Political clubs were an important feature of the French Revolution from late 1789. Beginning as informal gatherings of like-minded political idealists in 1789, the political clubs gradually became more organised and ideologically driven, morphing into de facto political parties. The most prominent clubs included the Society of 1789, the Cordeliers and the Feuillants. The best known, however, was the Jacobin club, which became an important source of radicalism in 1791 and beyond.

Formation

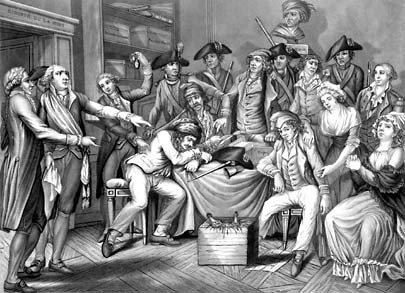

Most political clubs began as another politically oriented social event, not unlike the salons, circles and literary associations of the 1780s, with like-minded people gathering to discuss political matters.

The first political clubs were formed early in the revolution and were relatively informal. As the revolution progressed, however, they became more organised and formalised. Most developed their own customs, procedures and membership requirements; they acquired a regular meeting place and members attended there regularly, sometimes every night.

Some clubs behaved in a similar fashion to modern-day political parties. Their members reviewed the day’s developments, debated issues, set agendas, decided policy and formulated strategy for the future. Many deputies in the various national legislatures were also members of political clubs; their actions in government were often influenced by what transpired in the clubs. The most famous of all political clubs, the Jacobins, would shape the course of the revolution between 1792 and 1794.

The Breton Club

The French Revolution’s first significant political club was the Breton Club. It began as an informal gathering of 44 Third Estate deputies at a Versailles café, before and after sessions of the Estates General.

At first, most of the deputies who attended these interludes were from Brittany, hence the name of the club. Their meetings often discussed provincial issues as well as the proceedings at the Estates General. By early June, however, the Bretons had opened their meetings to deputies from other regions, as well as a few liberal aristocrats.

Breton Club meetings were attended by influential figures like Honore Mirabeau, Emmanuel Sieyès, Isaac Le Chapelier, Antoine Barnave and Maximilien Robespierre. Members of the Breton Club supported liberal political reforms including voting by head, the adoption of a constitution and the formation of a national assembly.

During the events of June 1789, the Breton Club was assembling more frequently and gathering before each session of the Estates General in order to discuss strategy.

The shift to Paris

Numbers at the Breton Club dwindled in July, following the formation of the National Assembly. Those members not from Brittany soon drifted away from the club, their mission apparently accomplished. By the time the Estates General was dissolved, the club was again in the hands of deputies from Brittany.

In early October 1789, following the march of Parisians on Versailles, Louis XVI and the National Constituent Assembly relocated to Paris.

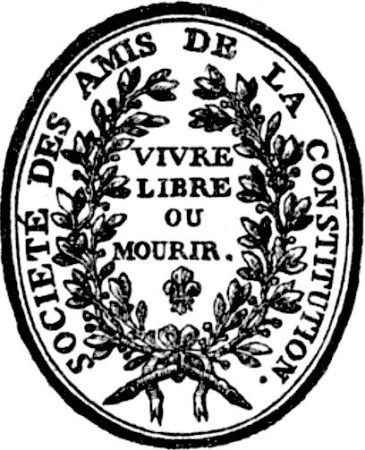

With the revolution now shifted to the capital, Breton Club deputies began assembling again here, meeting in a Dominican monastery on the Rue Saint-Honoré, not far from the Tuileries. They adopted the formal title Société des amis de la Constitution (‘Society of the Friends of the Constitution’). The popular press, however, scornfully referred to them as the Jacobins, a local colloquialism for Dominican monks.

The Jacobin club

Over the next few months, the Jacobins evolved and expanded their group. The club adopted a set of rules written by Antoine Barnave (February 1790) and a manifesto outlining the club’s purposes.

At first, membership of the Jacobin club was restricted to deputies in the Assembly. By the spring of 1790, dozens of individuals outside the legislature were being invited to join. Members had to be ‘active citizens’ and pay an annual fee of 24 livres, which confined Jacobin membership to the middle and upper classes. By May 1790, the club had around 1,500 members. In October, the Jacobins opened their meetings to members of the public, who were permitted to sit in the galleries and listen to speeches and debates.

