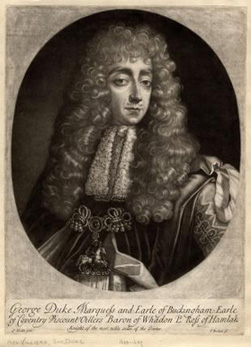

George Villiers (1628-1687) was an English courtier, politician, writer and, later, the second Duke of Buckingham. His father, also George Villiers, was a favourite (and according to some, a bisexual lover) of King James I. Villiers Senior was stabbed to death shortly after the birth of his son, who was then raised in the royal court alongside the future Charles II.

Young George was sent to study at Cambridge but was bored by lectures, being spotted by Thomas Hobbes “at mastrupation, his hand in his codpiece”. Villiers later sided with the Royalists during the English Civil War, joining Charles II in exile. He returned to England in 1657 and participated in the Restoration, serving in Charles’ court and on the Privy Council.

Villiers’ political career was marked by scandals, intrigues and feuds. Two notable incidents were a hair-pulling brawl with the Marquess of Dorchester on the floor of the House of Lords, and a 1668 duel where Villiers shot dead the Earl of Shrewsbury. Villiers had been having an affair with the Countess of Shrewsbury; he later caused public outrage by moving the countess into his own home and living in a virtual menage a trios.

“He told me he was on horseback but two days before… He told me he had a mighty descent [and had] fallen upon his privities, with an inflammation and great swelling. He thought by applying warm medicines the swelling would fall and then he would be at ease. But it proved otherwise, for a mortification came on those parts, which ran up his belly and so mounted, which was the occasion of his death…. I found him there in a most miserable condition.”

Even though he remained conscious and alert, Villiers’ doctors gave him but a day or two to live. They asked Arran to break the news to Villiers, who received it stoically. He deteriorated rapidly and passed away at 11 o’clock the following night.

Villiers was interred in Westminster Abbey, his funeral a somewhat grandiose and overblown affair, given his tumultuous and controversial political career. Having expired without a legitimate heir, Villiers’ title died with him and his estate was broken up and sold. His wife Mary died in 1704 and was interred alongside him in the Abbey. Their graves are presently unmarked.

Source: Letter from Lord Arran to the Bishop of Rochester, April 17th 1687. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.