To succeed in history, students should learn to think about history in new and challenging ways. Real history is more rigorous and challenging than simply ‘knowing what happened’ or memorising and reciting facts – it involves thinking about the past in different ways. This page explores some important skills and history concepts.

Thinking like a historian

In upper secondary and college levels, history students should begin to think and work like historians. They should learn to search for information and evidence, read extensively and examine relevant historical sources, like documents, images and artefacts.

More importantly, history students should pose difficult questions and think critically. They should be prepared to question the validity of evidence, challenge existing knowledge and evaluate the arguments of others.

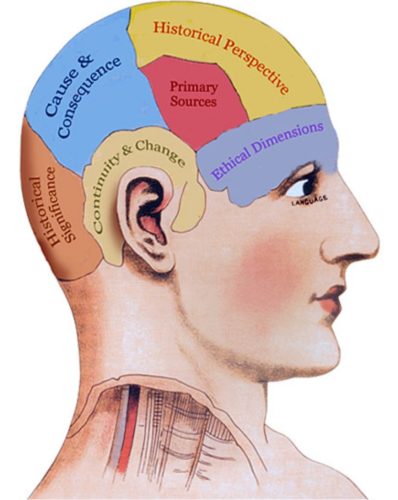

A first step towards thinking like a historian is learning important historical concepts. As with most disciplines, history has its own concepts, skills, terminology and approaches to thinking. Students will frequently encounter terms like change and continuity, cause and effect, sources and evidence. It is important for students to learn these concepts and, once confident, to incorporate them into their own research, thinking and writing.

Change

Change is perhaps the most important of all historical concepts. Exploring, explaining and evaluating change is a universal focus for people who study or work in history. When investigating the past, most historians focus not on a specific moment in time but on how society changed and evolved over a longer period.

Human societies are never static. All societies are undergoing some form of change, however minor or unnoticeable it might be. One of the aims of a historian is to identify, describe and explain this process of change. They seek to find out the conditions and factors that caused change. They try to identify how this change affected the society in question.

The speed of change is also significant. Most historical change is slow, gradual or evolutionary: it causes little disruption to society and its individual members. But some historical change – like the upheaval caused by a war, a revolution, an economic depression or political radicalism – can be abrupt, fast moving and tumultuous.

Continuity

Continuity is the opposite of change. It is where things stay more or less the same. Historians are interested in change but they are mindful that not everything changes. Even during a period of great upheaval, some institutions, traditions, ideas and human behaviours will remain constant.

For example, the rise of a new monarch or political leader might bring significant change but the political system itself may remain the same. A revolution might hope to create a new society but it may not change the ways people think or behave. Revolutionary leaders might rebel against oppressive governments, only to end up using similar methods themselves.

Examples of continuity can be found in every historical period of significant change. Good historians and history students are able to identify and recognise examples of continuity, even amid the most tumultuous change.

Cause and effect

Two important historical concepts are cause and effect. Every significant event, development or change is triggered by at least one cause. To understand an event, the first task of the historian is to identify and study the factors that caused it.

Sometimes historical causes can seem straightforward. When studying a significant historical event or development, it often seems obvious that ‘X’ appears to have brought about ‘Y’.

In reality, history is rarely so simple or apparent. Significant events usually have multiple causes, some of which may be interconnected, disguised or subtle. Historical causes also can evolve over the long term, building up over months, years, even decades and generations – or they can be short-term causes, triggering change in a month, a week or even a day. Causes can be political, like the passing of a new law or policy; or economic, like a new invention or the development of new forms of trade or commerce.

Every significant historical action or event also has effects or consequences. Historians study the aftermath of these actions and events, in order to identify and evaluate the impact they had on society. Understanding the effects of an event or change allows us to gauge its significance or importance.

Significance

Significance describes the relative importance or value of a topic or issue. Evaluating historical significance boils down to choosing which things are more important or notable than others.

Historical significance is a critical concept because it shapes what we study and the conclusions we reach. Those who design history courses, for example, will choose to focus on certain people, places and events because they consider them of greater significance than others. History teachers emphasise certain topics or pieces of evidence because of their perceived significance.

Likewise, historians form conclusions and arguments based on historical significance. They reach conclusions that certain people, events or factors had more impact or influence on the past than others.

Identifying historical significance can appear easy. It seems obvious that Adolf Hitler, for instance, had a much greater impact on the past than Wilhelm Cuno. But historical significance is often subjective (a matter of personal opinion) and contestable (open to challenge). Historians often disagree over historical significance, leading to an emphasis on different things and contrasting or conflicting interpretations.

History students are frequently asked to identify and discuss significance in coursework or assessment pieces. For example, “what was the significance of the Stamp Act?” or “who was the most significant figure in the Weimar Republic?” When evaluating significance in these contexts, there is not necessarily one correct answer. You must use your own judgement, form your own conclusions and support them using evidence.

Sources

Sources are materials from the past that can provide us with information about the past. They are sometimes referred to as primary sources, contemporary sources or artefacts.

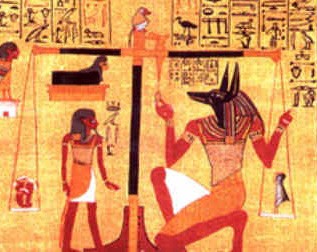

There are many different types of primary sources. Some of the more common ones include official documents and records, letters, chronicles, diaries, old newspaper articles, physical artefacts, paintings, photographs, murals, maps, buildings, furniture, clothing, militaria, archaeological relics and even corpses.

Historians use sources to access and acquire information about the past. This information, if useful and reliable, can be used as evidence when forming conclusions. Every historical source reveals something about the past, though some sources obviously reveal more than others. A source like the Bayeux Tapestry, for example, will furnish more evidence than a weapon found on the battlefield at Hastings. Examining historical sources and extracting evidence is a critical skill for historians and history students alike.

