Seigneurialism was a system of rural organisation and land tenure used in 18th-century France. The basis of the seigneurial system, which originated from medieval feudalism, was almost entirely economic – it required peasants who occupied land owned by a seigneur to provide him with feudal dues and unpaid labour. These obligations and the seigneurial system that underpinned them were significant sources of dissatisfaction and grievance in the late 18th century.

Feudal origins

French seigneurialism was a system partly derived from feudalism, the dominant political, social and economic system in Europe during the Middle Ages. Medieval feudalism was a hierarchical system that organised communities so they could feed, supply and defend themselves.

Though inherently unequal, feudalism bound different social classes together with a series of bonds or obligations. The lord allowed peasants or serfs to work his land. In return, the peasants handed over a proportion of their grain or produce to the lord. The lord also shared land with his knights, who helped the lord defend his realm. All classes contributed to the church with gifts and tithes, believing they would facilitate blessings from God.

These feudal relationships and commitments provided medieval Europeans with enough sustenance, stability and security to survive in small communities through sometimes dangerous periods.

Seigneurialism emerges

Medieval feudalism in its entirety died out in France before the 1500s. By the turn of the 1700s, France had a strengthening national government and a rapidly changing economy – yet remnants of feudalism lingered in many rural areas. This diluted form of feudalism, which historians now call seigneurialism, was chiefly economic and concerned only with ownership and tenure of the land.

That some ideas and practices of medieval feudalism continued to exist within a growing capitalist economy was an anachronism. Yet seigneurialism was defended by the French nobility and the church – even by wealthy members of the bourgeoisie, who hoped one day to be seigneurs themselves.

As historian Jack Censer put it, “French society was a kind of hybrid, neither entirely free of the feudal past nor entirely caught up in it”.

“In the 1780s a French lord could collect a variety of monetary and material payments from his peasants; could insist that nearby villages grind their grain in the feudal mill, bake their bread in the feudal oven, press their grapes in the feudal wine press; could set the date of the grape harvest; could have local cases tried in his own court; could claim particularly favored benches in church for his family and point to family tombs below the church floor; could take pleasures forbidden the peasants – hunting, raising rabbits or pigeons.”

John Markoff, historian

Seigneurialism in operation

Seigneurialism was framed as being mutually beneficial but the reality is that it was inherently one-sided, with many benefits for the lord and few, if any, for the peasant.

The seigneur doled out sections of his estate in small plots to individuals, families or small groups. Those who occupied and worked the seigneur’s land were subject to a range of feudal dues, including the champart (paid in grain or produce) and the cens (paid in cash).

Where the system was strongest, the landowner could hold a seigneurial court within his estate and pass legal judgement on peasants who lived there. There were over 70,000 of these courts in place, though they operated very infrequently, some not sitting for many years.

Seigneurs could also demand the much-loathed corvée, which required each male peasant to provide several days of unpaid labour on the seigneur’s own projects. This usually took the form of working their private land or repairing buildings, fences, bridges or roads.

The seigneur often owned the flour mill, the baker’s oven and the grape press – all critical infrastructure in a rural village – and required annual payments for their use (banalités). In some regions, the seigneur was the only party permitted to own male pigs or cattle, for which he charged a stud or breeding fee.

A coveted position

Most seigneurs were nobles, though this was not always the case. Many members of the clergy and upper bourgeoisie purchased seigneuries (feudal estates) in the 17th and early 18th centuries. The status and trappings of the seigneur – the collection of feudal dues, exclusive hunting rights, an individual pew in the local church and so on – were prestigious and highly sought after.

The seigneurial system came under attack throughout the 1700s. Many philosophes condemned the historical origins of seigneurial dues, most of which stemmed from medieval ideas of fiefdom and fealty but were without real legal basis.

They also criticised the seigneurial system for its inequality, noting that in some seigneuries, the peasants existed as virtual slaves. Several radical economists suggested that seigneurial economics held back agricultural production. A more open labour market, they argued, would benefit economic progress.

The administration and paperwork involved in maintaining the seigneurial system were also extensive and complex. Unlike the Middle Ages, 18th-century feudal dues were usually outlined in contracts and deeds associated with land tenure.

Contribution to revolution

To what extent was seigneurialism a critical grievance leading to the French Revolution? This question has long interested historians. It is difficult to answer generally because seigneurial dues took different forms from place to place and were levied more rigorously in some parts of France than others. Seigneurial dues were proportionately heavier in northern France, for example, than in the south, at least for the champart and cens.

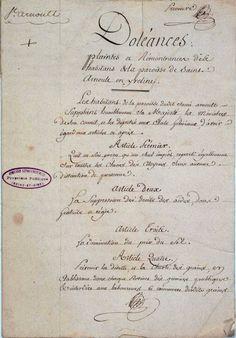

Regardless of this inconsistency, opposition to seigneurial dues was quite widespread across France. The best evidence for this can be found in the cahiers de doléance, the grievance books drawn up in early 1789 for submission to the Estates General.

Rigorous studies of cahiers drafted by the Third Estate show almost no support for retaining feudal rights as they stood. The majority of the cahiers (55 percent) suggested abolishing the champart and cens, albeit with some compensation to the seigneur. A smaller proportion (36 percent) suggested reforming or merging these payments. The cahiers were similarly opposed to the banalités, arguing that they be abolished with (43 percent) or without (40 percent) compensation to the seigneur.

1. Seigneurialism was a system of land tenure used in some rural areas of 18th century France. It was derived from and contained aspects of medieval feudalism.

2. Unlike medieval feudalism, which connected social classes and provided stability and security in a small community, 18th-century seigneurialism took the form of a land contract between the seigneur (lord or landowner) and the peasant farmer.

3. In seigneurial holdings, peasants were required to make annual payments to the seigneur, either in cash (cens) or with produce (champart). The seigneur also charged taxes for using infrastructure like the flour mill, wine press and baker’s oven (banalités).

4. The seigneur could also demand a period of unpaid labour from his tenants, called the corvée. Many peasants were also subject to seigneurial courts, which were overseen by the seigneur.

5. The feudal dues imposed under seigneurialism, while not applied uniformly across France, were nevertheless unpopular. This is reflected in the cahiers de doléance drafted by the Third Estate in early 1789.

Citation information

Title: ‘Seigneuralism’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/seigneurialism/

Date published: September 18, 2019

Date updated: November 6, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.