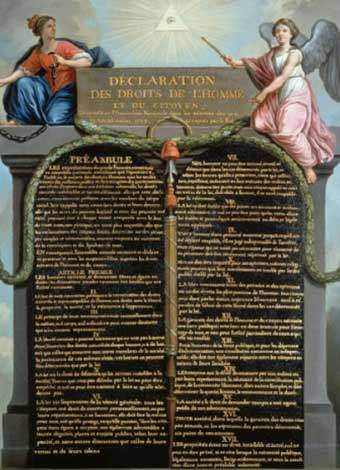

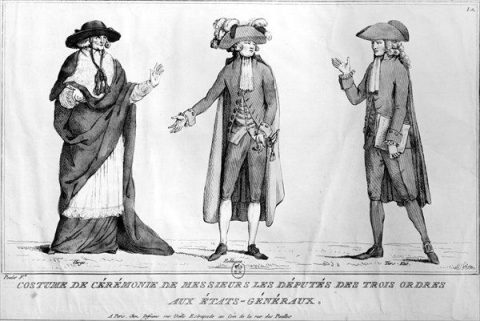

The revolutionaries of 1789 wanted a constitutional monarchy that was organised on sound democratic principles and accountable to the people. They also wanted to reform and simplify the way France was governed and administered. Under the Ancien Regime, France had grown into a cluttered and chaotic jumble of regions and jurisdictions, while its localised and haphazard systems of weights and measures made trade difficult. The new regime set out to rectify these problems – and went even further, even changing the nature of times and dates.

Administrative confusion

Under the Ancien Régime, France had become a confused array of administrative divisions and jurisdictions.

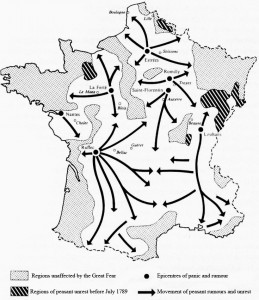

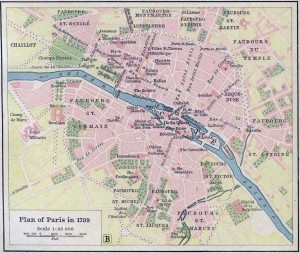

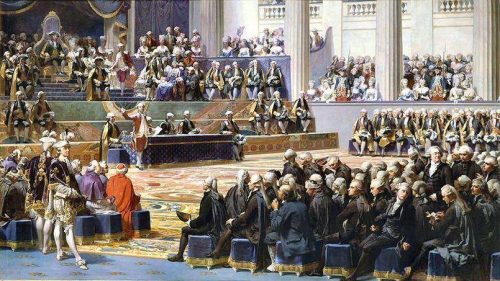

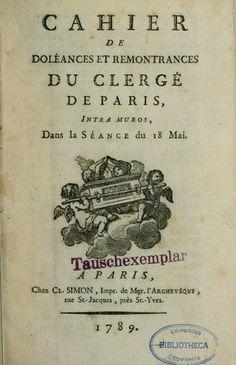

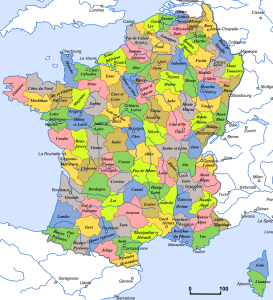

Maps of late 18th century France reveal just how complicated the nation had become, with its myriad of provinces, généralités, pays d’état, bailliages, parlements, dioceses and parishes. These divisions often had overlapping or conflicting borders, employed different tariffs and duties, had different customs regulations and used different systems of weights and measures. To further complicate government, the expansion of the national bureaucracy under Louis XIV had created new offices and positions without abolishing ancient ones.

Because of this unregulated and inefficient growth, France’s government and bureaucracy became top heavy, cumbersome and difficult to reform. As historian Sylvia Neely puts it, the Ancien Régime was like “a large palace to which rooms and wings were added over the years, without any overall plan”.

Remaking the map

The new regime wanted to address these issues by remaking France from scratch. Maps of the Ancien Régime would be wiped clean and redrawn with a steady hand. Old provinces would be scrapped and replaced with new administrative divisions, their borders and powers decided rationally.

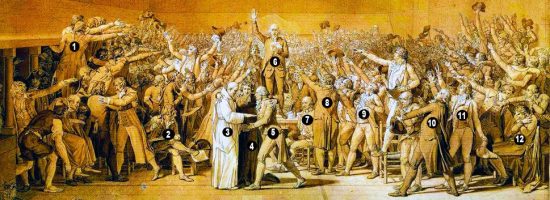

The task of administrative reform was begun by a committee of the National Constituent Assembly. Most of the committee’s recommendations were passed on March 4th 1790. These reforms abolished the provinces (généralités and pays d’états) and replaced them with 83 départements.

