The Constitution of 1791 was the first of several attempts to create a written constitution for France. Inspired by Enlightenment theories and foreign political systems, it was drafted by a committee of the National Assembly, a group of moderates who hoped to create a better form of royal government rather than something radically new. By the time it was adopted in the autumn of 1791, however, the new constitution was already outdated, overtaken by events of the revolution and growing political radicalism.

Why a constitution?

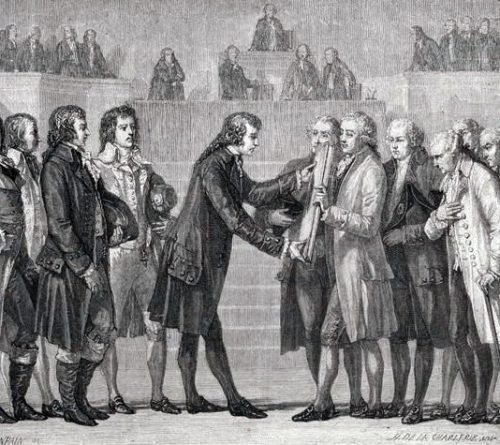

On June 20th 1789, the newly formed National Assembly assembled in a Versailles tennis court and pledged not to disband until France had a working constitution.

The deputies of the Third Estate believed any reforms to the French state must be outlined in and guaranteed by a written constitution. Such a document would become the fundamental law of the nation, both defining and limiting the power of the government, and protecting the rights of citizens.

Fascination with constitutions and constitutional government was a creature of the Enlightenment. Before the 18th century, monarchical and absolutist governments had acted without any form of written constitution. The structures and power of government were shaped and limited by internal forces and events – if they were limited at all.

The British example

Political theorists looked at systems abroad for examples. Nearby Britain had no written constitution but the power of the British monarchy had been constrained by Britain’s nobility, its parliament, the Civil War (1642-51), the Glorious Revolution (1688) and other factors. Over time, the British system embraced a balance of power between the monarch, the parliament, the aristocracy and the judiciary.

The idea that political power would sort itself out over time was not acceptable to Enlightenment philosophers. Men like John Locke, Baron de Montesquieu and Thomas Paine believed that government must be founded on rational principles and organised in a way that best serves the people.

The best device for ensuring this was a written constitution: a foundational law that defines the structures and powers of government, as well as rules and instructions for its operation.

The American example

The French revolutionaries also had a recent working model of a national constitution. The United States Constitution had been drafted in 1787 and ratified by the American states the following year, in the wake of the American Revolution.

The American constitution embraced and codified several Enlightenment ideas, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau‘s popular sovereignty and Montesquieu’s separation of powers. As the French were deliberating on their own constitution, the Americans were also finalising the inclusion of a bill of rights into theirs.

There was one significant difference between the two systems, however: the American constitution established a republican political system with an elected president as its chief executive, rather than a monarch.

Challenges of a constitutional monarchy

In France, the National Constituent Assembly remained wedded to the idea of a constitutional monarchy. The Assembly wanted to retain the king but to ensure that his executive power was subordinate to both the law and the public good.

This presented the Assembly with two concerns. First, they had to find a constitutional role for the king and determine what political powers, if any, he should retain. Would he remain an active participant in the new system, with the power to appoint ministers, access spending and initiate or block laws? Or would the king simply be a figurehead?

Second, a constitutional monarchy would be entirely dependent on having a king loyal to the constitution. In the months that followed, the king’s lack of interest in constitutional government would cause problems for the new regime.

Drafting a constitution

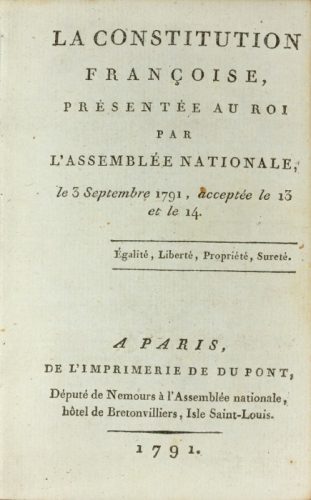

Preparation and drafting of the constitution began on July 6th 1789, when the National Constituent Assembly appointed a preliminary constitutional committee. This committee was made permanent and expanded to 12 men on July 14th, the day of the Bastille raid, though the two events were unrelated.

Among the members of the constitutional committee were Charles de Talleyrand, Bishop of Autun; the radical Bretonist Isaac le Chapelier; the conservative lawyer Jean-Joseph Mounier; and Emmanuel Sieyès, author of What is the Third Estate?

Almost immediately, the constitutional committee cleaved into two factions. One faction favoured a bicameral (double chamber) legislature and the retention of strong executive powers for the king, including an absolute veto. This group, which included Mounier and the Marquis de Lafayette, was dubbed the Monarchiens or ‘English faction’.

