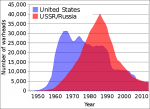

The United States and Russia, the Cold War’s two main protagonists, have had a turbulent relationship since 1991. The US remains the world’s largest superpower, both economically and militarily. Despite the global financial crisis of 2008 and other problems, the American economy remains the largest and wealthiest in the world. The US government is still the world’s preponderant military power, with around 1.2 million full-time military personnel and 800,000 reservists. Washington spends more than $US600 billion per year on defence, almost three times that of China, nine times that of Russia and more than the next eight nations combined. The US remains the most influential member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) which since 1991 has continued to operate and expand, despite the end of the Cold War. Russia, in contrast, has been significantly weakened by the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It remains an important regional power with a nuclear arsenal and powerful military but has surrendered its global superpower status to the US and China.

From Soviet Union to Commonwealth of Independent States

The Cold War was ended by the dissolution of the Soviet Union on Christmas Day 1991. The USSR was replaced by a new entity called the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). It was formed to collaborate and coordinate policies on issues such as free trade, finance, security, immigration and crime prevention. Unlike the Soviet Union, the CIS is a loose confederation with no formal power over its member-nations. The CIS had 11 founding member-nations, all of which were former Soviet republics (Russia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan). Georgia joined the CIS in 1993 but has since withdrawn, along with Armenia and Ukraine. Russia remains the most powerful member-nation of the CIS – and in many respects its de facto leader. Despite the organisation’s lack of coercive power, Moscow has often been accused of determining CIS policy unilaterally or exerting undue pressure on other member-nations of the CIS.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, coupled with heavyhanded Russian policies during the 1990s, gave rise to nationalist and independence movements within the former USSR. The most violent of these separatist groups was formed in Chechnya, a small region in the North Caucasus, in 1991. Chechen separatists spent the next decade battling Moscow for independence. Their struggle included two full-scale wars (1994-96 and 1999-2000) that claimed more than 100,000 lives, including around 10,000 Russian soldiers. Chechen separatist violence continued into the 21st century and included acts of terrorism such as the Beslan school siege (September 2004) which claimed the lives of 186 children. Russian forces eventually gained control of Chechnya, eradicated separatist and terrorist groups and imposed a pro-Moscow regime. Russia has also had difficult relations with Ukraine, whose politicians and people have been divided on whether to retain ties with Moscow or forge new links with the West, such as seeking membership of NATO and the European Union (EU). In 2014 Russian troops annexed the Crimean peninsula, an autonomous province of Ukraine, and installed a pro-Russian government there. Internecine fighting erupted in eastern Ukraine and continues today, with the clandestine involvement of Russian forces. In July 2014 a Russian-operated missile team operating in eastern Ukraine shot down a civilian airliner, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, killing 298 people.

The honeymoon period

Diplomatic relations between the US and Russia improved through the 1990s. Both nations signed an arms control treaty in January 1993, trade links were increased and Russian president Boris Yeltsin began a cordial relationship with his American counterpart Bill Clinton. US-Russia relations began to deteriorate in the late 1990s, for several reasons. In 1997 NATO offered membership to Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic; this expansion into eastern Europe by NATO was viewed by many as provocative to Russia and its interests. In 1999, NATO forces intervened in the Kosovo War by bombing Yugoslavia, a move opposed by Russia and undertaken without United Nations (UN) backing. The election of Vladimir Putin (1999) and George W. Bush (2000), followed by the September 11th terrorist attacks (2001), triggered pivotal shifts in Russian and American foreign policy. In December 2001, Washington outraged Moscow by announcing its intention to withdraw from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, one of the Cold War’s most significant arms reduction agreements. A further provocation arose in 2007 when the US began constructing missile defence systems in Poland.

Tensions eased somewhat between 2009-2012 under the presidencies of Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev. In April 2010 these two leaders negotiated and signed a new treaty reducing strategic nuclear weapons. Since then, Moscow and Washington have drifted apart due to disagreements over several issues and policies. These include ongoing disputes over American missile and defence systems in Poland; conflict over Western and Russian influence or interference in Ukraine and Georgia; anti-democratic reforms and human rights abuses within Russia; and, most recently, Russian intervention in the ongoing civil war in Syria. In 2016 the Russian government was accused of actively interfering in the US presidential election, through a campaign of Internet hacking, propaganda and disinformation. Some believe Russian interference in the election contributed to Donald Trump’s victory over Hillary Clinton, possibly as ‘payback’ for Clinton’s 2011 remark that Russia’s own elections were “neither free nor fair”. Donald Trump’s decision to launch two missile strikes against Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, a Putin ally, has further inflamed bilateral relations between Moscow and Washington.

