The ideas and values of the revolution were expressed in many ways: through the visual arts, literature, music and popular culture, and in the ways people lived, dressed and communicated. French revolutionary culture was dominated by ideas of nationalism, progress, social unity and egalitarianism. The culture, style and symbols of the French Revolution were also used to demonstrate loyalty and commitment to creating a better nation. As the revolution radicalised, public shows of loyalty became particularly important, even potentially life-saving.

The tricolour cockade

One of the most famous symbols of the French Revolution was the cockade (French, cocarde), a tight knot of coloured ribbons pinned to one’s hat, tunic, lapel or sleeve. Cockades were a common device worn in the 18th century. Their colours were usually chosen to display one’s loyalty to a particular ruler, military leader or political group.

When Louis XVI returned to Paris on July 17th 1789, three days after the fall of the Bastille, he volunteered to wear a cockade of red and blue (the colours of Paris) to show his loyalty to the city. The traditional white of the Bourbon monarchy was added shortly after, reportedly by the Marquis de Lafayette, forming the famous tricolore (‘three colour’) cockade.

The tricolore became a prevalent and powerful symbol of the revolution, an emblem of national and class unity. In early October 1789 rumours reached Paris that the king’s soldiers had stomped tricolore cockades underfoot during a drunken party. The resulting outrage led to the march on Versailles, one of the most significant journées of the French Revolution.

Symbols of liberty

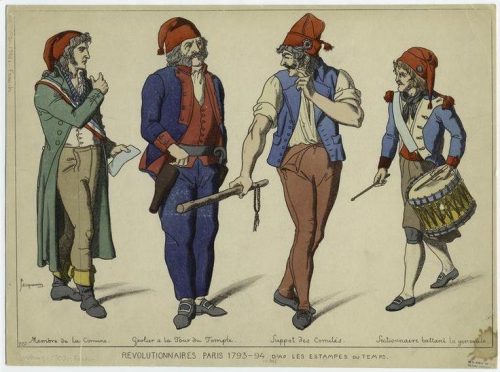

The French Revolution also borrowed symbols from classical mythology, the Enlightenment and the American Revolution. One of the most famous was the bonnet rouge or ‘liberty cap’.

This symbol, derived from the ancient Phrygian cap given to liberated slaves, had been used extensively during the American Revolution. A brimless bonnet of red wool or felt, the liberty cap symbolised freedom given to oppressed people. It was mainly worn by the urban working classes, particularly during the radical phase of the revolution.

Another American revolutionary symbol embraced by the French was the liberty tree, a symbol of fertility, growth and nature. Some art and visual propaganda featured Enlightenment symbols, like the Sun and the Eternal Flame (light), the fasces (strength through unity), the All-Seeing Eye (divinity), and pyramids and mountains (progress and elevation).

The symbology of the French Revolution also used human figures. The best known was Marianne, a female personification of the French nation not dissimilar to Britannia (Britain) or Lady Liberty (United States). Marianne was a young woman who depicted the new republic, a symbol of youth, regeneration and virtue.

The revolution’s artist

One man dominated the artistic culture of the French Revolution. Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) was a brilliant Paris-born artist, renowned for using classical stories and imagery as a vehicle for Enlightenment political values.

David supported the revolution from the outset, remaining in France while many of his fellow artists sought patronage abroad. Despite being a poor public speaker, he also became embroiled in politics, serving as a member of the National Convention, the Committee of General Security and the Committee of Public Education.

David is best remembered as the French Revolution’s painter-propagandist, the Jacobin artist whose works espoused radical revolutionary principles. Many of his paintings embodied the virtues and values of the new republic, including patriotism, egalitarianism, public service and self-sacrifice. David was not above distorting reality for political ends either, as reflected in his painting of the dead Marat (see below) or his oversight of the Festival of the Supreme Being in June 1794.

David’s famous works

David was a prolific artist but two of his works are remembered above all others. The first is David’s visual account of the Tennis Court Oath, a mural sponsored by the Jacobin club and the National Assembly but never finished to David’s satisfaction.

David’s drawing shows the significance and human drama of the event. Jean-Sylvain Bailly stands at the centre and administers the oath, while the other National Assembly deputies respond in a variety of ways, from pensive (Sieyès) to optimistic (Dom Gerle and the other clergymen) to exuberant (Robespierre). Above them, the curtains wave wildly, as if blown by the winds of political change.

Even better known is David’s dark but moving image of the vitriolic journalist Jean-Paul Marat. Using classical styling, David shows Marat in death as calmer, softer and more serene than he had been in life. His painting contains overtones of martyrdom and divinity, reminiscent of crucifixion scenes or Michelangelo’s Pieta.

To reinforce Marat’s alleged good character, David places a banknote and a letter in this hands, the letter reading “Give this banknote to the mother of five whose husband died defending the fatherland”.

