The works of Enlightenment theorists were not the only publications to arouse revolutionary sentiment in France. In the 1780s, French cities were also awash with a much more crude form of literature called libelles. Taking various forms and ranging from political fiction to outright pornography, these libelles attacked royals, nobles and politicians, undermining their status and authority in the old regime.

What were libelles?

Usually printed as short stories, plays or pamphlets, libelles contained vulgar and defamatory stories about public figures. There was seldom any truth to these stories, though that did not discourage either their publishers or their readers, who were predominately from the lower classes.

Libelles could target anyone of note but most honed in on royals, aristocrats and political figures. By 1789, however, the most common target was Marie Antoinette. The French queen was subject to a torrent of vile and slanderous pornography, most accusing her of outrageous and disgusting behaviour.

According to Robert Darnton, a historian and researcher of the libelles, the “avalanche of defamation” levelled at Marie Antoinette from 1789 to her execution in 1793 has “no parallel in the history of vilification”.

An old form of propaganda

The use of crude humour and pornographic satire for political purposes dates back to ancient times. Leaders and powerful figures have often been subjected to ridicule based on their appearance, personal habits and sexual proclivities.

Women have not been exempt from this, and in some cases they have suffered worse than men. Russia’s Empress Catherine the Great (1729-1796), for example, was frequently portrayed as having an insatiable carnal appetite, bordering on nymphomania and debauchery. This campaign continued after Catherine’s death which, according to popular rumour, was caused by an act of sexual congress with a horse.

Pornographic libelles in France circulated misogynistic fantasies that were no less outrageous. In the six months preceding the revolution, most political pornography honed in on Marie Antoinette. The queen – being female, of foreign birth, fond of fashion, slow to deliver a royal heir and famously strong-willed – was an easy target for satirists and pornographers. Attacking Antoinette was also a means of attacking the king, without doing so directly.

Forms of libelle

Libelles came in a range of literary forms. They could be fliers or broadsheets, pamphlets, dramatic scripts, essays or collections of cartoons. The only common trait was that their content was slanderous and offensive.

The more serious libelles took the form of essays that often presented as serious and legitimate journalism. These publications would promise to provide the ‘true story’ behind the crown, the royal family, notable aristocratic families or the goings-on at Versailles.

Many of these texts cited a newly acquired cache of letters or ‘court insiders’ (never named, of course) as the source of their information. In reality, many libelles simply repeated gossip of the day, embellished with a considerable amount of creative licence and flair.

It is not surprising that this kind of gossip flourished. Unlike modern royals, who are known to us through media saturation, the French public knew little about the people who ruled them. There was almost no public reporting on the royal family, government or Versailles. This dearth of information was eagerly filled by the rumour mongers and the gutter press.

Attempts at suppression

Inside France, state censorship and the use of lettres de cachet made publishing defamatory material a dangerous activity. The noted revolutionary Honore Mirabeau, for example, spent almost a year behind bars for writing a lukewarm satire about a powerful nobleman.

Because of these dangers, the majority of libelles were published outside France and smuggled into the country. Several French libellistes were based in London, where publishing laws were more liberal and publishers could operate beyond the reach of the French government.

Most London-based French libellistes rented rooms and printing presses on Grub Street, a notorious haunt for struggling writers, gutter journalists and smut pedlars. These expatriate publishers were sometimes referred to as Rousseaus du ruisseau (‘Rousseaus of the gutter’).

Most libellistes were more interested in making money than inciting revolution. Some libelles generated more incoming from blackmail than sales. The ‘victim’ of a new libelle was sometimes approached with the document with demands for a cash payment to prevent copies being distributed. Some found it easier to pay the ransom than deal with a firestorm of gossip.

Charles de Morande

One of the most notorious French libellistes – certainly one of the most skilled – was Charles de Morande (1741-1805). Morande’s Gazetier Cuirassé (‘Battleship Gazette’, published 1771) was a racy account of the court and government of Louis XV.

In it, Morande took particular aim at the king, his mistress Madame du Barry, the king’s chancellor René de Maupeou and his minister of state, the Duke of Vrillière. Like several of Morande’s other libelles, it contained pornographic gossip accompanied by political criticism, amateur philosophy, accusations of incompetence and stories of alleged corruption.

Morande broke new ground by attacking women as vociferously as men, perhaps more so. The wife of one French aristocrat, he alleged, frequently had sex with the butler below stairs. A group of noble ladies caught syphilis from their toy boys, Morande claimed, and the disease had caused their teeth and eyebrows to fall out.

Only a small number of these libelles were actively distributed in French cities – but those that did were wildly popular. The ordinary sans-culotte had trouble digesting Diderot or making sense of Rousseau – but when political criticism and philosophy were kept simple and accompanied with smut, he found it much more acceptable.

The campaign against Antoinette

The volume and pornographic intensity of the libelles increased after the outbreak of revolution in 1789. Much more than before, this material honed in on the king and queen. Darnton estimates that before 1789 only about 10 percent of pornographic libelles targeted Marie Antoinette. From early 1789, however, the vast majority of these publications took aim at the queen.

