The Cult of the Supreme Being, created in May 1794, was an ambitious attempt to construct a national religion based on patriotism, republican values and deism (the Enlightenment theory that God existed but did not interfere in the affairs of men). For its creator, Maximilien Robespierre, the Supreme Being movement was intended to educate and enlighten the people about the fundamental connections between religion, morality, republican government and citizenship. Few came to share this enthusiasm and the Cult of the Supreme Being lasted only as long as its benefactor, dying with Robespierre in July 1794.

The Cult of Reason

The Supreme Being movement was not the revolution’s first attempt to replace Catholicism. In 1793, radical journalist Jacques Hébert and his followers founded the Cult of Reason, a group dedicated to celebrating liberty, rationalism, empirical truth and other Enlightenment values.

The Cult of Reason was, in essence, an atheist church. It embraced the trappings and practices of religion, such as congregational services, symbolism and worship – but its advocates denied the existence of any deity or supernatural forces. The Cult of Reason became popular among intellectuals and sans-culottes alike.

From mid-1793, the Jacobin-dominated Convention gave tacit approval to the Cult of Reason. The culmination of the movement was the Festival of Reason, held in the Notre Dame cathedral on November 10th 1793.

Formation

The Cult of Reason’s atheism outraged the French Revolution’s arch puritan, Maximilien Robespierre. Robespierre was greatly concerned about public morality. France could never have a virtuous and effective government, he claimed, until the people themselves were taught morality and virtue.

Robespierre believed the revolutionary government must lead this process by engaging “in the art of enlightening them [the people] and making them better”. This could not be achieved with atheism, he thought, only through an inclusive cult that combined worship of the divine creator with patriotic ceremonies.

On 18 Floreal (May 7th), Robespierre rose in the Convention and delivered one of his most famous orations, speaking of the revolution, its achievements and the pivotal connection between virtue and terror. At Robespierre’s behest, the Convention passed a Decree on the Supreme Being (1794). This decree acknowledged the existence of a Supreme Being and legislated for its worship:

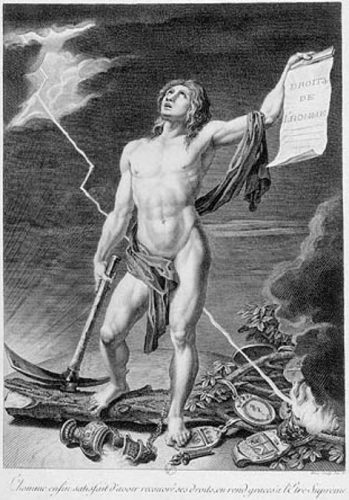

“1. The French people recognise the existence of the Supreme Being and the immortality of the soul.

2. They recognise that the worship worthy of the Supreme Being is the practice of the duties of man.

3. They place in the first rank of these duties [the obligation] to detest bad faith and tyranny, to punish tyrants and traitors, to rescue the unfortunate, to respect the weak, to defend the oppressed, [and] to do to others all the good that one can and not to be unjust toward anyone.

4. Festivals shall be established to remind man of the thought of the Divinity and of the dignity of his being.

5. They shall take their names from the glorious events of our revolution, from the virtues most dear and most useful to man and from the great benefactions of nature.

6. The French Republic shall celebrate every year the festivals of July 14th 1789, August 10th 1792, January 21st 1793, and May 31st 1793.

7. It shall celebrate on the days of decadi festivals to the Supreme Being and to nature, to the human race, to the French people, to the benefactors of humanity, to the martyrs of liberty, to liberty and equality, to the Republic….”

“A substantial section of the speech on 18 Floreal was devoted to a condemnation of atheism. This, Robespierre argued, dissolved the bonds of society. It led people to believe that the fate of all, good as well as wicked, was decided by blind chance. Society was left at the mercy of the strongest and the cleverest. By contrast, religion reinforced the social bonds by differentiating between the regenerate and the unregenerate. It is not altogether clear how Robespierre saw this working.”

Colin Haydon, historian

Robespierre’s motives

Many historians have pondered whether the Supreme Being was a genuine reflection of Robespierre’s personal religious beliefs, or a clever attempt to use religion to enhance his own power. It may have been both.

There is certainly evidence that Robespierre believed in God and the immortality of the soul. Like other Jacobins, he had been a barbed critic of the church, but his attacks were almost always confined to the higher clergy. Robespierre supported the Civil Constitution of the Clergy because it stripped the church of its economic privileges and removed prelates from political power but he had often defended parish priests and friars.

Robespierre’s Supreme Being was certainly not a direct replacement of the Catholic God. The Supreme Being was a deistic Enlightenment entity, a wise and rational God who had created the world and set it in motion according to natural laws. The best way to regenerate society and draw closer to this Supreme Being was to study, uphold and honour these natural laws.

