On August 10th 1792, the people of Paris laid siege to another royalist stronghold. This time, their target was the Tuileries Palace, the official residence of Louis XVI in the capital and the location of the Legislative Assembly. Marked by scenes of slaughter and debauched violence, the attack on the Tuileries produced rapid and radical political change, bringing to an end the constitutional monarchy formed in 1791.

A dilapidated castle

The king and his family had been resident at the Tuileries since the people of Paris marched on Versailles in October 1789 and forced their return to the capital. The Abbé Pous, a witness to these events, wrote “from now on our monarchs will live at the Tuileries; this revolution took less than 24 hours”.

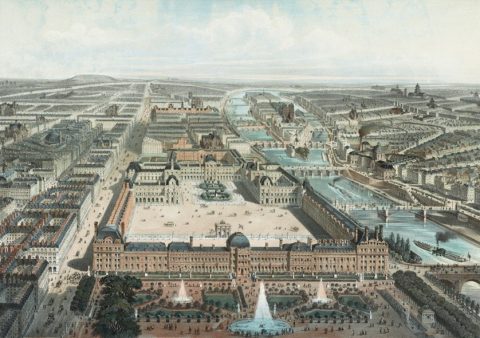

The Tuileries was a dilapidated royal castle on the right bank of the Seine, constructed in the mid-1500s and not used as a regular royal residence since the days of Louis XIV.

For the royal family, life in the Tuileries was a considerable step down from the grandeur of Versailles. There was no hunting, no carriage rides in the grounds, no Petit Trianon or Hameau de la Reine. Parisian newspapers cheekily reported that the king’s only hobby at the Tuileries was walking around the castle until “healthy perspiration required him to stop”.

The royal court

After the journee of October 1789, the royal court continued to operate at the Tuileries, as it had at Versailles. The king was still attended by nobles and foreign dignitaries, and his court maintained many of its rituals and at least some of its grandeur. There was no serious opposition to this in the National Constituent Assembly. The deputies thought it necessary to maintain a grand royal court to impress foreign visitors and uphold national prestige.

Nevertheless, the Assembly spent weeks discussing cuts to royal spending. In consultation with the king, the Assembly voted to cut spending on the royal household to 25 million livres, a reduction of around 15-20 million livres from the old civil list. The king retained ownership of several larger palaces and land holdings, most notably Versailles, Saint-Cloud and Fontainebleau, while others were sold to alleviate the national debt.

These cuts satisfied most, though they did not go far enough for the radical political clubs and sans-culottes of Paris.

Incidents at the Tuileries

According to Lafayette, a regular visitor to the palace, the only sign the king was not free was the fact he no longer went hunting. The royal family’s surroundings were comfortable and extravagant. They were attended by dozens of servants and the king was courted by foreigners and nobles.

For all this, however, Louis was a captive. His presence in the capital was a focal point for Parisian mobs. Occasionally, their exuberance manifested as hostility and confrontation.

On February 28th 1791, a group of 400 noblemen, hearing rumours that an attack on the king’s life was imminent, took up arms and entered the Tuileries to protect him. A standoff between the noblemen and a growing crowd of sans-culottes developed and threatened to erupt into violence. The nobles were eventually disarmed by Lafayette and sent home at the king’s command. This journée became known as the ‘Day of Daggers’ or the ‘Poignard conspiracy’.

Several weeks later, in April, another working-class mob gathered at the gates of the Tuileries, blocking the royal family’s carriage and preventing their departure for a summer residence at Saint-Cloud. This confrontation confirmed the king’s status as a virtual prisoner in the Tuileries. It may have been the tipping point in his decision to flee Paris in June.

Rising anti-royalism

Events in the summer of 1791 further endangered the king. The flight to Varennes (June 1791) saw the royal family returned under guard to the Tuileries, where they now lived under more visible house arrest. Jacobin and Cordeliers petitions calling for a republic, and the Champ de Mars massacre that followed (July 1791), were evidence of the rising anti-royalism in Paris.