“It was David’s task to portray this human wreck in a manner that aroused admiration. He removed all sign of skin disease and placed Marat’s body in an imaginary space. [It is] in a pose whose effect is particularly resonant: his limp arm hanging down, head lolling to one side and body half-leaning to face the spectator… This pose has been used for centuries to portray Christ’s descent from the Cross.”

Rose-Marie Hagen, art historian

Street fashion

The culture of the French Revolution was not confined to high art. The events of 1789-93 also changed how people lived, dressed and spoke.

Shifts in fashion were a noticeable outcome of the revolution. The ornate costumes of the aristocracy and haute bourgeouisie – a trapping of wealth and extravagance – had largely disappeared by 1791. Women stopped wearing hooped skirts and large headdresses, while men abandoned the use of powdered wigs (Maximilien Robespierre being one notable exception).

Simple and restrained dress – muslin frocks or dresses, neatly cut suits and tunics, modest wigs and hairstyles – became the order of the day. The red, white and blue tricolour remained popular as an expression of loyalty to the revolution; these colours were worn as cockades, ribbons or trimmings on a coat or tunic.

During the revolution’s most radical phase (1793-94) some Parisians replicated the trousers, tunics and simple headgear of the sans-culottes. Many of the sans-culottes dressed to mock and satirise victims of the Terror, shaving their heads or wearing a red ribbon around their throats.

Modes of address

The revolution also changed the way that individuals addressed and communicated with each other. In Paris and other cities and towns, traditional forms of address such as “Sire“, “Monsieur” and “Madame” were largely abandoned. The more egalitarian “Citoyen” and “Citoyenne” were used in their place.

Citizens also abandoned many of the formalities of pre-revolutionary society, including bows, curtseys and genuflection and the doffing of hats. The Scottish physician John Moore, who visited Paris during the revolution, wrote with some disapproval about this new way of doing things:

“There is in Paris at present a great affectation of that plainness in dress and simplicity of expression which is supposed to belong to republicans… People are saying ‘Tu’ or ‘Thou’ to each other. They have substituted the name ‘Citizen’ for ‘Monsieur’ when talking to or of any person, but more frequently, particularly in the National Assembly, they simply the use the surname… It has even been proposed in some of the newspapers that the custom of taking off the hat and bowing the head should be abolished, as [it is a remnant] of the ancient slavery and unbecoming the independent spirit of free men.”

Revolutionary music

The French Revolution also had its own soundtrack. The ideas of the Enlightenment and the revolutionary struggle were incorporated into poetry and song.

One of the first revolutionary songs was Ça Ira! (French for ‘it will be fine’), which appeared in the spring of 1790. The lyrics of Ça Ira! were optimistic and initially moderate, praising the National Assembly and the Marquis de Lafayette – but like the revolution itself, they changed over time, becoming more radical and violent. Another lively song that appeared in mid-1792 was La Carmagnole, which took aim at Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and the Swiss Guards.

The most famous of all revolutionary songs, however, was La Marseillaise, written by army engineer Rouget de Lisle after the outbreak of war with Austria in 1792. Written as a war song, La Marseillaise gained public popularity because of its broad sounds, its anthemic strains and the vigorous call to arms in its lyrics.

La Marseillaise was reportedly sung by some of the fédérés who stormed the Tuileries Palace in August 1792. It became a popular military song and was played wherever troops were being massed, mobilised or marched out. According to Lazare Carnot, a member of the Convention, La Marseillaise was so inspirational that it added 100,000 new recruits to the revolutionary army.

In July 1795, La Marseillaise was adopted as the national anthem of the French Republic, a title it still holds today.

1. The French Revolution was not only a political and ideological movement. Its ideas and values were also expressed in a variety of ways, including through symbolism, art, fashion and music.

2. The revolution was heavy with symbolism. Many, like the tricolore cockades and flags, were unique to France. Others were borrowed from ancient and classical symbolism and the American Revolution.

3. The revolution’s most famous artist was Jacques-Louis David, who sat in the National Convention, coordinated Jacobin festivals and painted works like the Tennis Court Oath and the evocative but propagandistic Death of Marat.

4. The revolution had an impact on the way that people dressed. The ornate costumes and hairstyles of the aristocracy were abandoned in favour of simpler forms of dress, and it became fashionable to mimic the dress of the sans-culottes.

5. Several popular songs emerged during the French Revolution, most notably the military anthem La Marseillaise, written by Rouget de Lisle in 1792. Ça Ira!, La Carmagnole and others were also widely sung.

Citation information

Title: ‘French revolutionary culture’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/revolutionary-culture/

Date published: September 30, 2019

Date updated: November 9, 2023

Date accessed: April 24, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.