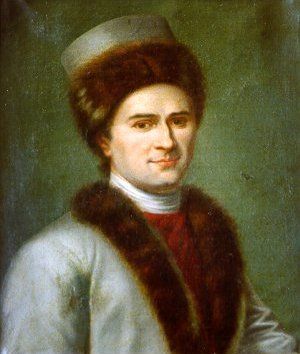

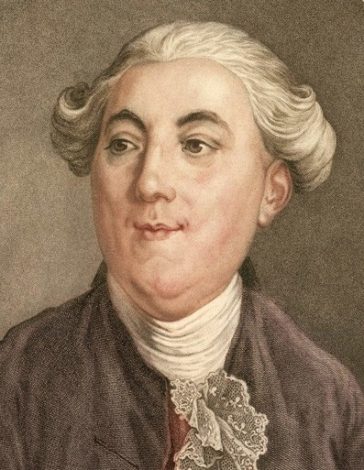

In October 1776 Louis XVI placed responsibility for the national finances in the hands of Swiss financier Jacques Necker (1732-1804). Necker’s four-year tenure had a significant impact on the French national economy, in part because of his reliance on foreign loans and the deceptive financial reporting he used in his 1781 Le Compte Rendu.

A curious choice

Necker was a curious choice for such an important office in the French royal government. He was not a native Frenchman but was instead born and raised in Switzerland to a family of English heritage. Unlike his predecessors, he held no noble or clerical title.

Necker was Protestant rather than Catholic. This fact alone prevented him from being appointed comptroller-general, forcing the king to create a new office. Necker had no background in ministerial government or public office.

Despite all this, Necker was well equipped for the role – and indeed, certainly better qualified than some who had previously held it. He had shown considerable skill in business, making his name and fortune as a banker, financier and director of the French East India Company. He had also published essays on France’s national economy and was an outspoken critic of Anne-Robert Turgot‘s fiscal reforms.

Reaction to Necker’s appointment

Necker’s elevation was popular both with the local financial community and observers outside France. The value of royal bonds rose significantly after his appointment, as did some share prices. An Italian report praised Necker’s early policies, declaring that he had “made his superior abilities known through several works of truly sublime talent, lacking in partiality and filled with vast and excellent information about the finances”.

Necker certainly initiated some successful, albeit minor economic reforms. He targeted the notorious Ferme Générale, the oligarchy of ‘tax farmers’ contracted by the government, ordering a reduction in their number and placing some of their activities under state supervision. He also abolished numerous sinecures and negotiated reductions in royal spending.

These minor reforms produced a small but noticeable increase in government revenue, which rose from around 25 million livres to 30 million livres during Necker’s five years in office.

A master of credit raising

Necker’s true financial skill, however, was both the acquisition and the juggling of credit. Between late 1776 and his resignation in 1781, he signed off on a series of new or revised loans on behalf of the French government. Most were obtained through bankers in his native Geneva. Though the true value of these loans is difficult to calculate, it is believed he borrowed in the region of 530 million livres in his four and a half years in office.

Necker used these loans to finance the state, to create the illusion of a recovering economy and, perhaps, to maintain his personal reputation. Unfortunately, this access to easy money gave the king and his ministerial advisors an unwarranted confidence in the nation’s economy.

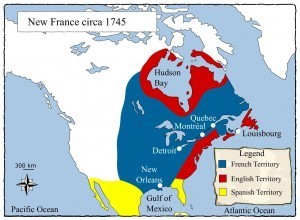

Not fully aware of the parlous state of the national finances, Louis XVI committed his support for the American Revolution – first with material aid for the rebellious American colonists, then with a declaration of war against Great Britain in March 1778. France’s involvement in the American Revolutionary War would cost the nation close to two billion livres. Necker was able to fund the war effort but again, this was mostly achieved with new and renegotiated loans.

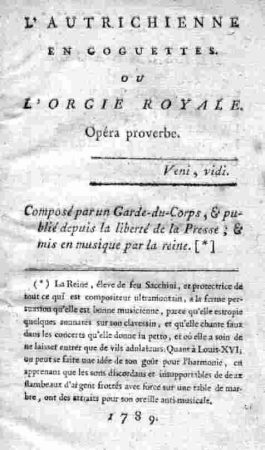

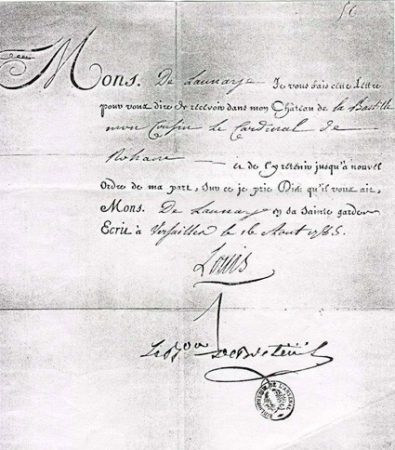

Le Compte Rendu

By no means did Necker fool everyone. He had plenty of enemies in the royal court and by 1780, some writers and cartoonists were ridiculing his smoke-and-mirrors approach to fiscal management.