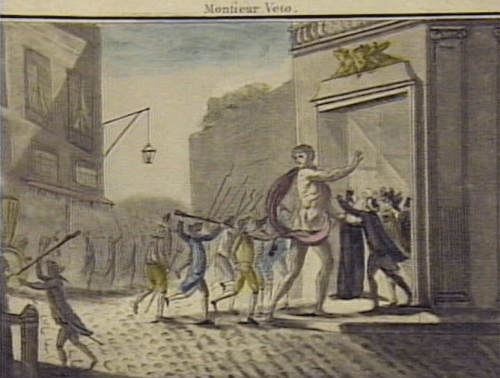

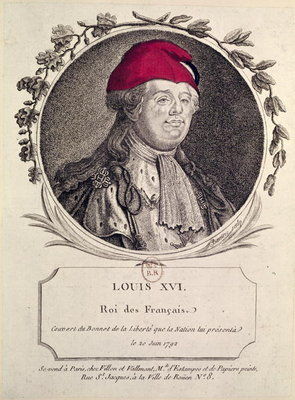

In the final two months of 1791, the king further riled the people by vetoing the Legislative Assembly’s decrees on émigrés and non-juring priests. In June 1792, an armed crowd stormed the Tuileries, condemning the king as “Monsieur Veto” and demanding he pass all decrees. A group carrying weapons and a small artillery piece gained access to the king’s quarters and one man bearing an axe approached the king.

Louis XVI managed to quell the invaders by listening to their demands and politely promising to consider them. He then donned a red liberty bonnet and toasted the health of the nation. In another room, the queen and her children were also surrounded by a hostile mob. Marie Antoinette‘s 14-year-old daughter later described the incident:

“We were obliged to stay there and listen to all the insults that these wretches said to us as they passed. A half-clothed woman dared to come to the table with a bonnet rouge in her hand and my mother was forced to let her place it on her son’s head. As for us, we were obliged to put cockades on our heads. It was, as I have said, about eight o’clock when this dreadful procession of rioters ceased to pass and we were able to rejoin my father and aunt.”

Suspicions grow

These outrages against Louis XVI and his family, along with the king’s polite and courageous response, won the royals a measure of sympathy and respect. This was not to last.

By late July 1792, the situation in Paris had deteriorated further. Economic conditions remained dire and were exacerbated by the threat of foreign invasion. On July 25th 1792, the Duke of Brunswick issued his notorious war manifesto, threatening to wreak vengeance on Paris if the king or his family came to any harm. On the streets of the capital, rabble-rousing journalists like Jean-Paul Marat and Camille Desmoulins whipped up anger towards the king, Lafayette, Jean-Sylvain Bailly, the Legislative Assembly and the still-moderate Paris Commune.

By the first days of August, Paris was filled with rumours about the fate of the king. Some believed the Austrians and Prussians were about to stage a daring raid to rescue Louis and his family from the Tuileries. Others believed the king was plotting another flight, this time to Rouen.

Radicals seize the Commune

Unlike the transgressions of June, the August insurrection had planners and leaders, most notably the Cordeliers orator Georges Danton and Jacobin powerbroker Maximilien Robespierre.

On August 9th delegates from the sections occupied the Hôtel de Ville and took control of the Paris Commune. It was reformed as an ‘Insurrectionary Commune’, the ranks of its council now dominated by sans-culottes instead of bourgeois lawyers. The following day a mob formed, peopled from the sections and backed by the political clubs and the new Commune. It was joined by several units of Fédérés (radical republican troops of the National Guard) from Brittany and Marseille.

Together, this coalition of soldiers and sans-culottes crossed the river and marched west to the Tuileries. The palace was protected by a garrison of loyalist National Guard, as well as hundreds of gendarmes and almost a thousand soldiers of the Swiss Guard (foreign mercenaries hired to provide the king’s bodyguard).

Tactically, the Tuileries should have been easy to defend. It had strong fortifications, it was protected on one side by the Seine and, unlike the Bastille, was heavily manned. But the gendarmes and National Guard in the Tuileries were unreliable. Anticipating a massacre, most fled during the night of August 9th.

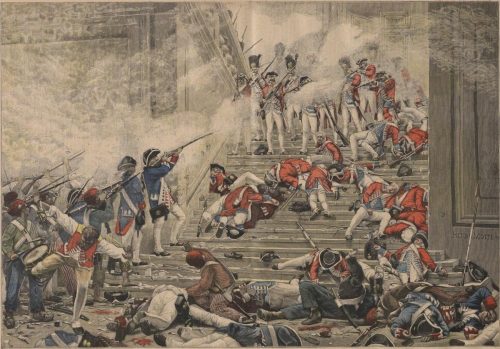

The palace attacked

By dawn on August 10th, a crowd of several thousand people was massing outside the Tuileries. Newcomers arrived so quickly from the sections that according to one news report, 25 people were killed in the crush. Most of the crowd were carrying some kind of weapon: guns, sabres, pikes, daggers, scythes, iron bars and pieces of wood.

