Source: The Minneapolis Journal, October 4th 1906. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.

Category Archives: Death

1796: Rhode Islanders ward off disease with corpse-burning

“[Staples] prayed that he might have liberty granted unto him to dig up the body of his daughter, Abigail Staples, late of Cumberland… in order to try an experiment on Livina Chace, wife of Stephen Chace… sister to the said Abigail… which being duly considered it is voted and resolved that the said Stephen Staples have liberty to dig up the body of the said Abigail, deceased, and after trying the experiment as aforesaid that he bury the body of the said Abigail in a decent manner.”

The ‘experiment’ Staples had in mind involved burning his daughter’s body in the presence of Livina Chace and other family members, so they might stand in and inhale the smoke. This ritual was intended to drive off vampiristic spirits, thus sparing family members from whatever illness had claimed the deceased.

Extant sources reveal at least nine cases of corpse exhumation and burning in Rhode Island and Connecticut in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Probably the best known example was carried out by Captain Levi Young, who settled in Rhode Island after his discharge from the army.

Young became a successful farmer while his wife Anna bore him eight children in the space of 15 years. In the winter of 1827 Young’s eldest daughter Nancy became seriously ill with consumption. She deteriorated over several weeks and died in April, aged 19. Shortly after Nancy’s death other members of Young’s family, including his second child, Almira, developed similar symptoms.

On advice from elderly locals, Young exhumed Nancy’s body and burned it – while his surviving family members stood in the billowing smoke.

Source: Cumberland Town Council minutes, February 8th 1796. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.

1866: “The Thames porpoise has been shot, get back to work”

“It appears that for some time past this interesting visitor has been disporting itself in the ample bosom of Old Father Thames and has been much admired by the voyagers up and down the river.”

But the porpoise’s playful antics were not tolerated for long. On Wednesday October 3rd, two boats were launched from Blackfriars Road, each packed with men carrying rifles. They spent several hours firing shots into the murky Thames, in places where they thought the hapless cetacean might be swimming.

Eventually the shooters got lucky and the porpoise died after being hit with several shots. A heated argument later broke out between the riflemen over who was entitled to its carcass. Another newspaper expressed relief that the sideshow was at an end and everyone could get back to work:

“The creature of the deep having now been dispatched, the workers [of London] can now cease dallying along the Thames banks and attend to more rightful duties.”

Source: The Morning Post, October 5th 1866; Kentish Chronicle, October 8th 1866. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.

1827: Stephen King frightens himself to death

At the inquest, King’s doctor said that:

“…He was a man of good health and sober habits but was known to be superstitious, susceptible to visions and easily terrified.”

The attending physician suggested that King’s nervous disposition had contributed to his demise: the clap of thunder and King’s frightened response “caused the blood to flow too quickly to his head, producing apoplexy [stroke].” The coroner agreed but ultimately ruled that King had “died by the visitation of God”.

Sources: The Morning Chronicle, August 1st 1827; LMA coronial inquests, f.3, 1827. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.

1712: Edmund Harrold records his marital love-making

Harrold’s chronicle also lists brief but informative accounts of his sexual liaisons with his second wife, Sarah. According to Harrold they made love in both the “old fashion” – missionary position – but also in “new fashion”, though he does not elaborate on what this entailed.

In March 1712, Harrold wrote that “I did wife two times, couch and bed, in an hour and a half’s time”. On another occasion, he “did wife standing at the back of the shop tightly”. Another time they copulated on a bed on the roof, and still another time he mentions having sex “after a scolding bout”.

Not unsurprisingly, Sarah was frequently pregnant. In just under eight years of marriage she bore Harrold six children, though only two survived. The birth of her sixth child took its toll on Sarah’s health and she died in December 1712. According to Harrold’s diary his wife “died in my arms, on pillows… She went suddenly and was sensible until one-quarter of an hour before she died”. The newborn child, also named Sarah, also died four months later.

Harrold was distraught and resolved not to remarry, however, by March 1713 he admitted that his sexual urges were getting the better of him:

“It is every Christian’s duty to mortify their unruly passions and lusts to which ye are most prone. I’m now beginning to be uneasy with myself and begin to think of women again. I pray God, direct me to do wisely and send me a good one.”

Harrold did marry again. In June 1713 he wed Ann Horrocks, a customer who had called on him for a haircut – but she too was dead by early 1715. Harrold did not marry a fourth time and died in 1721, aged 43.

Source: Diary of Edmund Harrold, Wigmaker, 1712-15. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.

1884: Joe Quimby shoots his wife, gets a governor’s pardon

Quimby was duly charged with murder. In September, he appeared before a Mason County judge and was sentenced to 15 years’ hard labour. But in October 1891 Quimby, then less than halfway into his sentence, was given a governor’s pardon that generated considerable controversy at the time.

According to the papers of West Virginia governor Aretas B. Fleming, Quimby was pardoned on vague medical grounds because he “only hobbles about the place [the prison] doing nothing”. Quimby’s pardon was granted against the express wishes of the prison superintendent.

Source: Jamestown Weekly Alert, March 14th 1884; Public Papers of A. B. Fleming, October 23rd 1891. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.

