The Great Fear (in French, Grande Peur) was a wave of peasant riots and violence that swept through France in July and August 1789. It was apparently sparked by economic concerns, news of political developments in Paris and rumours of counter-revolutionary attacks. Though historians are divided on how this panic became so widespread, the consequences of the Great Fear are more apparent.

Summary

Already excited by the summer’s political developments in Versailles and in Paris, France’s peasants began hearing rumours about roving bands of hired brigands reportedly rampaging through the countryside, raiding villages and stealing grain.

These rumours appeared in different places, took different forms and invoked different levels of response. Many peasants responded by arming themselves and mobilising to defend their property. Some went further and engaged in revolutionary violence, taking to the road, looting the châteaux of landed aristocrats and destroying feudal contracts. The peasants, it seems, became the destructive brigands they had initially feared.

While few people were killed during the Great Fear, property worth millions of livres was either stolen or destroyed.

Peasant xenophobia

The context for the Great Fear was rural paranoia about outsiders. French peasants were accustomed to strangers arriving in their region, usually in the middle of the year when good weather made travel easier. Some of these travellers were landless labourers or destitute townspeople in search of paid work. Others were beggars, vagrants and outcasts who decided that living off the land or seeking the charity of farmers was better than starving in the cities.

Peasant communities were, by their nature, insular and suspicious of outsiders. They considered these strangers with a suspicious eye. New arrivals competed for labour, food and charity provided by the local parish.

The situation was particularly critical in the spring of 1789, as France endured its worst food crisis in years. Even the small stores of grain retained by peasants for their own survival were dwindling. According to John Albert White, who translated Georges Lefebvre‘s pivotal study of the Great Fear, the numbers of itinerants in rural areas reached levels never seen before:

“Unemployed workers, displaced by the crisis in industry, were everywhere in search of jobs… Vagrants and beggars, always a source of concern to the small rural proprietor, choked the roads and threatened reprisals against householders who refused to give them shelter or a crust of bread. Hungry men and women invaded forests and fields and stripped them of firewood or grain, before the harvest was ripe to the gathered.”

News and rumours

Peasant communities were also unsettled by the political events of 1788-89. The convocation of the Estates General and the drafting of the cahiers created a mood of optimism and expectation across the country. The process of writing the cahiers had brought peasants together to discuss their situation and share their grievances, particularly the burdens of royal taxes and feudal dues.

News of the formation of the National Assembly, the Tennis Court Oath and the king’s acceptance of reform caused excitement in peasant communities – but this excitement was short-lived. In mid-July, news reached the provinces that the king had mobilised his troops and sacked his director of finance, Jacques Necker. This sparked rumours and conspiracy theories that a royalist or aristocratic counter-revolution was imminent.

These stories took different forms in different regions. The most common rumour was that the king or his conservative nobles had employed bands of foreign troops or brigands to march into the provinces and bring the people to their knees with violence, looting and wanton destruction.

‘Fear breeds fear’

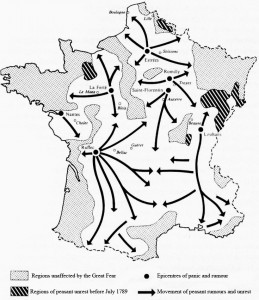

These fears of royal and aristocratic retribution spread exponentially in late July (as Lefebvre himself put it, “fear bred fear”). Lefebvre and later historians have attempted to track the course of the Great Fear, though with limited success.

The circulation of rumour was fast – almost too fast for the age – and sporadic. It did not always follow logical transport routes, such as rivers and roads. There are accounts of the same rumour appearing in places 20 miles apart on the same day. As these rumours circulated, some peasant communities became convinced that hired brigands were marching toward their village.

In this paranoid climate, even the most benign event (a sighting of strangers, movement in the distance, smoke on the horizon) could trigger a panicked response. In Angoulême, for example, thousands of men were armed and mobilised after spotting a cloud of raised dust. A peasant militia in Champagne was raised after locals saw men sneaking through a nearby wood; the ‘invaders’ turned out to be cows.

