The cahiers de doléance (French for ‘ledger of complaints’) were books or ledgers containing public grievances and suggestions. They were requested by the king in January 1789 and drafted and compiled in the months that followed, before being submitted to the Estates General. Though somewhat tempered and not representative of all views, the cahiers are a valuable source for understanding the mood of the people on the eve of revolution.

The king calls for opinions

Louis XVI announced the convocation of the Estates General in an August 1788 edict. In January 1789, a further royal edict ordered the electors in each district to compile a cahier de doléance.

According to the January edict, the content of these cahiers would be considered when addressing “the needs of the state, the reform of abuses, the establishment of a permanent and lasting order [for] the general prosperity of the kingdom”.

The opportunity to submit complaints and feedback to the royal government was rare, so thousands of French citizens threw themselves into the task with relish. Some historians have suggested the political mobilisation and public debate that compiled the cahiers had a greater impact than the cahiers themselves. Around 40,000 cahiers de doléance were produced, many of which survive today.

Compilation

Each of the Three Estates submitted their own cahiers. The cahiers of the First Estate and Second Estate were drawn up at specially convened assemblies.

Third Estate cahiers were compilations rather than original documents. They began as lists drafted by registered voters, aged 25 and above, in every town, parish, village or guild. These lists were then sent to electoral assemblies, most of which were dominated by bourgeois lawyers and officials. These assemblies reviewed and consolidated the lists into a formal cahier.

Because of this process, the final Third Estate cahiers tended to be filtered summaries rather than raw expressions of the grievances of workers and peasants. According to Merrick Whitcomb, “this method of assembling the local cahiers of the Third Estate resulted in a loss of vigour and personality”. Other historians agree that the final cahiers submitted by the Third Estate were more subdued than the original lists of grievances.

“Members of some 40,000 bodies… assembled, deliberated and sent statements either to intermediate assemblies or directly to the Estates-General. In most cases, local people neither emitted empty rhetoric nor adopted formulas given them by external authorities. They took the opportunity seriously, wrangling or agonising item by item over the contents of collective demands. They produced a set of documents resembling the ballots of a national election in some regards, a national poll in other regards…”

Charles Tilly, historian

Restrained complaint

The vast majority of cahiers did not propose or demand radical political change. Most cahiers were framed politely and deferentially, expressing their loyalty, devotion and supplication to Louis XVI. They thanked the king for the opportunity to have their say and expressed trust that he could reform and improve the nation.

The Third Estate of Carcassonne, for example, promised their “beloved monarch, one so worthy of our affection” the “unmistakable proof of its love and respect, of its gratitude and fidelity”. The commoners of Dourdan humbly thanked the king for being permitted to bring “grievances, complaints and remonstrances to the foot of the throne”.

If there was any revolutionary sentiment in the cahiers then it was buried beneath this royalist sycophancy and grovelling. But while the cahiers were not revolutionary in their tone, within their specific grievances were contained the ingredients for a revolution.

Political grievances

There was a surprising level of agreement across the cahiers of all three estates, particularly about social and political issues. The three estates accepted the principle of constitutional reform and welcomed a move towards representative government in the guise of the Estates General.

The more radical cahiers insisted that the Estates General meet regularly. The Third Estate of Paris, for example, wanted it to meet “at three-yearly intervals”. The cahiers were more divided about the composition of the Estates General and voting procedures. The clergy and nobility wanted ‘voting by order’ at the Estates General, while the Third Estate, echoing the demands of Emmanuel Sieyès and other pamphleteers, sought ‘voting by head’.

The question of tax reform was just as divisive. The peasantry and urban workers were most concerned about disproportionate and rising levels of taxation, particularly the tax on salt (gabelle).

Third Estate cahiers

Third Estate cahiers are of significant value for those seeking causes of the French Revolution. Peasant cahiers are the most radical and the most illuminating.

Various studies of peasant grievances have identified three consistent themes: the lack of equity and fairness in taxation, the need to abolish or reform the seigneurial system, and the burden of payments to the church. Historians Gilbert Shapiro and John Markoff, who have completed a large survey of parish cahiers, found that 42 percent wanted taxation reform and a further 24 percent demanded the abolition of specific taxes. More than 75 percent wanted changes to seigneurialism, with almost half this number calling for the abolition of all feudal dues, without compensation to seigneurs.

