The 1911 Revolution was the spontaneous but popular uprising that ended the long reign of the Qing dynasty. It is also known as the Xinhai Revolution, after the Chinese calendar year in which it occurred. The 1911 Revolution had apparently benign origins, beginning with disputes and protests over railway ownership in Sichuan province and surrounding areas. The flashpoint for revolution came in October when a republican-minded army unit mutinied in Wuchang, Hubei province. Their rebellious spirit spread to surrounding regions, igniting a tinderbox of revolutionary sentiment. By the end of 1911, nationalist revolutionaries were assembling to form a new government. These men, led by Sun Yixian, were determined to create a Chinese republic – but they lacked the means to force the Qing to surrender power. In the end, Sun Yixian reached a compromise with powerful military leader Yuan Shikai, whose intervention forced the abdication of infant emperor Puyi. This deal, however, placed power in the hands of Shikai, who was more interested in his own ambitions than furthering Chinese republicanism.

The collapse of the Qing dynasty came a decade after the failed Boxer Rebellion. In September 1901 the Qing government, represented by foreign minister Li Hongzhang, ratified the Boxer Protocol. For its role in supporting the Boxer movement and failing to protect foreigners in China, foreign powers hit the Qing state with punitive measures and costly reparations. The Boxer Protocol humiliated and greatly weakened the Qing regime, however, the Qing maintained their tenuous grip on power. In early 1902 Dowager Empress Cixi and her nephew, the politically impotent Guangxu Emperor, were permitted to return to Beijing. But the once fiercely conservative Dragon Lady was now a more compliant figure, ready to accommodate change if it meant prolonging her dynasty.

In her final years, Cixi authorised a raft of political and social reforms, some just as radical as reforms she had quashed in 1898. In 1905 Cixi approved a commission for the study of foreign political systems, a precursor to constitutional reform in China. The Qing bureaucracy was overhauled and new departments were set up to oversee the police, commerce, communications, foreign affairs, education and law. The imperial examination system was abandoned and steps were taken toward establishing a modern school system. There were economic reforms aimed at encouraging capitalist ventures. A more Westernised criminal code was adopted. Prohibitions on Manchu-Han marriage were lifted. Social evils like slavery, foot-binding and opium smoking were all banned. As radical as these late Qing reforms appeared to be, they were too insincere, too poorly implemented and came much too late to save the ailing dynasty. On November 15th 1908 Dowager Empress Cixi died in her sleep, a fortnight short of her 73rd birthday. Her demise came a day after the death of the 37-year-old Guangxu Emperor, who was almost certainly poisoned with arsenic, probably on Cixi’s orders. The Qing dynasty effectively died with Guangxu and his overbearing aunt. The imperial throne passed to the infant Puyi, leaving China in the hands of a two-year-old boy and his politically inexperienced father, at a time when it needed strong and decisive leadership.

Meanwhile, the dying dynasty faced two gathering storms: provincialism within and republicanism abroad. As Beijing’s power weakened, regional leaders expanded their own, some exploiting the Qing’s own reforms. Political power in China became even more decentralised. Outside China, Qing authority was challenged by Chinese studying abroad and nationalists living in exile. In 1904 Sun Yixian, then living in Hawaii, called on his countrymen to “expel the Manchu barbarians, revive China, establish a republic and distribute land equally among the people”. Sun and his followers organised political clubs like the Revive China Society and the Tongmenghui, with the aim of developing ideas for a post-Qing China. By the middle of the decade, these groups were revolutionary as well as republican. Now based in Malaya, Sun Yixian and his followers began organising uprisings in China. The year 1907 saw at least six unsuccessful uprisings against Qing rule: in Huanggang (May), Huizhou (June), Anqing (July), Qinzhou (September) and Zhennanguan (December). Their attempts to incite an anti-Qing revolution failed, mainly due to a lack of support from ordinary Chinese.

“The Qing government was overthrown not by a single rebellion but by a decentralised movement that devolved power to the provinces. However it proved extremely difficult to replace it with a government that was acceptable to all the provinces and regional economic and political interests that had been involved in the struggle to bring down the Manchus. Support for a constitutional monarchy had ebbed away and there was broad agreement among political activists that China needed a republican government – but there was no common understanding of what that would involve in practice, how it should be implemented and, of more immediate importance, who should be in power.”

