The Boxer Rebellion was an uprising against foreigners and Christians that erupted in eastern China in the late 1890s. The driving force behind this uprising was a secret society called the Fists of Righteous Harmony, dubbed the Boxers by the Western press. This movement was secretive, couched in Chinese mysticism and entirely closed to foreigners. Members of the Righteous Harmony movement were anti-foreign, anti-Christian and often critical of the Qing regime for its inability to resist foreign imperialism. They sought their own retribution against foreign imperialists in China, promising to “drive out the foreign devils”. Their members learned and practised a form of kung fu (the origin of the ‘Boxers’ name). Some attempted to perfect a mystical skill called ‘iron shirt’. This involved toughening and tensing the body to withstand blows. The best advocates of ‘iron shirt’, it was claimed, would be impervious to bullets.

The Boxer uprising began to take shape in the late 1890s, shortly after Germany seized control of Shandong province. German activity in Shandong led to heightened tensions between foreigners and peasants there. A coastal province to the south-east of Beijing, Shandong was known for its economic deprivation and poverty, caused to a large degree by its extreme variations in climate. Shandong’s terrain is mostly flat and arable but its farmland could be flooded by pouring rains in one year, then cracked and blistered by searing drought the next. Peasants in Shandong did not have an irrigation network to protect them from drought. They were unable to store much grain or food but lived hand-to-mouth from season to season. These factors contributed to three devastating famines in Shandong, between the mid-1870s and the end of the 19th century. Despite their suffering, the peasants in Shandong were known for their strong provincial loyalty, their resilience and their skill as soldiers. The Chinese military recruited actively in Shandong for this very reason.

In November 1897 a gang of armed men burst into a Catholic mission in Juye and murdered two German priests. On the advice of a Catholic bishop, Johann von Anzer, the German government sent two gunboats to the Shandong coast. German agents then bullied the Qing government into approving a German sphere of influence in the province. German Catholics were compensated with 3,000 taels of silver and allowed to fortify buildings to protect themselves from violent mobs. The Germans also forced the removal of local officials they believed were responsible for whipping up anti-foreign and anti-Christian sentiment in Shandong. A steady flow of German missionaries moved into Shandong, leading to disputes over land and religious sites. In Liyuantun, the site of a former Buddhist temple was seized by Christians for the erection of a church, leading to protests and some violence.

Violence against foreigners spread throughout Shandong in late 1898 and 1899. The suppression of the Hundred Days’ Reforms by Dowager Empress Cixi may have given some encouragement to the rising Boxer movement, which had attributed China’s weakness to the Guangxu Emperor. In October 1899 as many as 1,500 Boxers massed at a Buddhist temple in Pingyuan, north-west Shandong, and did battle with a much smaller contingent of government soldiers. The Battle of Senluo Temple, as it became known, shattered the myth that the Boxers had magical defences against bullets, nevertheless the Boxer movement continued to grow in Shandong and on the fringes of neighbouring provinces. By the end of 1899 gangs of Boxers were stalking around western Shandong, attacking foreigners and Chinese Christians. Buildings constructed, owned or used by foreigners were burned or torn down. Some Chinese were even assaulted or murdered for owning or carrying a Bible, English-language books or items obtained from Europeans. The Boxers also busily distributed anti-foreign propaganda in the form of art, posters, poetry, song and rumour.

“For the past 30 years [the foreigners] have taken advantage of our country’s benevolence and generosity, as well as our whole-hearted conciliation to give free rein to their unscrupulous ambitions. They have oppressed our state, encroached upon our territory, trampled upon our people and exacted our wealth. Every concession made by the Court has caused them, day by day, to rely more upon violence until they shrink from nothing. In small matters they oppress peaceful people; in large matters, they insult what is divine and holy. All the people of our country are so full of anger and grievances that every one of us desires to take vengeance.”

Dowager Empress Cixi, 1900

The relationship between the Boxer movement and the Qing government was uncertain. At first, the Boxers and the Qing leadership were antipathetic to each other. The Boxers considered the Qing corrupt and too weak to resist foreign incursions. Indeed, the Qing themselves were foreigners, Manchu rather than Han Chinese. Inside the government, Qing ministers condemned the Righteous Harmony movement. Li Hongzhang, China’s de facto foreign minister and the loudest supporter of Self-Strengthening, said that “under any enlightened sovereign these Boxers, with their ridiculous claims to supernatural powers, would have been condemned to death long ago”. In late 1899 the Qing appointed one of China’s best generals, Yuan Shikai, as governor of Shandong and he began suppressing Boxer unrest in the west of the province. But attitudes began to shift, as both the Boxers and Qing began to recognise the advantages each might provide to the other. Hoping the Boxers might drive foreigners from China, Cixi gave them her cautious support. Imperial edicts in January and April 1900 legalised the formation of civilian militias, providing a green light to Boxer recruiting. The Qing also filtered money to Boxer leaders, to support training of new members. The Boxers reciprocated by using the catchphrase “Revive the Qing! Destroy the foreigner!”