“The political crisis played an important part, for the excitement it provoked made the people restless and unruly. Every beggar, vagrant and rioter seemed a ‘brigand’. There had always been great anxiety at harvest time: it was a moment the peasants dreaded… The uprising in Paris… spread the fear of brigands far and wide, and at the same time the people anxiously waited for the defeated aristocrats to take their revenge on the Third Estate with the aid of foreign troops. No one doubted for a moment that they had taken the promised brigands into their pay.”

Georges Lefebvre, historian

Destroying feudal records

In some villages or small towns, the Great Fear had a measure of organisation and leadership. Locals gathered on the village green or square to hear from their local representatives. Some resolved to make a preemptive strike against potential counter-revolutionaries. Large bands of peasants, sometimes entire villages, gathered up arms and hit the road in search of targets.

Their violence was not indiscriminate (they targeted only the symbols of feudal authority) nor was it bloodthirsty (fewer than 20 people were reported killed during the panic of July-August). The damage to private property, however, was extensive. The landed aristocracy and seigneurs suffered worse. Their châteaux (country homes) were besieged, invaded, looted and, in most cases, set alight.

Written records bearing names, land holdings, feudal contracts and obligations were eagerly sought and, if found, promptly destroyed. These might take the form of ledgers showing which peasants were subject to the champart, whose quitrents were due and who owed labour for the corvée. If this sabotage did not kill off seigneurial feudalism, the peasants hoped, it would at least make it unworkable.

Minimal violence against nobles

The worst of the Great Fear riots broke out in Dauphiné, south-eastern France, in late July. Beginning in Bourgoin, gangs of peasants engaged in a five-day orgy of destruction, ransacking and burning numerous châteaux until they were dispersed by volunteer soldiers from Lyons and Grenoble.

The nobles themselves were not harmed – unless they tried to resist. Lefebvre reports only three murders during the Great Fear. One of the victims was Michel de Montesson, a nobleman from Douillet who weeks before had sat with the Second Estate at Versailles. Another killed by the mob was Cureau, who had a reputation for hoarding food.

Scores of nobles, however, were chased out of their homes, if not the district. There were instances of aristocrats being held to ransom and forced to renounce their feudal rights over peasants on the estate.

Some nobles were themselves taken in by rumours of roaming brigands. At Limousin in central France, Baron de Drouhet and Baron de Belinay gathered a militia to protect the citizens of Saint-Angel from a rumoured attack. Unfortunately for both barons, guards at Saint-Angel mistook them for spies, and they were bound, gagged and transported by cart to Limoges.

The ergot theory

The Great Fear was a peculiar uprising in that it was spontaneous, sporadic and disorganised. Historians have not yet presented a full or convincing account of what drove the panic of July and August 1789.

One theory, advanced by Mary Matossian in the late 1980s but disregarded by most historians, was that riotous peasants had eaten stored flour contaminated with ergot. The ergot fungus contains lysergic acid, the active compound in the narcotic LSD, and if eaten in sufficient quantities can cause hallucinations and paranoid delusions.

Whatever its true causes, the Great Fear had three significant outcomes. First, it showed that the peasantry in France was prepared to mobilise, take up arms and defend itself. Second, it was destructive and eradicated many aspects of an already weakening seigneurial system. Third, the Great Fear sent a clear message to members of the National Constituent Assembly about the depth of peasant hatred of seigneurialism and feudal dues.

1. The Great Fear (Grande Peur) was a brief but intense wave of peasant riots and uprisings in July and August 1789, triggered by political unrest, rumour and panic.

2. The context for this panic was the economic suffering of mid-1789, the political developments at Versailles and the peasantry’s long-standing fear and suspicion of outsiders.

3. In mid-July, peasants heard rumours that the king and/or his aristocrats had hired gangs of mercenaries or brigands to destroy their crops or property, as a means of imposing political control.

4. They took up arms and mobilise to defend themselves. Some went on long marches, attacking the châteaux of nobles, looting, burning and destroying feudal records.

5. The Great Fear not only exposed the depth of peasant feeling about feudal dues, it caused some consternation among the Second Estate and the deputies of the National Constituent Assembly.

Perigny on the Great Fear peasant uprisings (1789)

Citation information

Title: ‘The Great Fear’‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/great-fear/

Date published: October 7, 2019

Date updated: November 9, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.