Antoinette had always been a figure of ridicule. The gutter press had long before dubbed her l’Autrichienne (literally ‘the Austrian woman’ but doubly interpreted as ‘the Austrian bitch’, chienne being French for a female dog).

The queen was depicted as having an insatiable sexual appetite. She needed constant satisfaction, it was claimed, but was unable to obtain this from her husband, who was either disinterested, impotent or inadequately endowed. According to libelles, the nymphomaniacal but frustrated Antoinette sought sexual favours from her brother-in-law, from various court nobles, from servants, even from her own children. Stories had her plotting behind the king’s back and taking lovers, sometimes several times a day. Some visual material showed her surrounded by gigantic penises or engaged in acts of tribadism (lesbianism).

“Marie Antoinette occupies a curious place in this literature; she was not only lampooned and demeaned in a ferocious pornographic outpouring, but she was also tried and executed… [While] the king’s trial remained entirely restricted to a consideration of his political crimes… the trial of the queen, especially in its refractions of the pornographic literature, offers a unique and fascinating perspective on the presumptions of the revolutionary political imagination. It makes manifest… the underlying interconnections between pornography and politics.”

Gary Kates, historian

Pornographic themes

One of the earliest libelles against the queen was Essais historiques sur la vie de Marie Antoinette (‘Essays on the private life of Marie Antoinette’). First published in 1781, it reappeared in several forms over the next decade.

This recurring text accused Antoinette of a litany of treacherous and immoral acts, including adultery, dalliances with the king’s own brother, lesbianism, masturbation, wasteful spending for its own sake and political intriguing against the king and the French people. In some 1789 editions, Antoinette was even accused of poisoning the young Dauphin who had died of tuberculosis in June that year.

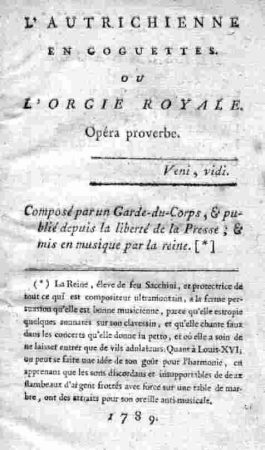

The events of 1789 opened the floodgates for an even greater torrent of hateful and poisonous literature. Le Godmiché Royal (‘The Royal Dildo’) portrays Antoinette as a sexually frustrated user of sex toys. L’Autrichienne en Goguettes ou l’Orgie Royale (‘The Austrian bitch and her Friends in the Royal Orgy’) suggests Antoinette had a string of lovers, including the Duchess of Polignac and the Count of Artois, who was also the true father of her children.

Impact of libelles

The royal government attempted to stamp out these libelles, of course, but their efforts were in vain. In 1783, officials destroyed 534 copies of Essais historiques but as many as 30,000 copies are still believed to have circulated during the 1780s.

To outsiders, this lurid and tawdry political pornography can appear a sideshow to more significant revolutionary ideas. The libelles did not incite revolution themselves: they offered no cogent political criticism of the old order, nor did they outline or advocate changes for the future.

What the libelles did do was reflect and reinforce declining respect and affection for the monarchy. It exacerbated this decline by holding the king and queen up for public ridicule. Moreover, the booming spread of libelles in 1789 was more evidence of Louis XVI‘s incompetence. A king who could not find a way to crush the gutter press – particularly when it smeared his wife – was hardly fit to be king.

1. Libelles were crude, slanderous and usually baseless forms of literature that denigrated and attacked the behaviour of public figures.

2. Many libelles were pornographic in their tone and content. Men and women alike were often targeted and condemned for their sexual behaviour and alleged promiscuity.

3. Most libelles against French figures were produced abroad, chiefly in London’s Grub Street. They were then smuggled into France or used to extract ransoms from their targets.

4. From the spring of 1789, Marie Antoinette became a regular target for libelles, which accused her of sexual debauchery, overspending and acts of treachery against the king.

5. While libelles did not advocate revolution or contain much political criticism of the old regime, they undoubtedly eroded public respect and affection for the monarchy.

Document: a libelle about Marie-Antoinette and the King’s brother (late 1780s)

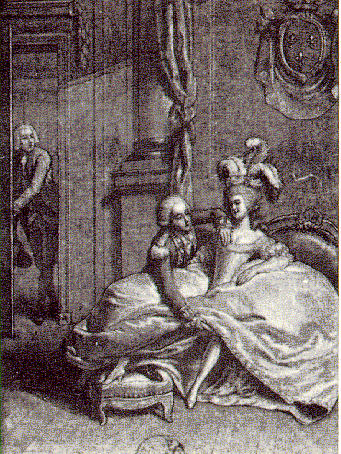

Image: Louis the Cuckold (late 1780s)

Image: Marie-Antoinette’s bedroom (late 1780s)

Citation information

Title: ‘Libelles and political pornography’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/libelles/

Date published: September 21, 2019

Date updated: November 7, 2023

Date accessed: April 23, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.