These new départements were much smaller than the previous provincial divisions – an intentional decision, made to limit the power of the départements and ensure that département officials could respond quickly to unrest or problems (the departmental capital, or chef-lieu, was never more than one day’s travel away from the rest of the département).

The départements were given responsibility for gathering taxes, overseeing public works, providing education and dispensing charity. In addition to their secular duties, each département also constituted a new religious diocese. This greatly reduced the number of dioceses (down from 130 in 1789) and therefore the number of bishops and archbishops.

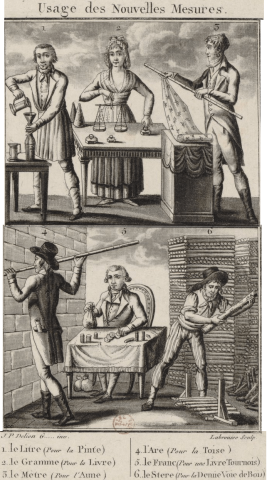

Weights and measures

Once it had streamlined France’s administrative divisions, the National Constituent Assembly turned its attention to simplifying and standardising weights and measures.

The systems for weighing and measuring items in the Ancien Régime were notoriously confusing. Before the revolution, France used more than 100 different ways of dividing and measuring land. Units of weight and measurement were usually determined by local custom, city officials or feudal seigneurs.

This meant that standards were often fixed locally – for example, units of length for rope, cloth or building supplies might be measured against a beam at the town market or markings on a cathedral wall. Weights were often determined by containers – baskets, barrels, carts and so forth – but the size of these could vary considerably from one place to the next.

The lack of national standards and consistency was particularly frustrating for merchants, importers and wholesalers who traded in different regions. In March 1790, the National Constituent Assembly resolved to adopt a uniform system of weights and measures – however there were several ideas about how to proceed and contention about what system to adopt.

The metric system

Being a technical matter, the Assembly left the issue of weights and measures with the Académie Française, the nation’s elite scientific academy. Among the contributors to the debate were Charles de Talleyrand, the noted chemist Antoine Lavoisier, Italian mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange, the ‘French Newton’ Pierre-Simon Laplace and the Marquis de Condorcet.

Of these luminaries, Lagrange, Laplace and Condorcet sat on the Académie’s committee. On October 27th, they recommended the adoption of a decimal system – that is, a system where units of weight and measurement were based on divisions or multiplications of 10. On March 19th 1791, the Académie presented a further series of recommendations, one being the use of the metre (French for ‘measure’) as a base unit of distance.

The National Constituent Assembly gave approval for the Académie to continue developing what is now known as the metric system. The system they eventually presented to the National Convention in 1793 created new units of measurement called metres, grams and litres. Prefixes derived from Greek – deci, centi, milli, deca, hecto, kilo – were used to indicate divisions or multiples of these units.

Adaptation and spread

The men of the Académie were pleased with their creation. The metric system was based on mathematics, geometry, physics and longitude, yet its decimal base meant that it was practical, functional and easy to calculate. “Nothing so great and so simple”, said Antoine de Lavoisier, “has ever come from the hand of man”.

The Académie’s scientists believed the new system would become popular in France, then spread around the world. Revolutionary politicians also supported the proposed new system. The Assembly’s 1791 decree had as one of its aims “extending this uniformity to foreign countries… committing them to a new measuring system [based on] nothing arbitrary or peculiar to the situation of one people of the world”.

Their predictions were largely justified but it would take years before the new system was embraced in France, let alone worldwide. The National Convention fixed July 1st 1794 as the date when the metric system would become compulsory. But by the time this date arrived, almost all French citizens – including most government departments – were still using old systems of weights and measures. The national government’s failure to supply ‘metre sticks’, standardised weights and educational material about the new system was partly to blame.

Changing time

As the Académie was devising its metric system, a like-minded group began lobbying for changes to the measurement of time. Unlike the reforms to weights and measures, there was no pressing need to change the clock or the calendar. This was a movement driven more by ideology and utopian dreams than practical need.

The Gregorian calendar was a creation of the Catholic church, for example, and thus seen as an artefact of the old order. Some in the government and the Académie saw intervals of time as simply another measurement, to be decimalised along with weights, lengths and volumes. Others had grander visions about reforming society on rational principles or restarting the calendar from scratch.