1890: Hungarian woman prematurely buried, gives birth

According to the London Standard‘s retelling:

“A married woman named Gonda, belonging to a village near Szegedin, was reported to have died while under the hands of the midwife. The doctor granted a certificate of death and the woman was interred. Her husband, however, doubting whether she had really died, caused the body to be exhumed. On opening the coffin the woman was found lying on her side, with a newborn child dead beside her. An investigation into the case has been instituted.”

It may be that this was a case of ‘coffin birth’: the post-mortem expulsion of a foetus during decomposition. Wikipedia, of course, has a page on this phenomenon.

Source: Pester Lloyd, Budapest, September 12th 1890; The Standard, London, September 20th 1890. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.

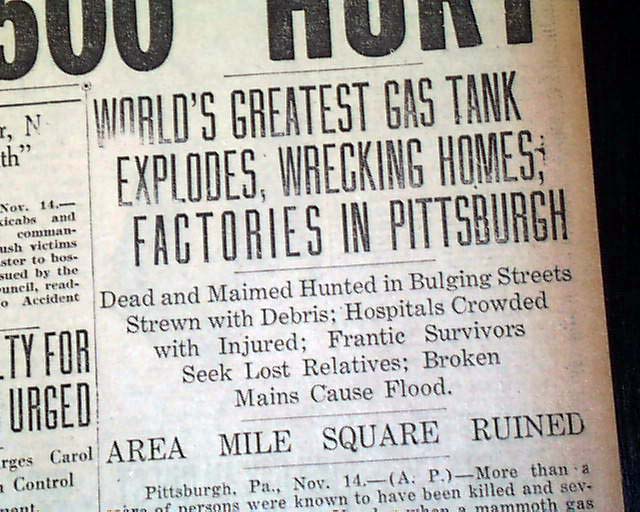

1927: Don’t fix leaking gas tanks with blowtorches

The Equitable Gas Company’s gasometer, a prominent city landmark, was billed as the largest man-made gas tank on Earth. On the morning of November 14th a team of workmen was sent to investigate a gas leak in an adjoining side tank. Thinking it safe, they began to repair the tank with acetylene blowtorches. Their flames ignited more than five million cubic feet of natural gas in the main tank, blowing it to pieces.

According to eyewitness accounts, the explosion created a fireball that reached 200 metres in height. The blast shook Pittsburgh like an earthquake and was felt in four different states. More than a square mile of the city was levelled, leaving several thousand people homeless. Metal shards, broken glass and burning debris rained down on the city for an hour. Large chunks of debris landed more than a mile from the scene.

More than 800 people were seriously injured but surprisingly, only 28 were killed, including the workmen who triggered the explosion.

Source: Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 15th 1927. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.

1724: Pirates employ musical bottom-stabbing

Pirates of the 17th and 18th century had a well justified reputation for brutality. They reserved their worst tortures for captured sea captains, particularly if evidence suggested they had mistreated their own crews. A 1669 report from a British colonial official described one form of pirate violence:

“It is a common thing among privateers… to cut a man in pieces, first some flesh, then a hand, an arm, a leg… sometimes tying a cord about his head and twisting it with a stick until the eyes shoot out, which is called ‘woolding’.”

Worse treatment was given to a woman in Porto Bello:

“A woman there was set bare upon a baking stone and roasted, because she did not confess of money which she had only in their conceit.”

In 1724, a mariner named Richard Hawkins, who spent several weeks captive aboard a pirate vessel, described a ritual dubbed the Sweat. It was usually employed to extract information from prisoners:

“Between decks they stick candles round the mizen mast and about 25 men surround it with points of swords, penknives, compasses, forks, etc., in each of their hands. The culprit enters the circle [and] the violin plays a merry jig… and he must run for about ten minutes, while each man runs his instrument into [the culprit’s] posteriors.”

Sources: Letter from John Style to the Secretary of State, 1669; Richard Hawkins in British Journal, August 8th 1724. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.

1662: A recipe for preserving severed heads

In his autobiography, published the year after his death, Ellwood recalled his experiences in Newgate, where he mingled with the scum of London: pickpockets, thugs and petty criminals. He remembered prostitutes being let into the prison on a regular basis:

“I have sometimes been in the hall in an evening and have seen the whores let in unto them… Nasty sluts indeed they were… And as I have passed them I heard the rogues and they [the women] making their bargains, which and which of them should company together that night.”

Ellwood also recalled his disgust at discovering the quartered bodies of three executed men stashed in a closet near his cell. He also witnessed their heads being treated by the executioner, so they could be put on display on a spike somewhere in London:

“I saw the heads when they were brought up to be boiled. The hangman fetched them in a dirty dust basket… he [and other prisoners] made sport with them. They took them by the hair, flouting, jeering and laughing at them, giving them some ill names [and] boxed them on the ears and the cheeks. When done, the hangman put them into his kettle and parboiled them with bay salt and cumin seed, [the first] to keep them from putrefaction, [the second] to keep the fowls from seizing on them.”

Source: The History of the Life of Thomas Ellwood, by the Same, pub. 1715. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.