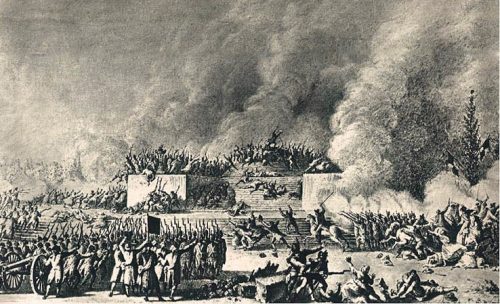

The Champ de Mars massacre occurred in Paris in July 1791. When republican political clubs called on people to assemble to petition for the abolition of the monarchy, the Paris Commune, fearing an insurrection, responded by calling out the National Guard. In the turmoil that followed, as many as 50 people were killed and dozens more wounded. The Champ de Mars massacre was a turning point in the new society. It shattered the reputations of moderate leaders, sparked a rise in political radicalism, facilitated a split in the Jacobin club and helped seal the fate of the king.

Responses to Varennes

The catalyst for the Champ de Mars incident was the royal family’s attempt to flee Paris in June 1791 and their subsequent arrest at Varennes. To many, the flight to Varennes exposed the king as untrustworthy and made the constitutional monarchy unworkable.

Many Parisians were also concerned by the actions of the National Constituent Assembly, which had attempted to paint the king’s flight as an abduction (the Assembly’s official statement was that Antoine Barnave and Jérôme Pétion had been sent to “rescue” the king, not arrest him). This political spin fooled few, particularly after the contents of the king’s farewell note to the Assembly were made public.

For the next three days, Paris thrummed with demands for the king to be put on trial and the declaration of a republic – or at the very least, a national referendum on the matter. On June 24th, around 30,000 Parisians marched on the Assembly’s chambers in the Tuileries, carrying a petition demanding a republic. When the royal family arrived back from Varennes the following day, crowds lined the streets in a menacing fashion.

The government’s plan

The government now faced a dilemma. Before the king’s arrest at Varennes, the Assembly was about to sign off on the Constitution of 1791, formalising France’s transition into a constitutional monarchy. The reigning monarch, through his attempt to flee, had effectively disowned the revolution and the constitution.

With few republicans on its benches, the Assembly chose to continue as if nothing had occurred. Moving to punish or depose the king would provoke Austria and Prussia, who were already threatening war against revolutionary France. With strikes and unrest growing, the Assembly also feared that removing the king and the monarchy – two symbols of national continuity and stability – would invite further destabilisation.

The Assembly planned to pass the new constitution and finish the revolution, not start it again. Redeeming the king and reinstalling him with limited political power seemed the safest option. These were sentiments echoed by Barnave, who on July 15th told the Assembly that “any change today would be fatal, any prolonging of the revolution today would be disastrous… It is time to bring the revolution to an end”.

The king restored

The same day as Barnave’s speech, the Assembly decreed that the king had been abducted and that his monarchy was inviolable, announcing his restoration to the throne. A supplementary decree suspended Louis from political duties until the constitution had been adopted and the king had personally sworn to honour and uphold it.

These decrees sparked outrage on the streets of Paris. Republicans dubbed the Assembly’s July 15th resolution “the Great Lie”. It drove a wedge through the centre of the Jacobin club, which for weeks had succumbed to factional bickering between its Monarchien leadership and a growing number of Republican members. According to Furet, “between the vote of July 15th and fusillade on the Champ de Mars on July 17th, a new Jacobinism was born”.

The Cordeliers, a more radical political club with an open door membership policy, drafted a petition that challenged the authority of the National Constituent Assembly:

“Legislators! You have allocated the powers of the nation you represent. You have invested Louis XVI with excessive authority. You have consecrated tyranny in establishing him as an irremovable, inviolable and hereditary king. You had sanctioned the enslavement of the French in declaring that France was a monarchy… But now, times have changed. The so-called convention between the people and their king no longer exists. Louis has abdicated the throne. From now on, Louis is nothing to us.”

The crowd assembles

The republican faction of the Jacobin club, which had grown in size and outspokenness since the flight to Varennes, issued a similar petition. The “outraged nation”, this petition warned, “cannot entrust its interests and the reins of its empire to a perfidious, traitorous fugitive”.

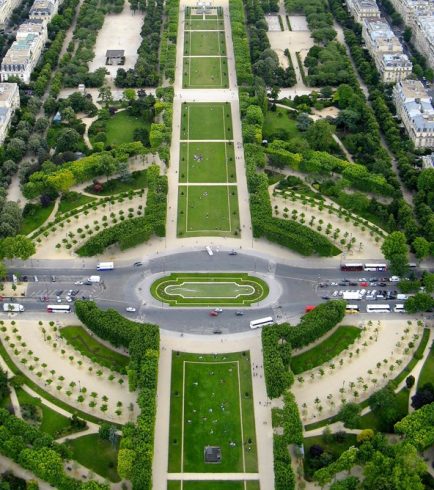

On the morning of Sunday July 17th, a crowd began to assemble on the Champ de Mars (‘Field of Mars’), a huge parade ground on the west of the south bank, where the Eiffel Tower now stands. The second Fête de la Fédération, an annual celebration of the storming of the Bastille and the achievements of the revolution, had been held there three days before.

