fresh start from the rising tensions and violence of 1791. They believed the king had finally accepted constitutional change and hoped his earlier intransigence would be forgotten.

Writing at the time, the Marquis de Ferrieres suggested that “the king and queen appear entirely in favour of the constitution – and they are wise to do so… The people are delirious. The king and queen are acclaimed the moment they appear. So, you see, everything points to a solid new order of affairs.” Other Monarchiens (constitutional monarchists) expressed sentiments that were equally as hopeful.

Pessimism

Republicans and political realists had a dimmer view of the situation. They saw the Legislative Assembly as a body in charge of an unworkable political system – effectively, a lame duck legislature.

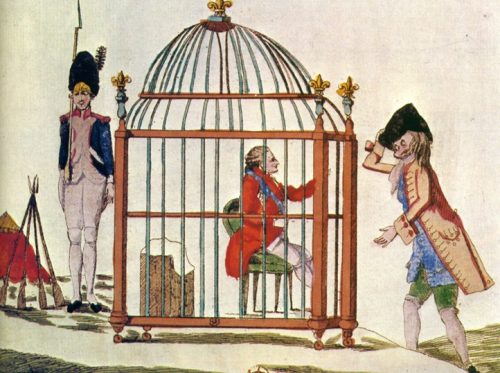

The constitution had been enacted but its head of state was a prisoner of the state after his failed attempt to flee Paris in June 1791. France was now a constitutional monarchy but its monarch was reluctant, untrustworthy and unpopular. The king, who was shiftless, uncertain and difficult to pin down on political questions, expressed little personal faith in the constitution.

In a conversation with the royalist politician Bertrand de Molleville, Louis XVI described the constitution as “far from a masterpiece”. “I think it has some great defects,” he told Molleville, “but I have sworn to maintain it, warts and all… Executing the Constitution in its literal terms is the best way of making the nation see the alterations that it needs.” This passage suggests the Legislative Assembly faced a king who was bent on constitutional sabotage.

A lack of representation

“The 745 deputies, newly elected by adult manhood suffrage, were pouring into Paris from all parts of France… There were no glittering personages here. Instead, they came with galoshes and umbrellas. They were largely seen as men of affairs and they had come to work. Few if any had great wealth and some had to make careful use of their allowance of 18 livres a day… There was still much work to be done by the Legislative Assembly, but the framework of the task was clear and its triumph was now beyond doubt. King and assembly were in harmony. The revolution was over.”

C. J. Mitchell, historian

To compound the problem of executive leadership, the new Legislative Assembly was itself neither politically experienced nor truly representative of the people of France.

The Assembly had been elected by ‘active citizens’ – that is, those affluent enough to pay a sizeable amount in taxation. Most working class citizens were not entitled to cast a vote for the new legislature. This exclusion outraged the radical sections and democrats in the Jacobin club, many of whom favoured universal suffrage.

The Legislative Assembly was also hampered by the self-denying ordinance, a regulation proposed by Maximilien Robespierre and passed by the National Constituent Assembly on May 16th 1791. The self-denying ordinance forbade all sitting members of the National Constituent Assembly from standing as candidates for the Legislative Assembly.

Robespierre’s ordinance was intended as an act of political self-sacrifice, to renew government and prevent an entrenchment of power in the new assembly. A small number of deputies opposed it, arguing that replacing the entire legislature would jeopardise the stability of the government.

Election and composition

Elections for the Legislative Assembly were held in September 1791. Most of the 745 deputies elected to the Legislative Assembly had a record in provincial or municipal government or the public service. Many were members of the Cercle Social and the Jacobin Club who had not won seats in the National Constituent Assembly.

That is not to say the Assembly was without men of talent or capability. Among those to take a seat in the Legislative Assembly were Jacques Brissot, the Marquis de Condorcet, the Republican lawyer Pierre Vergniaud, the Jacobin merchant Pierre Cambon and Georges Couthon, an ally of Robespierre.