Evidence

Evidence refers to important historical knowledge extracted or derived from sources. This evidence is then used to support the conclusions formed by historians.

Historical research is chiefly concerned with locating, extracting and interpreting evidence. Significant documents, for example, might contain important evidence about a particular person or event. The examination of corpses might reveal evidence about mortality rates and causes of death. The examination of artefacts might reveal information about the people who created and used them, such as their technological and manufacturing skill and their standards of living.

Evidence is the cornerstone of historical understanding. Without evidence, even the best arguments or conclusions can be little more than guesswork. Evidence is as important to history students as it is to historians. Students must learn to extract evidence from sources and then use this evidence to support and justify their own conclusions.

Frameworks

When writing about or discussing the past, historians often use frameworks like political, economic, social and cultural. These frameworks serve as organisers or ‘dividers’, allowing them to discuss specific sections or groups within a much larger population.

Human society is not a single, amorphous mass: it has different people and groups who carry out different functions. Some people lead, make laws and decisions and exercise power. Some control production, goods and labour. Some influence the way people think or live. Others simply work and exist, sometimes in difficult conditions.

Frameworks like political, economic and social allow historians to write about a society with greater depth, precision and complexity, while avoiding generalisation. History students should get to know these frameworks (summarised below) and learn to incorporate them into their own thinking and writing.

Political

The term political refers to the institutions, people and processes responsible for leadership and decision-making in a society. Political decisions and actions can have a profound impact on the rest of society. For this reason, many historians often look first at political leaders and governments, to learn how they acted and responded to certain problems or challenges.

Political leaders include monarchs and emperors, presidents, governors, ministers, mayors, community leaders and government officials. The obvious political institution is government, which might exist at a number of levels (national, state, provincial, municipal or communal).

Other political institutions include parliaments, congresses, assemblies, committees, courts, political parties and the bureaucracy (government departments or public service). Political concepts include values, ideology, laws, policies or decrees.

Economic

The term economic refers to a society’s production and distribution of physical items. Every individual has needs (food, water, housing and clothing) and wants (such as consumer goods or luxury items). All societies develop their own systems of gathering, producing and sharing these wants and needs. Economics is the study of this activity.

Economic concepts include production, wealth, land, capital, money, markets and labour. Different sectors of economic production include industry, manufacturing, agriculture and mining. Other economic activities include financial practices like money, taxation, banking and government revenue and expenditure. Ownership of land, capital and the distribution of wealth are also important economic measures.

Economics is a complex study in its own right and difficult to master – but it is impossible to understand any society without at least a basic understanding of its economic processes and relationships.

Social

Broadly speaking, the social framework covers how societies are organised and how people live and behave. Many historians focus on social conditions and the ways that societies organise and sustain themselves.

Some social aspects can be studied and quantified with statistics on demographics, population density, urban populations, family size, birth and death rates and infant mortality. Historians also look at other social aspects and factors, including standards of living, health, gender roles and status, the size and role of families, the availability and level of education, literacy and communication, religious beliefs and social customs.

All societies have hierarchies or power structures, based on age, privilege, religious status, economic class or other factors. Historians may also evaluate social mobility (the ability of an individual to move up through the classes) and political participation (the relationship between ordinary people and those who govern or rule).

Cultural

The cultural framework has two different interpretations, both of interest to historians. To some, culture describes the unique ideas and customs of a society – in other words, the behaviours and habits that distinguish one nation or people from another. This may include things like language and communication, food, music, costumes, sports, religious rituals, ceremonies and celebrations, pastimes and leisure activities.

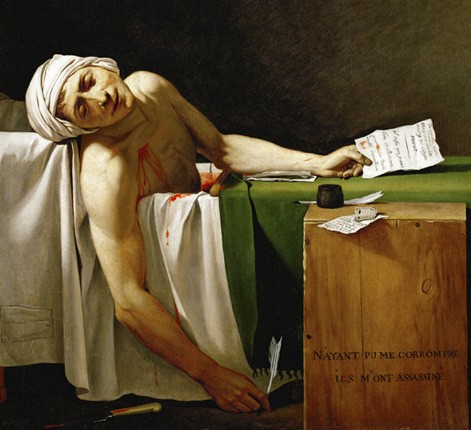

Another interpretation of culture is artistic and creative activities, through which people express their ideas, values and feelings. This includes pursuits like literature, poetry, music, painting and sculpture. Despite their creative basis, these works of art can express or reflect contemporary ideas, values and conditions.

For this reason, historians study artists, artistic movements and individual works of art, to evaluate how they were influenced by contemporary ideas, events and conditions. Some artists, such as the late 18th century Frenchman Jacques-Louis David (above) produced work with explicit political themes. This kind of artistic work can constitute important historical evidence.

Historiography

Historiography is the close study of history and how it evolves, reaches different conclusions and changes over time. It is largely concerned with the methods and approaches of historians: the men and women from whom we ‘receive’ history and historical understanding.

There is no single understanding or ‘truth’ in history; different historians often reach different conclusions about the same period, event or issue. History is also subject to change and reinvention. As new historians emerge, they apply new ideas, values and approaches that modify our understanding of the past.

The term historiography can also refer to the body of historical research and writing on a particular topic, such as the ‘historiography of Nazi Germany’ or the ‘historiography of Abraham Lincoln’.

Historiography is a complex and difficult area of history but one that most students will need to come to terms with. For more information on historiography, visit this link.

Citation information

Title: ‘History concepts’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/history-concepts/

Date published: September 30, 2021

Date updated: November 3, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.