August 4th 1789 was a historic journee of the French Revolution. On this date, deputies of the National Constituent Assembly, responding to a wave of peasant unrest and destruction, legislated to abolish feudal seigneurialism across the nation. These sweeping changes went too far for some but not far enough for others. They were met with joyous optimism – but also concern that the rural structures of the old regime had been turned upside down.

The famous night sitting

Sitting into the night and the early hours of the following day, the deputies of the National Assembly rose one by one to surrender their privileges and feudal rights. In the days that followed. they drafted, debated and passed 19 decrees codifying these promises.

The August Degrees, as they became known, have often been described in optimistic terms. The events of August 4th have been portrayed as the pinnacle of the revolution, a surge of patriotic self-sacrifice, the last noble act of the nobility.

Digging deeper uncovers more practical reasons for the reforms of August 1789. In addition, the grand promises made on the night of August 4th and passed into law in the August Decrees did not go as far as many believed or hoped for.

Context and inspiration

The context for the Assembly’s August 4th reforms was a disconnected but widespread series of peasant uprisings that broke out across France in mid-1789.

From late July, thousands of peasants had run amok in the countryside, disrupting work, intimidating property owners and causing some damage. In the worst cases, peasants assaulted or chased away the owners of seigneurial rights, seized and burned feudal records and burned down chateaux owned by noblemen. For the most part, these unruly mobs were inspired by rumours that royalist bandits or mercenaries were sweeping the countryside.

The weeks of revolt and destruction in rural areas that followed became known as the Great Fear (French, Grande Peur).

A plan to quell unrest

News of this rural violence electrified discussions in the Assembly. The majority of deputies, predominately members of the bourgeoisie and liberal nobility, were concerned that the Great Fear might spread further and threaten property rights.

With no means of suppressing the peasants by force, the Assembly’s only avenue was to pacify them. Liberal deputies from the Breton Club (the forerunner to the Jacobin movement) believed the peasants could only be calmed by a grand gesture from the Assembly, such as a partial surrender of feudal rights.

In the first days of August, the Bretons planned to rise in the Assembly and renounce certain feudal dues. This task was assigned to the Duke of Aiguillon, a radical nobleman, and Viscount de Noailles, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War.

‘Patriotic delirium’

The Assembly opened its August 4th session at 8pm, first by hearing a draft proclamation for the restoration of public order. The Breton Club deputies then initiated their plan, calling for the abolition of feudalism.

Their plan for a controlled surrender of feudal rights soon went awry, as the session was overcome by what has been described as “patriotic delirium”, “effervescence”, “the abandonment of restraint and sense” and “an orgy of self-sacrifice”.

Inflated with liberal idealism and overcome by the moment, many deputies went further than they had originally intended. One after the other, as if to outdo each other, deputies of the Second Estate stood and renounced their feudal rights. All manner of feudal dues were voluntarily surrendered: from seigneurial courts to pluralities, from game laws to the lord’s right to the first harvest. The venal sale of public offices was abolished; so too were noble privileges and exemptions unconnected with seigneurial dues.

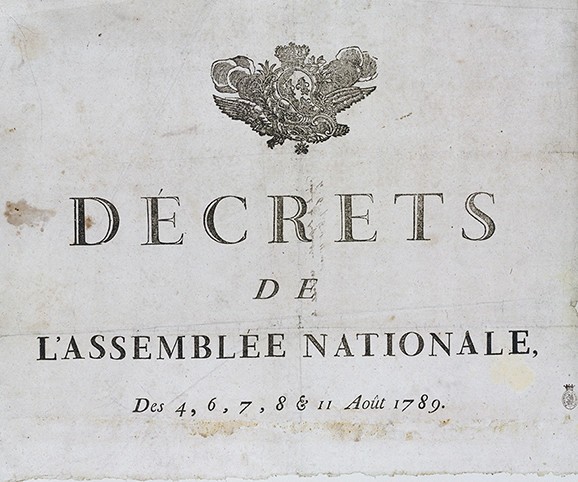

In the days that followed, the Assembly passed 19 decrees that codified the idealistic changes made on the night of August 4th.