A new ‘cold war’?

This breakdown in relations has prompted some commentators to claim the US and Russia have entered a new cold war. Many historians and political scientists consider this inappropriate for the modern context, however. The term “cold war” suggests similarities or analogies with the geopolitics and conditions that existed between 1945 and 1991. The current situation, however, is much more complex – and according to some experts, considerably more dangerous. Vladimir Putin is a nationalist whose policies seek to restore Russian influence in eastern Europe and central Asia. He views the United States as an aggressive imperialist power that threatens Russia militarily by placing missiles in Poland and expanding NATO. Washington has also interfered in Russia’s traditional sphere of influence by supporting pro-Western ideas and policies in Ukraine and Georgia. Many in the US, in contrast, see Putin as an anti-democratic and authoritarian ruler who models his leadership on that of Joseph Stalin. They view Putin as a dishonest autocrat willing to use underhanded methods from the Cold War, such as arming separatist movements in Ukraine, deploying mass campaigns of misinformation and ‘fake news’ on the Internet, or ordering the murder of journalists and whistleblowers to silence dissent.

“Our relationship to Russia ought to be among our closest. We both are committed to reduction of weapons of mass destruction. We both have immediate interests in combating terrorism. Russia stands on the border of five significant Islamic republics and shares concerns with us regarding stability in the Balkans and the Black Sea region. Russia possesses immense natural resources, supplies many of our allies in Europe, and offers an alternative source to precarious Persian Gulf supplies. Russia has world-class scientists, physicist, and mathematicians. We use Russian rocket propulsion systems to launch space missions and cooperate on manned space missions. Russia offers a vast market for American and Western products and services, an opportunity more appreciated by European enterprises than American ones. Further, Russia can be of considerable help to us and our allies in venues as disparate as Iran, North Korea, and the Middle East. In each of these cases, they stand to lose at least as much as we do, if not more, from war in these regions. We should treat the Russians as partners, not subordinates.”

Gary Hart, former US Senator

Evaluating the current situation should also look beyond individual leaders and perceptions of government. The United States and Russia have endured considerable economic and structural change in the past generation. The US has undergone significant de-industrialisation, shedding or scaling down labour-intensive industries such as car manufacturing, shipbuilding and coal mining. The US today is more focused on retail, technology, communications, healthcare, light manufacturing and service-based industries. The American economy remains the largest in the world, with a gross domestic product in excess of $US18 trillion, though it is carrying a national debt in excess of $US21 trillion. Russia has also de-industrialised significantly since the Cold War; Moscow now relies on its vast natural reserves of oil and gas to drive the Russian economy. Both the US and Russia are confronted with significant challenges in the medium to long-term. Among these challenges are population change, ageing infrastructure, resource depletion, an increasing reliance on imports and growing inequalities of wealth and income. Both nations will also wrestle with external conditions, such as the growth of China and the effects of climate change. These factors will shape US-Russia relations, for better or worse, as we progress further into the 21st century.

1. Almost 30 years after the Cold War, the United States remains the world’s largest superpower. Russia, in contrast, is a significant regional power, though no longer a global superpower.

2. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 gave rise to separatist or independence movements, terrorist groups and civil wars in places like Chechnya, Georgia and Ukraine.

3. US-Russia relations enjoyed a honeymoon period in the 1990s, as Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin negotiated cordially and signed trade and arms reduction agreements.

4. Relations then deteriorated as both nations adopted unilateral foreign policies. The expansion of NATO is one factor in worsening bilateral relations between the US and Russia.

5. Some believe the US and Russia are entering a new ‘cold war’, however, while tensions between Washington and Moscow undoubtedly exist, there are significant differences between the geopolitics and conditions of 1945-1991 and the current situation.

Content on this page is © Alpha History 2018-23. This content may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn & S. Thompson, “US-Russia relations since the Cold War”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/us-russia-relations-since-cold-war/.