According to Mangor, the farmer had gone through three young wives in the space of a few years. Each wife had been in good health but died within a day or two of contracting similar symptoms. The farmer’s own behaviour also aroused local suspicions. Six weeks after the death of his first wife he married a servant girl – but she lasted but a few years before falling victim to the mystery ailment, allowing the farmer to marry yet another maidservant.

Eventually, in 1786, wife number three died from the same malady:

“About three in the afternoon, while enjoying good health, she was suddenly seized with shivering and heat in the vagina… Means were resorted to for saving her life but in vain: she was attacked with acute pain in the stomach and incessant vomiting, then became delirious, and died in 21 hours.”

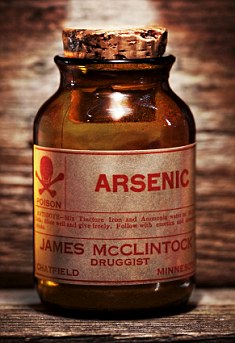

“Grains of arsenic were found in the vagina, although frequent lotions had been used in the treatment. The labia were swollen and red, the vagina gaping and flaccid, the os uteri gangrenous, the duodenum inflamed, the stomach natural.”

The farmer was arrested and placed on trial. To prepare for his testimony Dr Mangor conducted a number of experiments on cows. “The results clearly showed that when applied to the vagina of these animals”, he wrote, “it produces violent local inflammation and fatal constitutional derangement”.

The farmer, as might be expected, was found guilty. His punishment is unrecorded but it seems likely he was executed. The number of cows to die in the name of vaginal-arsenic justice is also not recorded.

Source: Dr C. Mangor, “The history of a woman poisoned by a singular method” in Transactions of the Royal Society of Copenhagen, v.3, 1787; Sir Robert Christison, A Treatise on Poisons &c., London, 1832. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.