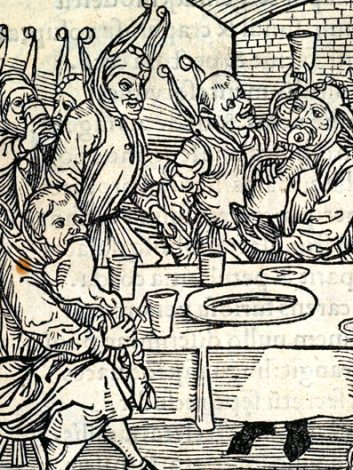

Cat burning was particularly common in France, where a dozen live cats were routinely torched in Paris every Midsummer’s Day (late June). English courtier Philip Sidney attended one of these feline infernos in 1572. In his chronicle Sidney noted that King Charles IX also threw a live fox onto the fire, for added interest. In 1648, France’s King Louis XIV, then aged just 10, lit the tinder on a large bonfire in central Paris, then watched and danced with glee as a basket of stray cats was lowered into the flames. Live cats were frequently burned alive elsewhere in Europe, particularly at Easter or the period around Halloween.

Cat-burning was less common in Britain, though a few examples are recorded. One comes from the letters of Englishman Charles Hatton. In November 1677, Hatton wrote to his brother, chiefly about who might be appointed Archbishop of Canterbury. He closed his letter by describing a recent celebration to mark the 119th anniversary of Elizabeth I taking the throne.

At the centre of this pageantry, Hatton wrote, was a large wickerwork figure of Pope Innocent XI, an effigy that reportedly cost £40 to make. The wicker pope was paraded through London, then erected in Smithfield and set alight. Inside its baskety innards was a number of live cats:

“Last Saturday the coronation of Queen Elizabeth was solemnised in the city with mighty bonfires and the burning of a most costly pope, carried by four persons in diverse clothing, and the effigies of devils whispering in his ears, his belly filled full of live cats, who squawled most hideously as soon as they felt the fire. The common saying all the while was [the cats’ screeching] was the language of the Pope and the Devil in a dialogue between them.”

According to Charles Hatton, these perverse celebrations were concluded with the opening and distribution of a free barrel of claret.

Source: Letter from Charles Hatton to Christopher Hatton, November 22nd 1677. From Correspondence of the Family of Hatton, vol. 1, 1878. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.