In January 1781, Necker responded to these criticisms by publishing Le Compte Rendu au Roi (‘The Record of Accounts for the King’). For the first time in France’s history, the general public was presented with a full and frank account of the nation’s finances.

Sadly, both for the people and the king, the Compte Rendu was little more than a gigantic con, an exercise in public deceit through false accounting. By cooking the books, overestimating revenue and omitting significant expenses such as war costs, Necker was able to forecast an annual surplus of 12 million livres, based on revenue of 264 million livres and expenditure of 254 million. The true state of the nation, later calculated by Necker’s successors, was a 70 million livre deficit.

Necker’s popularity

The Compte Rendu drove Necker’s popularity to new heights. For the first time in history, an agent of the French royal government had taken the people into his trust and raised the veil of secrecy over the nation’s finances. The Compte Rendu sold thousands of copies and Necker was hailed as both a liberal political reformer and a clever economic manager, even though experts quickly picked up on his deceptive accounting.

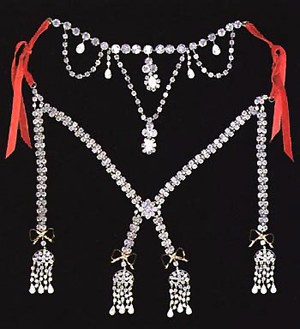

Conservatives in the royal court – including foreign minister Comte de Vergennes, Marie Antoinette and the king himself – were appalled at Necker’s publication of the national balance sheet. In their view, the ordinary citizen had no need to know the state of the nation’s finances. To involve the public in such matters was not only presumptuous, it undermined the principles of absolutist monarchy.

In May 1781, five months after the publication of the Compte Rendu, Louis XVI asked Necker for his resignation.

“The public nature of the Compte Rendu, rather than its inaccuracy, incensed ministers. Necker was accused of being something less than a Frenchman. Vergennes gave to Louis XVI an opinion of the Compute Rendu which encapsulated this point of view: ‘…the example of England, where accounts are made public, is that of a calculating, selfish, troublesome nation. To apply such principles to France is a national insult: we are people of feeling, trusting and devoted to the person of the King’, and he went on to spell out that the Compte Rendu was a slight to monarchy… The King yielded and Necker lost office.”

Olwen Hufton, historian

Dismissal and replacement

Necker was replaced by Joseph Joley de Fleury, a conservative and uninspiring magistrate from the Paris parlement. Joley de Fleury found himself having to juggle expensive loans and mounting war debts. He resorted to the old methods of revenue raising: a new vingtième, the sale of venal offices and more loans. Joley de Fleury resigned after less than two years, while his replacement Henry Lefevre d’Ormesson lasted just a few months.

In November 1783, the king appointed Charles de Calonne, one of the critics of Necker and his Compte Rendu, as controller-general of finances. Calonne immediately recognised the dire financial state of the nation. Rather than raise taxes, he decided to stimulate the economy with several large spending projects, funded by more loans.

Calonne’s policies raised the suspicion of the Paris parlement which, by 1785, was threatening to deny registration to further loan contracts. This not only brought the king into confrontation with the parlements, it also forced Calonne to embrace fiscal reform as his only course of action.

By 1786, France’s national spending was outstripping its income by 161 million livres, or 34 percent, while interest on loans made up more than 40 percent of the government’s outlays:

Government revenue in 1786 (livres):

Indirect taxes – 219.5 million

Direct taxes – 162.8 million

Royal lands and forests – 51.9 million

Royal monopolies – 18.8 million

Donations – 18.8 million

Total – 472 millionGovernment expenditure in 1786 (livres):

Interest on debt – 259.5 million

Military spending – 158.3 million

Costs and expenses – 66.5 million

Salaries and pensions – 50.6 million

Royal household – 44.3 million

Charitable spending – 19 million

Public works – 12.7 million

Foreign affairs – 12.6 million

Total – 633 million livres

1. Jacques Necker was a banker and company manager who was handed responsibility for France’s national treasury in 1776, despite being a commoner, a Protestant and of Swiss birth.

2. In his more than four in this role, Necker undertook some minor reforms that increased revenue – but he also increased the nation’s debt by signing off on around 530 million livres in new and renegotiated loans.

3. In January 1781, Necker sought public support by publishing Le Compte Rendu, a balance sheet of the national finances, the first time information of this kind had been publicly released.

4. Through deceptive accounting, the Compte Rendu claimed the nation was in good financial shape and was likely to record a surplus when the reality was closer to a 70 million livre deficit.

5. Publishing the national accounts increased Necker’s public popularity – but it brought him into disrepute with the king and the royal court. Necker was sacked in May 1781, leaving his successors with greatly inflated levels of national debt.

Extracts from Jacques Necker’s Compte Rendu (1781)

Citation information

Title: ‘Jacques Necker and the Compte Rendu’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/jacques-necker-compte-rendu/

Date published: September 21, 2019

Date updated: November 8, 2023

Date accessed: May 17, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.