Many believed the Troubles in Northern Ireland could be ended with political solutions. If Catholics and Nationalists were better represented in government, they argued, then support for the Provisional IRA would dwindle. A consociational or power-sharing government seemed the best hope. This would distribute executive power between Unionists and Nationalists, reducing discrimination, encouraging political partnership and boosting stability. There were three significant difficulties to overcome. The first was convincing everyone to accept power-sharing – a formidable task, given the extreme positions of some groups. The second difficulty was formulating a stable and functional system acceptable to all parties. The third was determining a role for the Republic of Ireland. These issues were resolved, in theory at least, by the Sunningdale Agreement. Signed in December 1973, this agreement established three political bodies: a proportionally-elected Northern Ireland Assembly; an executive government with power shared by Nationalists and Unionists; and a “Council of Ireland”, made up of delegates from both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Green paper, white paper

The origins of the Sunningdale Agreement can be traced back to October 1972, with the formulation of a green paper (discussion document) by Northern Ireland Secretary of State William Whitelaw. Titled “The Future of Northern Ireland“, Whitelaw’s paper outlined the problems facing the Six Counties and some suggested solutions. This was followed by a March 1973 white paper (policy paper) called “Northern Ireland Constitutional Proposals“. This paper provided several firmer proposals. A new Northern Ireland Assembly would be elected to replace the old Stormont parliament. Elections would use proportional representation, undermining Unionist gerrymanders and giving Nationalists a better voice in government. Once elected the Assembly would negotiate the formation of a power-sharing executive. The 1973 white paper also called for the formation of the “Council of Ireland”, a bilateral committee with representatives from Belfast and Dublin.

The white paper and its power-sharing provisions caused a split in Unionist ranks. Conservatives like Ian Paisley and his Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) were outraged that Irish politicians in Dublin and Nationalists in Ulster might be handed a seat in the government of Northern Ireland. Even the more moderate Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) was divided on power-sharing, its candidates declaring themselves either ‘pro-white paper’ or ‘anti-white paper’. On March 8th 1973 the British government held its controversial Border Poll, a referendum on whether Northern Ireland should remain in the United Kingdom or reunify with Ireland. Catholics boycotted this referendum, resulting in a 98 percent victory for “remain”. The British Parliament passed the Northern Ireland Assembly Bill in May 1973 and elections for the Assembly were held in late June. Unionists finished with a healthy majority, winning 50 of the Assembly’s 78 seats, while the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) won 19.

A coalition cabinet

“A new form of government was in the process of being born. While perhaps an ugly child, it was at least a live birth… Few people would have imagined a year earlier that Brian Faulkner – the man who had publicly opposed the concept of power-sharing – would be sitting down so soon with his enemies. The supporters of this devolved government hoped that finally a new dawn had broken and that the dark days of violence would be replaced by this power-sharing initiative.”

Feargal Cochrane, historian

With the Assembly in place, pro-white paper parties met in November 1973 to create a power-sharing executive. They settled on a coalition cabinet, containing members from the largest parties in the Assembly. UUP leader Brian Faulkner became Northern Ireland’s first Chief Executive and the straight-talking SDLP leader Gerry Fitt his Deputy Chief Executive. Five portfolios (education, finance, agriculture, environment and information) were handed to UUP members. Three portfolios were given to members of the SDLP, including commerce to John Hume, housing to Austin Currie and health and social services to Paddy Devlin. Oliver Napier from the liberal Alliance party filled the last remaining place in the Cabinet, becoming legal minister. The formation of this coalition executive was a remarkable development. Even during the election campaign, Faulkner himself told reporters he would never govern alongside anyone “whose primary objective was to break the link with Great Britain”. Yet here he was weeks later, sharing a cabinet with men from the Nationalist SDLP.

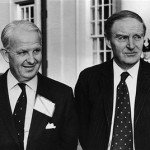

While moderate Unionists could tolerate a power-sharing cabinet, they could not stomach the proposed Council of Ireland. Always suspicious of Dublin, Unionists saw the Council as a significant step towards Irish reunification. Nationalists, in contrast, supported the idea. After weeks of unsuccessful negotiations on a bilateral council, the British government called a four-day schedule of meetings in Sunningdale, Berkshire. Held in early December 1973, these meetings were attended by British prime minister Edward Heath, Irish taoiseach Liam Cosgrave and representatives of the UUP, SDLP and Alliance parties. Dissenting Loyalist parties DUP and the Ulster Vanguard were not invited. The terms of the Sunningdale Agreement were thrashed out in these sessions, some of which went on late into the night. After heated debate, Unionist representatives ultimately conceded the formation of a Council of Ireland. The negotiating parties signed the final agreement on December 9th.

The Loyalist backlash

The Sunningdale Agreement set off alarm bells back in Northern Ireland, particularly in Loyalist circles. Many were outraged that Faulkner, the leading Unionist negotiator at Sunningdale, had agreed to the Council of Ireland but had failed to secure their demands (formal recognition of Northern Ireland by Dublin, a crackdown on IRA suspects in the Republic and new security measures). On January 4th 1974, four weeks after the agreement was signed, the Ulster Unionist Council voted 427 to 374 against the new Council of Ireland. This forced Faulkner’s resignation as head of the UUP, though he retained his position as Chief Executive. In the British general election in February 1974 Ulster Unionists won 11 seats in the House of Commons – but refused to support the Conservative Party, a protest against the Sunningdale Agreement. This effectively cost Heath and the Conservative Party government.

Opposition to the Sunningdale Agreement intensified when the Northern Ireland Assembly met on January 22nd 1974. Hardliners from the DUP and Ulster Vanguard turned the session into a farce. One DUP member reportedly tried to steal the mace, while a Vanguard deputy did a ‘war dance’ atop the tables and others hurled around chairs. Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) officers were called in to clear the assembly and some received minor injuries. Paisley was himself seen scuffling with police. The situation became untenable and by March even moderate UUP members had withdrawn their support for Sunningdale. The final blow came in May 1974 when the Ulster Workers’ Council (UWC), a Loyalist-dominated labour association, organised a general strike for May 15th. Loyalist paramilitaries threw their weight behind the strike, harassing and intimidating non-UWC members. Eventually, Northern Ireland’s heavy industries came to a grinding halt. With the economy at risk and Loyalists unwilling to compromise, Faulkner and his coalition executive resigned on May 27th. This marked the death of the Sunningdale Agreement and the first attempt at power-sharing, as Northern Ireland returned to Direct Rule under the British government.

1. The Sunningdale Agreement was the first attempt to implement a power-sharing government in Northern Ireland, to give Nationalists a fairer voice in government.

2. Sunningdale began with the British government publishing two papers that floated power-sharing and bilateral relations with Dublin as a possible way forward.

3. A new Northern Ireland Assembly was elected in June 1973. A power-sharing executive was then established, in the form of a UUP-SDLP-Alliance coalition cabinet.

4. The sticking point for Loyalists was the proposed Council of Ireland: a bilateral council involving politicians from both Belfast and Dublin.

5. When the Council of Ireland was formalised in the final Sunningdale Agreement, signed December 1973, Loyalists responded by splitting the UUP, disrupting the Assembly and organising a general strike. Sunningdale failed when the executive resigned in May 1973.

The Future of Northern Ireland green paper (October 1972)

Northern Ireland Constitutional Proposals white paper (March 1973)

The Sunningdale Agreement (December 1973)

Irish taoiseach Liam Cosgrave on the Sunningdale Agreement (March 1974)

© Alpha History 2017. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebekah Poole and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Poole and S. Thompson, “The Sunningdale Agreement”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/sunningdale-agreement/.