Because the constitution kept ‘passive voters’ at arm’s length, the vast majority of deputies came from the middle classes. Almost half of them (330 deputies) were Republicans, while around one quarter (165) were Feuillant constitutional monarchists and the rest (250) were politically unaligned.

The Brissotin faction

In the first weeks of the Assembly, deputies gravitated around prominent leaders and developed into factions. The largest of these factions was led by the imposing figure of Jacques Brissot.

A lawyer turned political journalist, Brissot had acquired a reputation as a man of letters dedicated to the revolution. Before his election to the Legislative Assembly, Brissot sat in the Paris Commune and delivered several powerful speeches to the Jacobin club. He was also well travelled and had many contacts abroad, skills that prompted Brissot’s appointment to the Assembly’s diplomatic committee.

Brissot was considered a radical in 1789 when he occupied the centre-left of the Legislative Assembly. He was a moderate Republican who wanted to abolish the monarchy and the 1791 constitution. He was also in favour of war with France’s European neighbours: to bring about the collapse of the French monarchy, to export revolutionary ideas and to threaten monarchies elsewhere.

Brissot’s followers were variously known as the Brissotins, the Girondins (many hailed from the Gironde département) or the Rolandists (their leaders frequented the salon of Madame Roland).

Problems and challenges

During its short life, the Legislative Assembly was confronted with many problems and challenges. One of these was the constitutional authority of the recalcitrant king.

Louis XVI retained two significant powers that affected the functioning of the assembly: the power to appoint ministers and the power of suspensive veto. Louis appointed most of his ministers from the Feulliants or the centre-right, and many of these appointments were of dubious quality.

The king also created controversy and division by willingly using his veto to block the Assembly’s laws. In its first weeks, the Legislative Assembly drafted legislation to take action against émigrés and non-juring priests. It passed these laws on November 8th and November 29th respectively – but both were vetoed by the king. More royal vetoes followed in 1792 and each veto triggered a wave of public protest against the monarch.

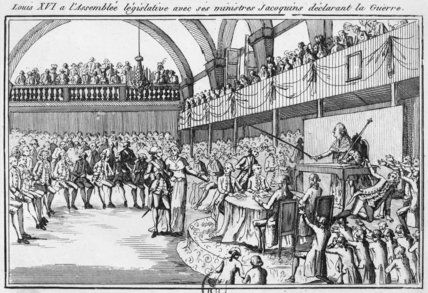

Declaration of war

The Legislative Assembly’s most significant measure was its declaration of revolutionary war against Austria (April 20th 1792). This was orchestrated by Brissot and the Girondins, who believed war would refocus the revolution, inflame French nationalism and consolidate their own power.

France’s revolutionary armies fared poorly in the first months of the war, however, and by summer 1792, an Austro-Prussian invasion seemed imminent. War would shape the mood in Paris, particularly after the Duke of Brunswick’s July manifesto that threatened to decimate the city.

Parisians were not intimidated and did not bow to his threats but the fear of foreign invasion and counter-revolution shaped events in the capital in July and August 1792. On August 10th the people of Paris rose in insurrection, replacing the city’s Commune and invading the king’s apartments at the Tuileries. The end result was the suspension of the king and the Constitution of 1791.

By instigating a war against other European powers, hastily and perhaps unnecessarily, the Legislative Assembly had contributed to its own demise.

1. The Legislative Assembly was the governing body of France between October 1791 and September 1792. It replaced the National Constituent Assembly.

2. The Legislative Assembly was formed under the Constitution of 1791, which created a constitutional monarchy with Louis XVI as the head of state.

3. The Assembly contained 745 deputies. Almost half were Jacobin republicans while the rest were Feuillants (constitutional monarchists) and political moderates.

4. The dominant faction in the Assembly was the Girondins, headed by Jacques Brissot. This faction led the push for war with Austria, which was eventually declared in April 1792.

5. The Legislative Assembly faced several challenges, including political inexperience and questions about both the king’s authority and its own, given its limited representation.

Citation information

Title: ‘The Legislative Assembly’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/legislative-assembly/

Date published: September 15, 2019

Date updated: November 10, 2023

Date accessed: July 26, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.