What is history? History is the study of the past, particularly people and events of the past. It is a pursuit common to all human societies and cultures. Human beings have always been interested in understanding and interpreting the past, for many reasons. While there is broad agreement on what history actually is, there is much less agreement on how it should be constructed and what it should focus on.

Stories, identities and context

History can take the form of a tremendous story, a rolling narrative filled with great personalities and tales of turmoil and triumph. Each generation adds its own chapters to history while reinterpreting and finding new things in those chapters already written.

History provides us with a sense of identity. By understanding where we have come from, we can better understand who we are. History provides a sense of context for our lives and our existence. It helps us understand the way things are and how we might approach the future.

History teaches us what it means to be human, highlighting the great achievements and disastrous errors of the human race. History also teaches us through example, offering hints about how we can better organise and manage our societies for the benefit of all.

History versus ‘the past’

Those new to studying history often think history and the past are the same thing. This is not the case. The past refers to an earlier time, the people and societies who inhabited it and the events that took place there. History describes our attempts to research, study and explain the past.

This is a subtle difference but an important one. What happened in the past is fixed in time and cannot be changed. In contrast, history changes regularly. The past is concrete and unchangeable but history is an ongoing conversation about the past and its meaning.

The word history and the English word story both originate from the Latin historia, meaning a narrative or account of past events. History is itself a collection of thousands of stories about the past, told by many different people.

Revision and historiography

Because there are so many of these stories, they are often variable, contradictory and conflicting. This means history is subject to constant revision and reinterpretation. Each generation looks at the past through its own eyes. It applies different standards, priorities and values and reaches different conclusions about the past.

The study of how history differs and has changed over time is called historiography.

Like historical narratives themselves, our understanding of what history is and the shape it should take is flexible and open to debate. For as long as people have studied history, historians have presented different ideas about how the past should be studied, constructed, written and interpreted.

As a consequence, historians may approach history in different ways, using different ideas and methods and focusing on or prioritising different aspects. The following paragraphs discuss several popular theories of history.

Great individuals

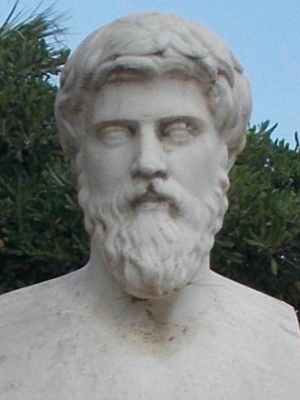

According to the ancient Greek writer Plutarch, history is primarily the study of great leaders and innovators. Prominent individuals shape the course of history through their personality, character, ambition, abilities, leadership or creativity – or conversely, their errors of judgement and failures.

Plutarch’s own histories were written almost as biographies or ‘life-and-times’ stories of these individuals. They explained how the actions of these great figures shaped the course of their nations or societies.

Plutarch’s approach served as a model for many later historians. It is sometimes referred to as ‘top-down’ history because of its focus on rulers or leaders.

One advantage of this approach is its accessibility and relative ease. Researching and writing about individuals is less difficult than investigating more complex factors, such as social movements or long-term changes. The Plutarchian focus on individuals can also more interesting and accessible to readers, who many prefer reading about people to abstract concepts.

The main problem with this approach is that it can sidestep, simplify or overlook historical factors and conditions that do not emanate from important individuals, such as economic changes, social conditions or popular unrest.

The winds of change

Other historians focus less on individuals and taken a more thematic approach, by looking at factors and forces that produce significant historical change. Some focus on what might broadly be described as the ‘winds of change’: powerful ideas, forces and movements that shape or affect how people live, work and think.

These great ideas and movements are often initiated or driven by influential people – but they become much larger forces for change. As these winds of change develop and grow, they shape or influence political, economic and social events and conditions.

One example of a notable ‘wind of change’ was Christianity, which shaped government, society and social customs in medieval Europe. Another was the European Enlightenment that undermined old ideas about politics, religion and the natural world. This triggered a long period of curiosity, education and innovation.

