One notable action of the Provisional IRA’s ‘Long War’ was a series of protests and hunger strikes in British prisons. These protests were triggered by the British government’s removal of Special Category Status (SCS) for paramilitary prisoners in January 1976. Until then, these inmates had claimed the status of prisoners of war or political prisoners. Westminster’s decision to withdraw SCS meant that Republicans and Loyalists in Northern Ireland’s prisons were to be treated like common criminals. This infuriated both the prisoners and the leadership of paramilitary groups because it recast their actions as criminal rather than political or revolutionary. Republican protests were concentrated in HM Prison Maze’s H Block but mimicked by prisoners and internees elsewhere. The protestors employed different tactics and maintained their pressure for more than five years. Their efforts secured the restoration of Special Category privileges – but only after the deaths of ten Republican hunger strikers.

The 1972 hunger strike

The road to the prison protests begins in the early 1970s. In 1971 Billy McKee, commander of the Provisional IRA in Belfast, was arrested for firearms offences, convicted and jailed in Crumlin Road, a British prison in northern Belfast. McKee was outraged that he and other Republicans were treated as criminals rather than prisoners of war. In May 1972 McKee and several others launched a hunger strike, declaring their intention to refuse food until Republican prisoners were granted political status. Hunger strikes had been employed before as a political protest, both by Irish dissidents and British suffragettes, though they rarely succeeded. McKee, however, was determined. Ten days into the strike he began refusing fluids as well as food. News of McKee’s determined stand quickly reached the outside world. He was joined by other hunger strikers in Crumlin Road, in other prisons, even in some Nationalist towns. By mid-June 1972, McKee and two other strikers were in a perilous condition.

The situation outside the prisons was also evolving. Both the Provisional IRA and Official IRA had launched an intense campaign of violence in the wake of Bloody Sunday. The Official IRA had been severely embarrassed by its bombing of the British Army’s Aldershot base on February 22nd; this attack killed five female cleaners, an elderly gardener and a Catholic chaplain but no soldiers. On May 30th Official IRA leader Cathal Goulding agreed to a ceasefire, committing to use paramilitary violence only in a defensive capacity. With McKee and his fellow hunger strikers close to death, the situation apparently easing and Provisional IRA delegates also willing to negotiate, Britain’s Secretary of State for Northern Ireland William Whitelaw relented. On June 20th Whitelaw granted Special Category Status (SCS) to paramilitary volunteers held in British prisons.

Freedom fighters, not criminals

The approval of SCS meant prisoners convicted of scheduled offences were treated in a similar fashion to enemy combatants. They were free to associate with other Republican or Loyalist prisoners; they were not required to undertake prison-based work; they did not have to wear a prison uniform and they could receive additional food and tobacco parcels. Britain’s endorsement of SCS also had political implications because it acknowledged paramilitary volunteers as revolutionaries or freedom fighters rather than violent gangsters or thugs. Whitelaw had chosen the “Special Category” wording carefully, avoiding terms like “political status” or “prisoners of war”. Despite this, Republicans hailed the approval of SCS as a victory. By 1976 there were around 3,000 prisoners in Northern Ireland and around half this number were entitled to Special Category Status.

The situation changed in 1974 with the election of a Labour government (February) and the appointment of Merlyn Rees as Northern Ireland Secretary of State (March). Labour opted for a three-armed policy approach. Step one was to ease violence and disorder in Northern Ireland (“normalisation”). Step two would see British soldiers withdrawn and replaced by local forces (“Ulsterisation”). The final step was to depoliticise the situation, painting the Troubles as the work of thugs and gangsters (“criminalisation”). In November 1975 Rees announced his intention to phase out Special Category Status. Prisoners jailed for scheduled offences after March 1st 1976 would no longer be able to apply for SCS. This decision triggered several days of violence on both sides of the sectarian divide. The Provisional IRA condemned the withdrawal of SCS in strong terms: “We are prepared to die for the right to retain political status. Those who try to take it away must be fully prepared to pay the same price.” The Provos made good on this threat, gunning down a Catholic prison officer, Patrick Dillon, outside his home near Omagh.

The protests begin

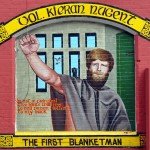

The first spark of protest came in September 1976, when 18-year-old Kieran Nugent was sentenced to the Maze for hijacking a van. Nugent was the first Provisional IRA volunteer to be jailed since the revocation of Special Category Status. Ordered to change into prison uniform, Nugent refused, telling guards they would have “to nail the clothes to my back”. Without other clothing, Nugent wrapped himself in a prison-issue blanket. Other inmates showed their solidarity by following suit. By the end of 1976 more than 300 Republican inmates were refusing to wear prison uniform, spending their day either stark naked or wrapped in a blanket. Their refusal to follow prison orders attracted further punishments, including loss of remission, cell furniture and exercise periods. Their campaign became known as the ‘Blanket Protest’.

This campaign evolved into the so-called ‘Dirty Protest’, which began in April 1978. Fearing attacks by prison officers, several Republican prisoners refused to leave their cells to use the shower or toilet facilities. A delegation requested the installation of showers in cells but this was denied. In retaliation, the prisoners refused to empty or clean out cell buckets provided for human waste, instead smearing urine and excrement across the walls of their cells. These protests were copied by prisoners elsewhere. In February 1980 Republican inmates at Armagh Women’s Prison smeared the walls of their cells with menstrual blood. Prison authorities responded by forcing prisoners out of their cells, hosing down the walls and spraying disinfectant. Inmates simply repeated the protest once back in their cells.