A second group wanted a strong unicameral (single chamber) legislature and a monarchy with very limited power. This group, led by Sieyès and Talleyrand, won the day in the National Constituent Assembly.

The issue of voting rights

By October 1789, the committee was wrestling with questions of franchise: exactly who would have the right to vote to elect the government?

Eventually, the committee decided to separate the population into two classes: ‘active citizens’ (those entitled to vote and stand for office) and ‘passive citizens’ (those who were not). ‘Active citizens’ were males over the age of 25 who paid annual taxes equivalent to at least three days’ wages. This was, in effect, a property qualification on voting rights.

In today’s world, where universal suffrage is the norm, this seems grossly unfair – but property restrictions on voting were quite common in 18th-century Europe. Voting was not a natural right conferred on all: it was a privilege available to those who owned property and paid tax. By way of comparison, England in 1780 was a nation of around eight million people yet only 214,000 people were eligible to vote.

The National Constituent Assembly’s property qualifications were considerably more generous than that. They would have extended voting rights to around 4.3 million Frenchmen. Despite this, radicals in the political clubs and sections demanded that voting rights be granted to all men, regardless of earnings or property.

The king’s new powers

The other feature of the Constitution of 1791 was the revised role of the king. The constitution amended Louis XVI’s title from ‘King of France’ to ‘King of the French’. This implied that the king’s power emanated from the people and the law, not from divine right or national sovereignty. The king was granted a civil list (public finding) of 25 million livres, a reduction of around 20 million livres on his spending before the revolution.

In terms of executive power, the king retained the right to form a cabinet and to select and appoint ministers. A more pressing question was whether he would have the power to block laws passed by the legislature. Again, this was resolved with debate and compromise.

The Monarchiens, most notably Honore Mirabeau, argued for the king to be granted an absolute veto, the executive right to block any legislation. Democratic deputies argued for a more limited veto, and some for no veto at all.

It was eventually decided to give the king a suspensive veto. He could deny assent to bills and withhold this assent for up to five years. After this time, if assent had not been granted by the king, the Assembly could enact the bill without his approval.

“When the Constitution of 1791 was finally adopted, it embodied a fundamental contradiction and a recipe for constitutional impasse. To safeguard national sovereignty from the dangers of representation it permitted the monarch to veto legislative decrees – and hence paralyse the Assembly… As a result of the veto the Constitution of 1791, as Brissot remarked, could only function under a ‘revolutionary king’… Once it appeared, in the spring of 1792, that Louis XVI’s exercise of the veto was frustrating rather than upholding the will of the nation, the monarch and the Constitution itself were under siege.”

Keith M. Baker, historian

The constitution undermined

Even as the constitution was being finalised, any hopes for its success were being overtaken by other events. In June 1791, the king and his family stole away from the Tuileries and fled Paris. They were detained at Varennes the following morning.

The king’s attempt to escape Paris and the revolution brought anti-royalist and republican sentiment to the boil. The National Constituent Assembly tried riding out the storm by claiming the royal family had been abducted and reinstating the king – but the Cordeliers, the radical Jacobins and the sans-culottes of Paris were not buying it.

The Constitution of 1791 was passed in September but had already been fatally compromised by the king’s betrayal. France now had a constitutional monarchy but the monarch, by his actions, had shown no faith in the constitution.

In a conversation with the conservative politician Bertrand de Molleville, Louis XVI suggested that he would bring about change by making the new constitution unworkable:

“I am far from regarding the constitution as a masterpiece. I think it has a great many defects. If I had been permitted to make some observations, some useful changes might have been made. But it is too late for that now. I have sworn to maintain the constitution, wars and all, and I am determined to keep my oath. It is my opinion that that execution of the constitution is the best way of making the people see the changes that are necessary.”

1. The Constitution of 1791 was drafted by the National Constituent Assembly and passed in September 1791. It was France’s first attempt at a written national constitution.

2. The Assembly delegated the task of drafting the constitution to a special constitutional committee. It began in July 1789 by debating the structure the new political system should have.

3. The Assembly eventually concluded that France should be a constitutional monarchy with a unicameral (one house) legislature. Voting rights were restricted to ‘active citizens’, i.e. those who paid a minimum amount of taxation.

4. The constitution retitled Louis XVI as “King of the French”, granted him a reduced civil list, allowed him to select and appoint ministers and gave him a suspensive veto power.

5. The king’s flight to Varennes in June 1791 rendered the Constitution of 1791, and thus the constitutional monarchy, unworkable. It also fuelled a spike in Republican sentiment in Paris.

Citation information

Title: ‘The Constitution of 1791’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/constitution-of-1791/

Date published: September 16, 2019

Date updated: November 11, 2023

Date accessed: July 26, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.