Public adoration

The response from the revolutionaries was as euphoric as the mood in the Assembly on August 4th. Paris mayor Jean-Sylvain Bailly declared that “the National Assembly achieved more for the people in a few hours than the wisest and most enlightened nations had done for many centuries”.

The August Decrees created fundamental change across the breadth of the nation. They stripped away the domination and privilege of the nobility, creating a society based on individualism, equality and merit. The abolition of the tithe halved the income of the Church. The peasantry, previously kept at arm’s length from the revolution, was now part of it.

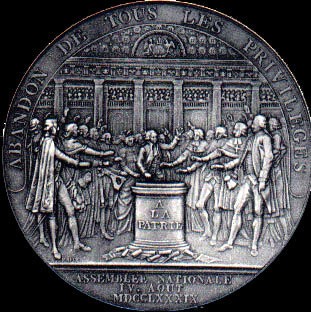

The Assembly’s deputies were hailed as heroes and praised for their self-sacrifice. Works of art were produced and medallions struck to commemorate the event.

Scepticism

Others were more sceptical and suggested the Assembly had gone too far too quickly. Centuries-old institutions, procedures and traditional relationships had been disposed of spontaneously in just a few hours, with only vague ideas about what might replace them.

Ancien Régime feudalism, for all its confusion and inconsistency, had provided a basis for French society, agricultural production and land management. Privilege, for all its inequality, had underpinned France’s political, judicial and administrative systems. The Assembly’s abolition of this framework meant it would need to be replaced – a long and difficult process for any government, let alone one in the throes of revolution.

There was also the question of how seigneurial rights holders might respond to ideologues in the Assembly legislating away their property. Many believed the monarchy, nobility and high clergy might organise a counter-revolution to recover what they had lost.

“It is quite true that the abolition of ‘the general effects of the feudal system’… along with the various judicial and administrative reforms, entailed the destruction of seigneurial power and laid the foundations of a unified national state. But the terms of redemption turned the abolition into a compromise heavily weighted in favour of the aristocracy. In the end, the real cost was to be borne by the tenant-farmers and share-croppers. For although the peasants had been freed from the feudal system, they did not all benefit equally from their new liberty.”

Alfred Soboul, historian

Implications

News of the August Decrees had some immediate practical effects. At first, France’s peasants welcomed the decrees, seeing them as a fulfilment of peasant grievances expressed in the cahiers.

Many peasants, however, were frustrated that the August reforms did not go far enough. The champart, one of the most despised feudal dues, was not abolished in August 1789 because the Assembly considered it private property. These dues could not be abolished until the owner was first compensated, something beyond the reach of almost all peasants.

After August 4th, many peasants refused to pay any feudal dues, taxes and tithes – including some not specifically abolished by the decrees.

The August Decrees caused the Great Fear to dissipate as a movement but peasant unrest and violence continued into late 1789 and early 1790. It would not end until the Assembly abolished all dues without compensation in April 1790.

1. The August 4th session of the National Constituent Assembly was a historic event that produced radical changes, most notably the abolition of French feudalism or seigneurialism.

2. This session was held at the time of the Great Fear peasant uprisings. Breton Club liberals in the Assembly proposed a series of reforms or concessions to pacify the peasants.

3. The reforms went much further than intended, with the August 4th session transforming into a night where noble deputies voluntarily surrendered their privileges and feudal rights.

4. The Assembly then passed the August Decrees, formalising the abolition of seigneurial feudalism and noble privilege in France. It was welcomed and celebrated by liberal revolutionaries.

5. The peasants, however, were only temporarily pacified by the August Decrees. Many feudal rights could only be abolished if the owner was compensated, something the peasants could not deliver.

Citation information

Title: ‘The August 4th Decrees’‘

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/august-4th-decrees/

Date published: October 19, 2019

Date updated: November 9, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.