Whatever the motives, the National Convention gave its support to decimalised time in September 1792. It handed the matter to one of its sub-committees, the Committee of Public Education (French, Comité de l’instruction Publique) and the mathematician Gilbert Romme, the committee’s de facto leader. Romme finalised his recommendations while held hostage in Caen during the federalist revolt there. They were officially adopted by the Convention on October 5th 1793.

A 10-hour day, a 10-day week

The premise of Romme’s changes was relatively simple. The measurement of time should also be decimalised: radically reorganised so that it was based on units of 10. There would be 100 minutes in an hour, 10 hours in a day and 10 days in a week. A new decimal minute would be the equivalent of 86 ‘old’ seconds; the decimal hour would span 144 ‘old’ minutes.

The number of months in a year remained at 12, however, each month would contain three 10-day weeks. Months were named after aspects of nature or climate relevant to that time of year, for example Brumaire (‘fog’), Frimaire (‘frost’), Germinal (‘germination’), Floréal (‘flowering’), Prairial (‘pasture’) and Thermidor (‘heat’).

The days of the week were numbered rather than named, while the 10-day weeks were known as décades. This decimalisation still left five or six days left over at the end of each calendar year. These surplus days were called jours complémentaires (‘complementary days’) or sanculottides, because they were designated holidays for the working classes.

Gregorian years were replaced by numbered years, beginning with Year I, the first year of the French Republic (September 22nd 1792 to September 21st 1793).

Initial optimism

These reforms were supported with printings of the new calendar, government publications and the design and production of new timepieces. Clockmakers produced clocks and watches that showed decimal time or, more commonly, a combination of decimal and 24-hour time. The government, its departments and agencies all used revolutionary dates and times in their reports and correspondence.

The men who devised the revolutionary calendar and decimal time gushed about the progressive social change they had fathered. Fabre d’Eglantine described it as a victory for Enlightenment principles:

“The regeneration of the French people and the establishment of the Republic have brought with them the reform of the common calendar. We could no longer count the years during which kings oppressed us… the prejudices of the throne and the church, and the lies of each, sullied each page of the calendar we were using. You have reformed this calendar and substituted another, in which time is measured by more exact, symmetrical figures… it is necessary to replace visions of ignorance with the realities of reason, sacerdotal prestige with the truth of nature.”

Adaptation and reception

Among the general population, these reforms were not warmly received. It is difficult to accurately gauge public opinion, not least because the first year of the revolutionary calendar coincided with the Reign of Terror. To criticise the Convention’s reformist policies on time was to risk condemnation as a counter-revolutionary.

This was particularly true in Paris, the epicentre of the Terror, where the revolutionary calendar was more widely used. The working classes expressed some bitterness that the new calendar reduced their four Sundays or rest days each month down to three.

Outside the cities and larger towns, however, life went on as before. Peasants and workers continued to follow the Gregorian calendar and the seven day week; they continued to observe Sundays as a day of rest and worship. Government officials tried to fine those who breached the designated rest days or continued to observe Sundays and Christian feast days – but it had little effect.

By the end of the 18th century, the revolutionary calendar had fallen into widespread disuse. It was formally abolished by Napoleon Bonaparte in January 1806.

“We cannot escape the fact that the calendar was a failure. For most of the years of its existence, we can detect an awkwardness, even an embarrassment about the artificiality of the new system, its continued coexistence with the old, forbidden calendar, and its contrast with the calendar used by the majority of other nations. Its existence and widespread disuse was a constant reminder that the aims of the Revolution had not been achieved, and an admission that the republic was, at best, a work in progress.”

Matthew Shaw, historian

1. The revolutionary government in France attempted to reform the nation by changing its administrative divisions and creating a standardised system of weights and measures.

2. In 1790 the National Constituent Assembly abolished the old provincial divisions, replacing them with 83 départements of limited power and roughly equal size. The départements also served as ecclesiastical dioceses.

3. In consultation with scientists in the Académie, the government also sought to develop a system of weights and measures, to replace the myriad of systems in use in pre-revolutionary France.

4. After adopting the metric system, the National Convention also advocated a revolutionary calendar and decimalised time, based on units of 10. This came into effect in 1793.

5. The adoption of the metric system was slow and not complete by the mid-1790s, while the revolutionary calendar and decimal time were widely ignored by the French people and eventually abolished in 1806.

Citation information

Title: ‘Remaking France’‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/remaking-france/

Date published: October 23, 2019

Date updated: November 9, 2023

Date accessed: May 2, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.