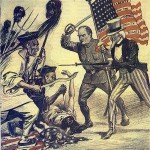

By the spring of 1900, thousands of Boxer rebels were traversing north-eastern China and drawing closer to Beijing. A mood of panic swept through foreigners in the capital, who fired off reports to their home governments, while the gunboats of foreign navies lingered menacingly off the Shandong coast. In June more than 20,000 Boxers flooded into Beijing and headed towards the capital’s diplomatic quarter, located around the Forbidden City. Foreign diplomats and officials from nine different countries, along with a small garrison of about 400 troops, heard of the Boxer advance and gathered inside the safety of a fortified compound. The German legation, located across town, was not so lucky. The German ambassador, Clemens von Ketteler, was killed in a street fight with pro-Boxer soldiers. Meanwhile, the foreigners within the compound, low on food and armed only with rifles and one single cannon, were besieged for almost two months (later made famous in the film 55 Days at Peking). Just as their supplies were almost exhausted, the foreign legations were rescued by troops from the so-called Eight Nation Alliance (Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Russia, Japan and the United States). This international force of around 20,000 soldiers entered Beijing on August 14th 1900, relieved the legations and drove the Boxers from the city. The Dowager Empress Cixi and the Guangxu Emperor both fled Beijing in handcarts and headed for the mountainous safety of Shaanxi province.

The Eight Nation expedition occupied the Chinese capital for weeks, dividing it up into areas of control. Foreign diplomats and troops were ordered to comb through Beijing, identifying and arresting suspected Boxers or Boxer sympathisers – but most just engaged in a campaign of indiscriminate looting, violence and rape. There were reports of diplomats sending home cartloads of valuables pilfered from Manchu homes. The Forbidden City was raided at least twice and stripped of priceless artefacts; there were numerous accounts of beatings, rape and street executions. The worst offenders seemed to be German soldiers, who were driven by a July 1900 speech given by their monarch, Kaiser Wilhelm II:

“Should you encounter the enemy, he will be defeated. No quarter shall be given. Prisoners will not be taken. Whoever falls into your hands is forfeited. Just as a thousand years ago the Huns made a name for themselves under Attila… may the name German be stamped by you in such a way that no Chinese will ever again dare to look cross-eyed at a German.”

In September 1901 the Qing government, represented by Li Hongzhang, was forced to sign the Boxer Protocol. The Protocol was, in effect, a costly peace treaty to atone for Boxer uprising. China agreed to pay reparations – one silver tael for each head of population (the equivalent of almost $US340 million). Anti-foreign groups were banned, military restrictions were imposed and foreign troops were permanently garrisoned in Beijing. Ten Qing government officials believed to have supported or encouraged the Boxers were executed. The Qing government was forced to issue a formal apology for the murder of the German ambassador and to erect a commemorative arch at the site of his death. Dowager Empress Cixi negotiated her return to Beijing and to government – but she did so without her old fire, agreeing to Western demands and later approving a program of social and political reforms. The once fearsome ‘Dragon Lady’ spent the last years of her rule a more compliant figure, called on by Western women for tea and photographs, while the Qing regime was just a shadow of a national government.

1. The Boxer Rebellion was a violent movement against foreigners and Christians that erupted in the eastern province of Shandong in the late 1890s.

2. Shandong was an impoverished province that was prone to famine. Germans used gunboat diplomacy to form a sphere of influence there in 1897, leading to heightened tensions.

3. The Boxers were locals who rallied against the “foreign devils”, using propaganda, martial arts, violence against foreigners and Christians and attacks on their property.

4. The Boxer movement expanded and invaded Beijing in June 1900. The Boxers and pro-Boxer soldiers murdered a German diplomat and laid siege to foreign legations.

5. Cixi and her government gave measured support to the Boxer movement, which was defeated by the Eight Nation Alliance in August 1900. A humiliating treaty, the Boxer Protocol, was later forced on China.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Glen Kucha and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

G. Kucha & J. Llewellyn, “The Boxer Rebellion“, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/boxer-rebellion/.

This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.