Now, several thousand people were gathering on the Champ de Mars in defiance of the National Constituent Assembly, which had decreed that “no club or society could meet without a certificate”. Those assembled heard speeches from radical orators while around 6,000 people signed or put their mark to the Republican petitions.

Confrontation at Champ de Mars

The morning was punctuated by insults and scuffles between republican protestors, gendarmerie and members of the National Guard, but with no significant violence. By the afternoon, the crowd on the Champ de Mars had swelled significantly (conservative reports suggest it reached 25,000, some have claimed as many as 50,000).

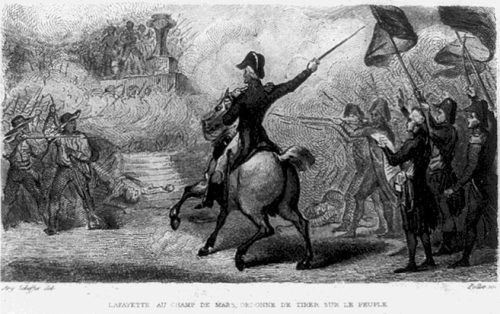

The mayor of Paris, Jean-Sylvain Bailly, received police reports suggesting the assembly at the Champ de Mars was relatively peaceful, however, an apparently unrelated incident – the lynching of some itinerants by a local gang – convinced the nervous Bailly to call out a battalion of the National Guard and declare martial law.

Bailly and Lafayette led the National Guard to the Champ de Mars late in the afternoon. On arrival, they were mobbed, insulted and, according to some reports, pelted with stones. This fracas became deadly when several National Guard soldiers opened fire. It is unclear if soldiers were ordered to fire and, if they were, who gave them. Within an hour between 30 and 50 people lay dead, while dozens more nursed gunshot and powder wounds.

“Even though the incident at the Champ de Mars may have united the patriot deputies, the violence unquestionably tarnished those who favoured the constitution. The killings and the wave of arrests that followed made a mockery of Barnave’s exhortation: to make France a nation in which all patriotic citizens could live in peace, irrespective of their opinions… The massacre at the Champ de Mars underscored the need to complete the constitution, for political life was frozen and, for the first time, an alternative course had arisen from outside the Assembly.”

Michael P. Fitzsimmons, historian

Effects of the violence

The deaths on the Champ de Mars caused a pivotal shift in the French Revolution. The National Constituent Assembly’s response to the Champ de Mars incident was to blame it on political radicals and the gutter press. Several newspapers were forcibly closed, some radical leaders were arrested and provocateurs like Jean-Paul Marat, Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins were forced into hiding.

The violence also caused an enduring split in the Jacobin club. Its constitutional monarchists abandoned the club to form the Feuillants, while those who remained were further radicalised.

The Champ de Mars incident also ended the unspoken between the people of Paris, the Commune and the National Guard. Whatever respect and affection Parisians still felt for Bailly and Lafayette had been shattered. Bailly, in particular, was condemned for his betrayal of the people, for calling out armed troops against civilians exercising their freedom to assemble.

The discredited Bailly later fled Paris but was spotted and arrested in late 1793, as the Reign of Terror was unfolding. At his trial, Bailly was accused of directing the Champ de Mars killings due to his “thirst for blood”. Found guilty in November 1793, Paris’ first mayor was guillotined on the Champ de Mars, an act of symbolic retribution.

1. The Champ de Mars Massacre refers to the killing of 30-50 Parisian civilians by soldiers of the National Guard at a political protest on July 17th 1791.

2. This incident was precipitated by the king’s flight to Varennes and the National Constituent Assembly’s response to it, which fuelled republican sentiment, protests and petitions in Paris.

3. This was particularly evident in the Cordeliers and Jacobin clubs, whose members drafted petitions calling for the deposition of the king and urged Parisians to sign these petitions on July 17th.

4. Fearing this gathering may turn insurrectionary, Paris mayor Jean-Sylvain Bailly called out the National Guard. Their arrival at the Champ de Mars led to a confrontation, gunfire, deaths and injuries.

5. The Champ de Mars Massacre increased radicalism in Paris, caused a split in the Jacobin club and caused many Parisians to lose faith in the Assembly and the Commune. It also shattered the reputations of Bailly and Lafayette.

Citation information

Title: ‘The Champ de Mars massacre’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/champ-de-mars-massacre/

Date published: September 3, 2019

Date updated: November 10, 2023

Date accessed: July 26, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.