Unlike the Blanket Protest, which had passed with little attention, the Dirty Protest attracted coverage in the media. By late 1978 the actions of the ‘Blanketmen’ were being discussed in the worldwide press. This was in some part due to Tomás Ó Fiaich, the Catholic archbishop of Armagh and later Cardinal of Ireland, who visited the Maze protestors during the summer of 1976. In August the archbishop issued a public statement condemning the treatment of the H Block prisoners and the conditions they were forced to endure. Ó Fiaich also praised the prisoners’ political resolve:

“It is evident that they intend to continue their protest indefinitely and it seems they prefer to face death rather than to submit to being classed as criminals. Anyone with the least knowledge of Irish history knows how deeply this attitude is in our country’s past.”

Thatcher and the hunger strikes

The situation intensified after the election of Margaret Thatcher and the Conservatives in May 1979. Thatcher was determined not to bow to the demands of paramilitary groups or their members. She refused to consider the restoration of Special Category Status and used the media to reinforce her position. “A crime is a crime is a crime”, she told one press conference in Dublin. “Murder is a crime. Carrying explosives is a crime. Maiming is a crime. Murder is murder is murder. It is not now, and can never be a political crime. So there is no question of political status.” Republican inmates in Maze Prison responded by commencing a hunger strike on October 27th 1980. There were seven participants at first, a number chosen to match the rebel signatories of Easter 1916. They were later joined by others in the Maze and three female prisoners at Armagh. With at least two prisoners on the brink of death, the hunger strike was called off shortly before Christmas 1980.

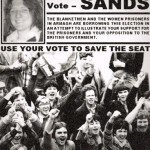

Believing the British were on the brink of conceding, IRA inmates organised a second hunger strike in March 1981. The instigator this time was Bobby Sands, a 27-year-old from County Antrim. Sands was thoughtful, intelligent and literate, a noted writer of Republican essays and songs. During the late 1980 hunger strike, he became commander of Provisional IRA inmates in the Maze. Sands began his hunger strike on March 1st, refusing food until SCS privileges were restored. He was joined by other prisoners at staggered intervals, a strategy designed to lengthen the hunger strike and attract media attention. The situation took an unusual turn in April with the unexpected death of Frank Maguire, the Nationalist MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone. After some consideration, Republican groups nominated Bobby Sands as a candidate in the April 9th by-election. Again, this was designed to attract media coverage.

Bobby Sands MP

Despite remaining behind bars during the campaign, Sands won the seat of Fermanagh and South Tyrone by a narrow margin (553 votes). In doing so he became Westminster’s youngest Member of Parliament. Unionists were outraged by Sands’ election, condemning Nationalist parties like the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) for stepping aside to hand a parliamentary seat to a convicted terrorist. Sands’ example was followed by other Republican prisoners who stood for election. This led to Westminster passing the Representation of the People Act (February 1983) which, among other reforms, prevented prison inmates from voting or standing in an election. None of this mattered to Sands, however, who died on May 5th after 66 days without food. He was the first of ten Irish Republican prisoners to die during the hunger strike. Seven of the dead were IRA volunteers while three belonged to the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA). All were aged between 24 and 30. The hunger strike was formally ended in early October when families of the participants authorised medical intervention if the strikers lapsed into unconsciousness.

Media coverage and responses to the 1981 hunger strike were intense. The British press hailed Thatcher for refusing to concede to terrorists, even those prepared to starve themselves to death. In point of fact, British authorities gradually restored most SCS privileges in late 1981. The Provisional IRA condemned Thatcher’s cold-blooded determination to watch men die over a point of principle. The international press criticised Thatcher and her government for their handling of the hunger strike. Bobby Sands’ death received significant attention worldwide and his funeral was attended by around 100,000 people. Like Bloody Sunday, Sands’ death triggered a surge in the level of violence and an increase in Provisional IRA enlistments. After a period of relative calm, the Provos returned to targeting security forces in Northern Ireland, killing 26 soldiers and policemen in a seven month period. Thatcher’s handling of the hunger strike also motivated the Provisional IRA’s attempt to assassinate her in Brighton in October 1984.

1. The prison protests and hunger strikes of the 1970s and early 1980s were motivated by the British government’s 1976 withdrawal of Special Category Status (SCS).

2. SCS was granted to Republican and Loyalist prisoners jailed for scheduled offences. It entitled them to be treated as political prisoners with additional privileges.

3. The Labour government withdrew SCS as part of its policy of “criminalisation”. Republican prisoners objected to having their struggle de-politicised and depicted as common crime.

4. The first major protests against this were the Blanket Protest (with prisoners refusing to wear uniforms) and the Dirty Protest (where prisoners smeared excrement on cell walls).

5. In 1980-81 Irish Republican prisoners staged hunger strikes, refusing to eat until SCS had been restored. These strikes culminated in the deaths of ten prisoners, including elected MP Bobby Sands. This received worldwide attention and caused a resurgence in violence and IRA recruiting.

Merlyn Rees withdraws Special Category Status for prisoners (November 1975)

The Provisional IRA responds to the withdrawal of SCS (March 1976)

Merlyn Rees condemns violence triggered by SCS (March 1976)

Archbishop Ó Fiaich on the conditions in Maze’s H-Block (August 1978)

Bobby Sands recalls a forced body search in HM Prison Maze (1981)

© Alpha History 2017. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebekah Poole and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Poole and S. Thompson, “H Block and hunger strikes”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/h-block-hunger-strikes/