After surveying the situation, the king concluded that it was impossible to defend the palace without risking the lives of his defenders and slaughtering thousands of Parisians. Leaving orders with the guard, Louis and his family walked across the Tuileries garden and took refuge in the Legislative Assembly building. Meanwhile, back inside the palace, rebellious soldiers and civilians breached the palace gates and poured into the Tuileries courtyard.

Exactly happened next is a matter of dispute. Whatever the cause, members of the mob and advancing fédérés engaged in a pitched battle with the Swiss Guard. The Swiss held them off until around midday when their ammunition ran out and they were overrun.

Massacre of the guard

“The massacre followed the sacrificial logic of the scapegoat: unable to vent their violence upon its intended object, the king, the revolutionaries chose victims who symbolised the sovereign power of the king and whose deaths could serve to unify the people… The destruction of the Swiss Guard allowed the revolutionaries to usurp and transform the royal notion of the body politic. This outcome is captured by reports the massacre of the Swiss was accompanied by cries of ‘Vive la nation!’, replacing ‘Vive le roi!’.

Jesse Goldhammer

What followed was a scene of tremendous butchery. More than two-thirds of the Swiss Guard were slaughtered, many of them hacked to death by axe-wielding sans-culottes. Heads were removed and displayed on pikes or kicked around for sport. Body parts were dismembered and waved around, then fed to dogs.

Hordes of women from the city’s underclass followed behind the advancing soldiers, stripping the corpses of Swiss Guardsmen of their uniforms and belongings, scything off genitals and stuffing them into their mouths of their former owners. Courtiers and palace staff were not spared either, several suffering a similar fate.

By the end of the day, some 650 Swiss Guards were dead while the remaining 250 were captured, beaten and thrown into the city’s prisons. Four weeks later, almost all of the guards who survived the carnage of August 10th were killed during the September Massacres.

The king accedes

Meanwhile, the king, his family and his inner circle sought refuge in the chamber of the Legislative Assembly. Under the leadership of the skilled orator Pierre Vergniaud, the Assembly agreed to provide the king with sanctuary. The promise was a hollow one since the Assembly building was largely unguarded.

By midday, the hall was surrounded by thousands of republican soldiers and armed Parisians. The Assembly’s deputies received an ultimatum, via members of the radical Commune, demanding the abolition of the monarchy and the voluntary dissolution of the Assembly itself. Their position effectively hopeless, the Assembly’s deputies quickly acceded to these demands.

On August 11th, the Legislative Assembly voted to suspend the king, replacing him with a five-man executive council. It also convened democratic elections for a new national convention, scheduled for the following month.

Sweeping political change

This 24-hour period produced more political change than any of the French Revolution’s other journées. In the space of hours, France was transformed from a constitutional monarchy to a republic. The deposed king and his family were removed to and imprisoned in the Temple, a former monastery in northern Paris.

The Legislative Assembly, under pressure from the Commune, voted itself into oblivion and prepared to hand power to a new national convention. The Constitution of 1791 was abandoned and its distinctions between active and passive citizens were discarded. Elections for a new national legislature would be based on universal suffrage. On August 25th, the Assembly also voted to abolish all feudal dues without compensation, unless the seigneur could produce a valid contract (which few of them could). This effectively ended seigneurialism in France.

In Paris itself, the moderate Paris Commune was overthrown and refilled with radicals from the sections. The revolutionary Commune, now under the control of Danton and other radicals, held sway in the capital, silencing Royalist and moderate publishers and arresting scores of nobles and non-juring priests.

The Marquis de Lafayette, outraged at the events of August 10th, tried to organise a counter-revolution to restore the monarchy. Unable to drum up enough support, and facing arrest himself, Lafayette fled France and the revolution and ended up a prisoner of the Austrians.

1. The August 10th 1792 attack on the Tuileries was an insurrectionary action by Republican soldiers and the people of Paris, who wanted to depose the king and abolish the monarchy.

2. This attack was fuelled by poor economic conditions, foreign aggression, fears of foreign invasion, the king’s use of the veto power and rumours of another royal attempt to flee Paris.

3. On August 9th radicals seized control of the Paris Commune, a move planned and carried out by the Paris sections and members of the radical political clubs.

4. The following day soldiers and civilians marched on the Tuileries, the royal residence in Paris. While the king fled and took refuge in the Legislative Assembly, the attackers invaded the Tuileries and slaughtered most of the soldiers there.

5. In the aftermath of this attack, the Legislative Assembly suspended the king, abolished the monarchy, cancelled unverified feudal dues, voted for its own dissolution and convened elections for a new national convention.

Citation information

Title: ‘The attack on the Tuileries’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/attack-on-the-tuileries/

Date published: September 19, 2019

Date updated: November 6, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.