Marxism emerged in the late 19th century and grew to challenge the old order in Russia, China and elsewhere, shaping government and society in those nations. The Age of Exploration, the Industrial Revolution, decolonisation in the mid-1900s and the winding back of eastern European communism in the late-1900s are all tangible examples of the ‘winds of change’.

Challenges and responses

Some historians, such as British writer Arnold Toynbee (1889-1975), believed historical change is driven by challenges and responses. Civilisations are defined not just by their leadership or conditions but by how they respond to difficult problems or crises.

These challenges take many forms. They can be physical, environmental, economic or ideological. They can derive from internal pressures or external factors. They can come from their own people or from outsiders.

The survival and success of civilisations are determined by how they respond to these challenges. This itself often depends on its people and how creative, resourceful, adaptable and flexible they are.

Human history is filled with many tangible examples of challenge and response. Many nations have been confronted with powerful rivals, wars, natural disasters, economic slumps, new ideas, emerging political movements and internal dissent.

The process of colonisation, for example, involved major challenges, both for colonising settlers and native inhabitants. Economic changes, such as new technologies and increases or decreases in trade, have created challenges in the form of social changes or class tensions.

The study of dialectics

In philosophy, dialectics is a process where two or more parties with vastly different viewpoints reach a compromise and mutual agreement. The theory of dialectics was applied to history by German philosopher Georg Hegel (1770-1831).

Hegel suggested that most historical changes and outcomes were driven by dialectic interaction. According to Hegel, for every thesis (a proposition or idea) there exists an antithesis (a reaction or opposite idea). The thesis and antithesis encounter or struggle, from which emerges a synthesis (a new idea).

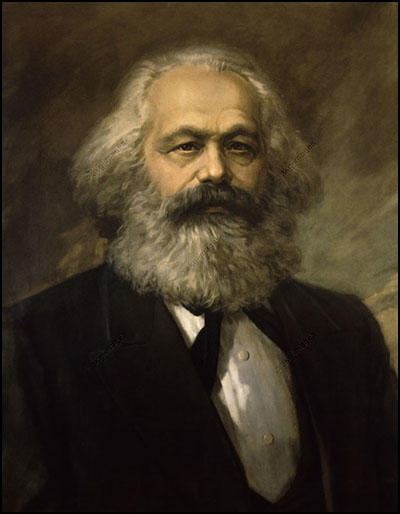

This ongoing process of struggle and development reveals new ideas and new truths to humanity. The German philosopher Karl Marx (1818-1883) was a student of Hegel and incorporated the Hegelian dialectic into his own theory of history – but with one important distinction.

According to Marx, history was shaped by the material dialectic: the struggle between economic classes. Marx believed the ownership of capital and wealth underpinned most social structures and interactions. All classes struggle and push to improve their economic conditions, Marx wrote, usually at the expense of other classes.

Marx’s material dialectic was reflected in his stinging criticisms of capitalism, a political and economic system where the capital-owning classes control production and exploit the worker, in order to maximise their profits.

The surprising and unexpected

Some historians believe history is shaped by the accidental and the surprising, the spontaneous and the unexpected.

While history and historical change usually follow patterns, they can also be unpredictable and chaotic. Despite our fascination with timelines and linear progression, history does not always follow a clear and expected path. The past is filled with unexpected incidents, surprises and accidental discoveries.

Some of these have unleashed historical forces and changes that could not be predicted, controlled or stopped. A few have come at pivotal times and served as the ignition or ‘flashpoint’ for changes of great significance. The discovery of gold, for example, has triggered gold rushes that shaped the future of entire nations.

In June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s car took a different route through Sarajevo and passed an aimless Gavrilo Princip, a confluence of events that led to World War I.

American historian Daniel Boorstin (1914-2004), an exponent of this fascination with historical accidents, once claimed that if Cleopatra’s nose had been shorter, diminishing her beauty, then the history of the world might have been radically different.

Citation information

Title: ‘What is history?’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/what-is-history/

Date published: September 23, 2020

Date updated: November 3, 2023

Date accessed: July 26, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.