Michael Dillon, historian

When the anti-Qing revolution came it began spontaneously, rather than at the command of Sun Yixian. The catalyst was a Qing decision to nationalise two privately-owned railways in central China, a policy designed to fund the government’s Boxer Protocol reparations. When announced in May 1911 this policy created a firestorm of protest, particularly in Sichuan province, where a number of local businessmen had invested their own money in the railway. Facing considerable losses if the government seized the railways, these investors created the Railway Protection Movement. This small but busy group organised strikes and protests in Chengdu, the Sichuan capital. In early September the Qing governor in Sichuan trie to short circuit the protest by sending in troops and arresting dissident leaders. This only worsened the situation and brought about the deaths of least 40 protestors. Beijing eventually backed down, replacing the governor and offering to better compensate those affected by the takeover of privately owned railways – but the situation in Sichuan had become dangerously inflamed.

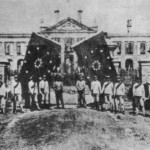

The Qing government, fearing further unrest, began to mobilise New Army regiments in neighbouring Hubei province. But these military units were themselves compromised by republicans and their sympathisers. A significant number of military personnel in Hubei, both officers and soldiers, had become members of secretive literary societies, meeting to read and discuss subversive political literature. By September 1911 these literary societies claimed more than 2,000 members. They had also connected with radical student and workers’ groups in Wuchang and other Hubei towns. This revolutionary coalition had been planning an uprising against the Qing and had been stockpiling weapons and munitions since early 1911. Their hand was forced by the accidental explosion of a bomb on October 9th. The bomb detonated in a Hankou building being used by dissident soldiers, leading to an investigation and exposure of their subversive activities. Facing arrest, the Wuchang regiment mutinied the following day (October 10th or ‘Double-Ten Day’). The rebel soldiers stormed government buildings, arrested loyalist soldiers and seized control of the city. On October 11th the rebels declared a republican government in Hubei province. There they hoisted a flag containing 18 connected stars, representing the unification of China’s 18 provinces.

The successful uprising in Wuchang kickstarted a wave of similar rebellions around China. Over the next six weeks, there were at least 22 different uprisings from Changsha to Jiangsu, from Shanghai to Shandong. In every location, rebels wrestled control from provincial politicians or bureaucrats and proclaimed their independence from the Qing. It was achieved with minimal violence for the most part, though some areas saw heavy fighting and considerable bloodshed. In Xi’an, Shaanxi province, the city’s Manchu population was protected for a time by loyalist Hui Muslims. When the defences fell in late October, around 10,000 Manchus were captured and indiscriminately slaughtered. Government forces also hit back against the rebels, recapturing several cities, including Wuchang itself. November saw the return of Sun Yixian, the nationalist writer and founder of the Tongmenghui, who had spent the last 15 years of his life calling for an end to Qing rule. Many considered Sun the only man capable of managing the difficult transition from monarchy to Chinese republic.

For all its optimism the new government, based in Nanjing, still had to find a way to rid China of the ailing Qing dynasty. Without a military force, it had no means to achieve this. One man who did was Yuan Shikai, who quickly became the figure on whom China’s future hinged. The Qing had attempted to secure Shikai’s loyalty on November 1st by appointing him as prime minister. Shikai, however, was more motivated by what he could acquire for himself than what he could do for his country. By December the new Qing prime minister was negotiating with republican agents about the creation of a new government – with Shikai himself as president. Meanwhile, on December 29th, the first assembly of the provisional republican government in Nanjing elected Sun Yixian as its president. China now had a choice of two republican presidents: one a well-credentialed nationalist who had dedicated his life to political modernisation, the other a self-serving military officer whose only credentials were his control of the army. The struggle between Sun Yixian and Yuan Shikai would shape the first years of the new Chinese republic.

1. The 1911 Revolution was a spontaneous nationwide rebellion that erupted across China in late 1911 and led to the abdication of the Qing dynasty.

2. The catalyst for the 1911 Revolution was the Railway Protection Movement that emerged in Sichuan in mid-1911, followed by the mobilisation of New Army units in Hubei.

3. The accidental detonation of a bomb in Wuchang threatened the exposure of hundreds of republican soldiers. Pre-empting their arrest, the soldiers mutinied, took control of Wuchang and formed a rebel government.

4. Dissatisfaction with the Qing and the success of the Wuchang uprising inspired rebellions in a multitude of cities and regions around China. By the end of 1911, the nation was in chaos.

5. Republicans led by the newly returned Sun Yixian formed a nationalist government in Nanjing- but they had to broker a deal to obtain the military backing of General Yuan Shikai.

© Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Glenn Kucha and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

G. Kucha & J. Llewellyn, “The Xinhai or 1911 Revolution”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/xinhai-1911-revolution/.

This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.