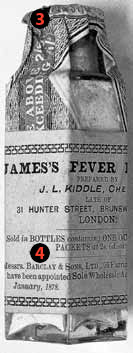

Robert James (1703-1776) was a London physician and author. James was born in Staffordshire and educated at both Oxford and Cambridge. By the mid 1740s James owned a busy medical practice in London. He also established friendships with the literary elite, including John Newbery and Samuel Johnson.

During his career James developed and patented several medicines. His most popular concoction was ‘Fever Powder’, a dangerous mix of antimony and calcium phosphate that was still being sold into the early 20th century. James also penned numerous medical guides, including his three-volume Medical Dictionary and a 1747 guide to medicines called Pharmacopoeia Universalis.

The latter contains a section on the medicinal value of human by-products. One of the most versatile of these, writes James, is dried menstrual blood. Provided it is taken from the first flow of the cycle, menstrual blood can be of great benefit:

“Taken inwardly it is commended for the stone[s] and epilepsy… Externally used it eases the pains of gout… It is also said to be of service for the pestilence, abscesses and carbuncle… [It also] cleans the face from pustules.”

Women enduring a difficult childbirth, writes James, can “facilitate the delivery” by sipping:

“…a draught of the husband’s urine”.

Source: Robert James, Pharmacopoeia Universalis, 1747. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.