Festival in Paris

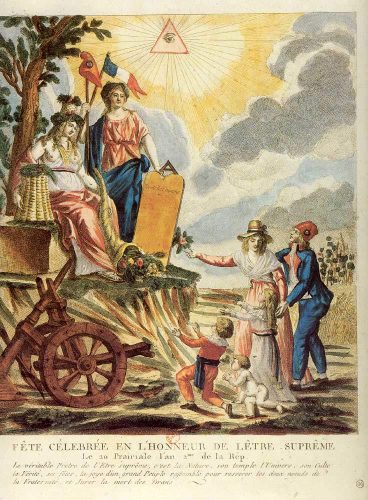

The National Convention’s May decree specified 20 Prairial, Year II (June 8th 1794) as the first Festival of the Supreme Being. It ordered the artist Jacques-Louis David to oversee the organisation of this festival.

The result was a tightly coordinated and choreographed series of marches and ceremonies. According to contemporary reports, the Festival of the Supreme Being in Paris had all the micromanagement, discipline and emotional fanfare of a Nazi rally. It began with speeches and a symbolic ceremony in the Tuileries garden, where a statue representing atheism was set alight.

The participants and crowd then proceeded to the Champ de Mars. There they found an enormous mountain, skilfully constructed by David out of timber and plaster, bedecked with rocks, shrubs and flowers, and illuminated with lights and mirrors. The mountain itself was a symbol of collective strength, of natural power, of mankind’s ascendancy and elevation toward heaven – and, of course, the Montagnard faction of the Convention.

Robespierre, dressed in a grand blue coat and gold trousers, led the deputies of the Convention to the top of the artificial mountain while the crowd looked on from below. Overlooked by a statue of Hercules atop a Doric column, the deputies recited oaths and sang verses of Le Marseillaise and other revolutionary anthems.

Public responses

Robespierre’s critics watched the Festival scornfully, noting how the ‘Incorruptible’ had placed himself in positions of great prominence. Jacques-Alexis Thuriot, an ageing politician once allied with Georges Danton, was not impressed by Robespierre’s speeches and histrionics. “Look at the bugger,” said Thuriot. “It’s not enough for him to be in charge, he has to be God”.

Most ordinary Parisians, however, responded well to the Festival. By 1794 they had grown accustomed to revolutionary festivals. They enjoyed the pomp and pageantry of these events, the respite from daily work and political conflict, the opportunity to remember what had been gained rather than arguing over what had not been achieved.

Some observers believed the Festival of the Supreme Being was a grander, more significant celebration than its predecessors. Jacobin newspapers, like the Journal de la Montagne, gushed about it, saying “this day consecrated to the Supreme Being will be the finest day in the life of the virtuous man… a simple ceremony, majestic and truly worthy of the eternal author of Nature”. Some who attended the Festival believed it marked an end to the Reign of Terror and revolutionary violence – a flawed hope, as Huet explains:

“One observer reported: “After the ceremony [the people] went to their homes with the tranquility and the propriety of a nation truly free. Today they have rejoiced at the change of place of the guillotine. I have heard a great number of citizens say: ‘With this change, the sword of the law will lose none of its effect, and we can enjoy a promenade which will become the finest in Europe’. According to Michelet, other people believed that the new cult also signaled an end to the executions. But far from signifying [this] it preceded, by just a few hours, the onset of what has been called the Great Terror. Indeed, two days after the Festival of the Supreme Being, the Convention voted the Law of 22 Prairial, submitted by Couthon (and generally thought to have been inspired by Robespierre).”

Failure and demise

For all its hope and grandeur, the Cult of the Supreme Being lasted only as long as Robespierre – which, as it turned out, was just another six weeks.

The contrived religious movement failed to capture the public imagination or win any natural support. Its ideas about creation, worship, personal conduct and destiny were vague and poorly explained. The new religion needed a charismatic and convincing leader to attract supporters and articulate a vision, qualities that Robespierre did not possess.

More significantly, Robespierre’s decision to position himself at the head of the Supreme Being cult only hardened his opposition. Several deputies who attended the Festival believed Robespierre showed signs of delusions and megalomania. These concerns contributed to the push to dispose of Robespierre in late July. After his execution, the Thermidorian Convention distanced itself from the Supreme Being movement, which without its creator and sponsor soon died a natural death.

1. The Cult of the Supreme Being was an artificial religion, developed by Robespierre and given formal status by the National Convention in May 1794.

2. In Robespierre’s mind, the Supreme Being was a deist god who created the world according to natural laws. The purpose of the cult was to educate the people and teach them morality and virtue.

3. The high point of the Supreme Being movement was a Festival, held in Paris and other locations in early June. It was marked by symbolism, pageantry and speeches celebrating the Enlightenment and regeneration.

4. The Paris Festival featured a gigantic artificial mountain on the Champ de Mars and featured speeches and gestures from Robespierre, who at his insistence played a leading role.

5. The Festival itself was popular with the people, however, the Cult of the Supreme Being failed to take hold, and Robespierre’s central role only increased his unpopularity among other deputies of the Convention.

Decree establishing the Cult of the Supreme Being (1794)

Witnesses to the Festival of the Supreme Being (1794)

Robespierre pays homage to the Supreme Being (1794)

Citation information

Title: ‘The Cult of the Supreme Being’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/cult-of-the-supreme-being/

Date published: September 15, 2019

Date updated: November 11, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.