Aside from Paris, which was more radical, urban cahiers tended to reflect bourgeois concerns and interests. One such cahier, submitted in March 1789 by the Third Estate in Saint-Vaast, listed four main concerns, three of which were political or legal:

- The abolition of lettres de cachet. The cahier called for an end to arbitrary detention and punishments, to be replaced by due process in arrests, trials and imprisonment.

- The nation should be consulted and give its agreement about any new taxes the king planned to levy on the people. Taxation should fall equally on all classes, including the nobles and the clergy.

- The Estates General should be convened every four years.

- Members of the Third Estate should have access to justices in the parlements.

Many of these Third Estate cahiers engaged in what Ian McNeely calls “political ventriloquism”: the act of bourgeois lawyers speaking on behalf of a large and diverse Third Estate.

Historical significance

As political and legal documents, the cahiers are certainly framed in a civil and restrained way that dulls raw opinion and ignores or dilutes particular grievances. For all their limitations, the cahiers remain our best source for understanding the mood of the French people on the eve of revolution.

David Andress considers the cahiers “the expression of France from below… in purely social terms but also in terms of geographically anchored expectations, concerns and aspirations”. The 19th-century historian Alexis de Tocqueville called them “the swan song of the old regime, the ultimate expression of its ambitions, its last will and testament”.

1. The cahiers de doléance were books or ledgers of grievances, drafted and collected from each Estate in each district in early 1789, then forwarded to the Estates General.

2. The compilation of the cahiers was ordered by Louis XVI as a preparatory measure for the Estates General, ostensibly to help the assembly understand problems and formulate policies.

3. The cahiers reveal common trends and grievances across all three Estates, particularly on social and political matters – but there was division on how to address taxation and voting at the Estates General.

4. Studies of the Third Estate cahiers suggest a large majority of French commoners wanted to abolish seigneurialism, in whole or in part, and to address inequality in taxation.

5. The cahiers remain our best sources for understanding the mood of the French people on the eve of the revolution, though Third Estate cahiers tend to reflect the language and interests of the bourgeoisie.

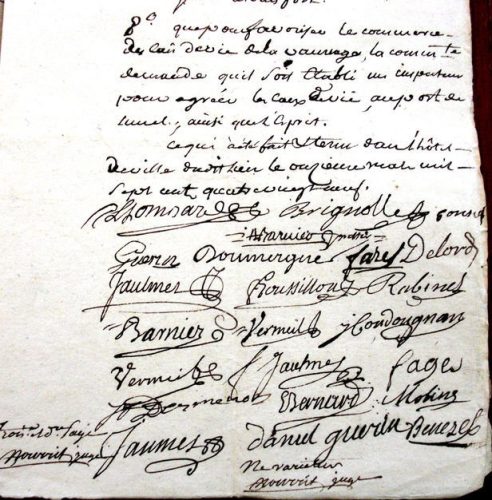

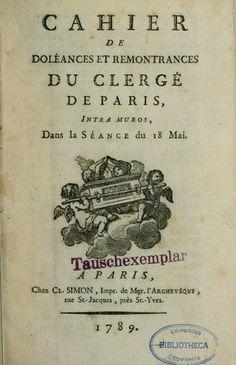

Louis XVI orders the compilation of cahiers de doléance (1789)

The cahier of the First Estate in Saint-Malo (1789)

The cahier of the Second Estate in Roussillon (1789)

The cahier of the Second Estate in Berry (1789)

The cahier of the Third Estate in Carcassone (1789)

The cahier of the Third Estate in Gisors (1789)

The cahier of the Third Estate in Levet (1789)

The cahier of the Third Estate of Paris (1789)

The cahier of the Third Estate in Versailles (1789)

The cahier of peasants in Menouville (1789)

The cahier of the shoemakers of Pontoise (1789)

Citation information

Title: ‘The cahiers de doléance‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/cahiers-de-doleance/

Date published: October 22, 2019

Date updated: November 9, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.