Club meetings were held four times a week and followed a planned agenda, addressing constitutional issues and questions currently before the National Constituent Assembly. Through 1790 and early 1791 the Jacobins remained faithful to the constitution and constitutional monarchy, though a minority of its members harboured more radical political views.

“From the outset, the ideal Jacobin was a man of independence, courage and heroism, who stood firm against the egoist ‘vampires’ and ‘parasites’ of the aristocracy, and considered only the public good – in short, a man of virtue… Nine-tenths of the Jacobins were commoners but their leaders were from the social elite of the old regime… Most of these men had been members of the Society of Thirty and, later, the Breton Club. For many months they dominated Jacobin politics, exercising a near monopoly over the offices of president and secretaries for the Jacobins.”

Marisa Linton, historian

The Society of 1789

As the revolution progressed, new clubs emerged on the right of the political spectrum. In April 1790, a group of constitutional monarchists, frustrated by growing radicalism, abandoned the Jacobins to form their own group called the Society of 1789.

According to contemporary observers, the Society of 1789 numbered around 300 men, including 40 to 50 deputies from the National Constituent Assembly. Membership was exclusive and individual members were either politically powerful or independently rich. Among the more notable members of the Society of 1789 were the Marquis de Lafayette, Honore Mirabeau, Jean-Sylvain Bailly, Emmanuel Sieyès, the Marquis de Condorcet and Isaac Le Chapelier.

Meetings of the Society were not unlike social gatherings of the Parisian elite, with fine dining followed by brandy and wine, served on a balcony overlooking the Palais Royal. The Jacobins came to despise the Society of 1789, considering them a remnant of the privilege and elitism of the Ancien Régime.

The Cordeliers

Another group to emerge during this period was the Société des Amis des droits de l’homme et du citoyen (‘Society of the Friends of the Rights of Man and Citizen’). It began as a group of representatives from the Cordeliers district, an unruly working class area near the left bank of the River Seine. They began meeting in April 1790 and were quickly dubbed the Society of Cordeliers.

Politically, the Cordeliers were the most radical of the political clubs during 1790 and 1791. They were more populist than the Jacobins: membership was open to all and membership fees were kept low (one livre and four sous per annum).

Cordeliers’ meetings were chiefly concerned with grievances and criticisms. Their focus was on the protection of individual rights and freedoms; “Liberty, equality, fraternity” was the club’s slogan. They were sympathetic to working-class interests and were alert to abuses and corruption. The Cordeliers also maintained a watching brief on the draft constitution and expressed strong criticisms of its formation of ‘active’ and ‘passive’ citizens.

The role of clubs in 1791

The flight to Varennes and the king’s arrest and return to Paris had a profound effect on the political clubs of Paris.

Inside the Jacobin club, the king’s actions opened a rift between the Republicans and Monarchiens (constitutional monarchists). During the summer of 1791, the Monarchiens abandoned the Jacobins and established a new group called the Feuillants. They were joined there by members of the Society of 1789, which by this time had fallen away.

The Feuillants sought to create a Jacobin-style club to attract political moderates. Their aim was to provide an antidote to the growing republicanism and radicalism in Paris, and to influence developments in the National Constituent Assembly. But while the Feuillants were well represented inside the legislature, they failed to attract much support on the streets of Paris.

The remaining Jacobins also suffered from low numbers. By November 1791, their membership had halved to just 1,200. Their numbers recovered through 1792 as the club came under the influence of prominent Republicans like Jacques Brissot and Maximilien Robespierre.

1. Political clubs were groups of like-minded people who met socially, outside the legislatures and formal political bodies, to discuss and debate political issues and events.

2. These clubs began informally as social gatherings, however, they evolved over time, to the point where they functioned as de facto political parties, setting agendas and shaping decisions in the legislature.

3. The first of these groups was the Breton Club, which met at Versailles during the Estates General. After moving to Paris in late 1789 this group evolved into the Jacobin Club.

4. Other clubs active during the first years of the revolution included the Society of 1789 (aristocratic and wealthy constitutional monarchists) and the Cordeliers (a populist and democratic group based in working-class Paris).

5. The Jacobin Club remained moderate and supportive of a constitutional monarchy until the club split in July 1791. Its constitutional monarchists left to form the Feuillants, while those who remained fell under the influence of republicans like Brissot and Robespierre.

The National Assembly debates political clubs (September 1791)

Citation information

Title: ‘The political clubs’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/political-clubs/

Date published: September 12, 2019

Date updated: November 10, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.