The island nation of Cuba was another significant source of Cold War tensions. A close neighbour of the United States, Cuba is located less than 100 miles south of Florida. Though nominally independent, Cuba for decades relied on the US government for political support and American business interests, which propped up its small economy. This relationship collapsed in 1959 when a band of left-wing revolutionaries seized power in Cuba. Their leader, the outspoken and charismatic Fidel Castro, preached anti-imperialism and promised better lives for the Cuban people. Just as the Chinese Revolution allowed communism to take root in Asia, the Cuban Revolution brought it into America’s own backyard. Washington refused to recognise or deal with Cuba’s revolutionary government. As a consequence, Castro turned to the Soviet Union for support. This alliance led to the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, probably most dangerous superpower confrontation of the Cold War.

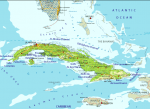

Cuba is the largest of the West Indies chain of islands, located in the Caribbean Sea. It is close to the United States mainland, a short stretch of water separating the Cuban capital Havana from Key West, Florida. Cuba was colonised by Spanish explorers in the early 1500s. Its sugar cane fields, worked by an army of slaves imported from western Africa, generated enormous profits for the Spanish Empire during the 19th century. In the second half of the 1800s, Cuba was wracked by uprisings and independence movements. Cuban independence was finally secured in 1898, during a war between the US and Spain. American forces occupied Cuba while a constitution and government were being constructed. When the constitution was finalised in 1901, Washington was given the constitutional authority to intervene in Cuban affairs. The US also received a permanent naval station at Guantanamo Bay in the island’s south-east. Cuba received its independence in May 1902 but its government and economy remained dependent on American support.

In March 1952 a Cuban officer, General Fulgencio Batista, led a military coup that seized control of the island. Batista’s coup prevented the election of left-wing nationalist Roberto Agramonte, who had been leading in the presidential polls. Batista’s regime justified its actions using Cold War fears, claiming a coup was necessary to thwart communist subversion. Batista was supported and recognised by the United States, which was then in the grip of McCarthyism. Batista was less concerned with suppressing communism, however, than consolidating and expanding his own power. He was reelected president in November 1954, though these elections were marred by threats, intimidation, widespread abstentionism and claims of vote-rigging. Political opponents and dissidents were threatened, beaten, tortured and driven into exile; a few vanished or were killed by Batista’s police. Meanwhile, Batista opened the Cuban economy for more American investment and tourism. Cuba became a virtual slave state, its sugar fields, mines, oil wells and ranches owned by American companies. The capital city Havana became a playground for America’s middle class, eager to escape the conservatism of American cities. By the late 1950s, Havana was awash with bars, casinos and brothels, a good deal of them run by American mobsters.

Batista’s slavish acquiescence to foreign interests saw millions of American dollars flow into Cuba – but most went straight into the pockets of the Cuban elites, government cronies and Batista himself. The government spent little on infrastructure, housing, health, education or social reforms. As a consequence, the living standards of ordinary Cubans stagnated during the 1950s. Opposition to Batista’s regime steadily increased. The most significant opposition group was led by Fidel Castro, a young Havana lawyer involved in left-wing politics. Outraged by Batista’s coup, Castro launched an underground movement that stockpiled weapons, published anti-Batista literature and recruited dozens of disaffected young students and workers. In July 1953 Castro’s rebels attacked a military base in Santiago de Cuba. This attack failed and Castro was arrested and imprisoned. Released in a general amnesty in May 1955, Castro resumed his revolutionary activities. He travelled abroad seeking advice and support, recruiting the Argentinian born militant Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara. From their mountain base in eastern Cuba, guerrilla units led by Castro and Che launched a series of guerrilla attacks on government forces. As unpopularity with Batista increased, so did volunteers prepared to fight under Castro and attack the government. By 1958, Cuba had become almost ungovernable. In late December that year Batista took flight, leaving the island with vast amounts of cash. Castro entered Havana in January 1959, claiming victory and control of the government.

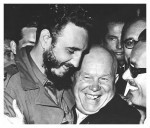

Castro became prime minister and the dominant figure in the revolutionary government. In the first weeks of his rule, Castro’s political intentions were uncertain. Washington and Moscow were aware of his affiliations but there were doubts about Castro’s commitment to socialism. Once in power, Castro refused to describe himself or his government as “socialist” or “communist”. He had no ties with Moscow and did not seek any initially. According to the memoirs of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, Moscow “had no idea what political course his [Castro’s] regime would follow… We had no official contacts with any of the new Cuban leaders and therefore nothing to go on but rumours”. Some in Washington labelled Castro a “watermelon”, green on the outside but red (communist) within. Others saw him as a simple-minded opportunist who, like Batista before him, could be bought off and controlled. In the first weeks of Castro’s rule, the new Cuban leader sought economic ties with Washington. Castro visited the US in April and held an awkward meeting with vice president Richard Nixon (the president, Dwight Eisenhower, instead chose to play golf). Castro proposed a Latin American version of the Marshall Plan, a program of Cuban reconstruction funded with American aid. The White House refused to acknowledge the new regime in Cuba, however, preferring to wait and see what Castro would do.

While Castro described his revolution as “humanist” rather than socialist, he soon adopted socialist policies. Castro’s regime launched a program of land reform, seizing control of large estates (albeit with compensation to existing owners). In 1960 Castro decreed that Cuban land could only be purchased by Cubans. He signed a trade deal with Moscow, exchanging Cuban sugar and foodstuffs for Soviet oil and industrial goods. Castro also embarked on a sweeping program of nationalisation, transferring privately owned companies into government hands. The first nationalisations occurred in the mining industry, which was dominated by American interests. After investing millions of dollars in Cuban mining, US companies had their land, materials and machinery seized, most without compensation. When American oil refineries in Cuba refused to process oil purchased from the Soviet Union, Castro responded by nationalising the refineries (June 1960). In total, more than 600 American owned companies were seized. Castro also cleaned up Havana’s seedier areas and red-light districts. American gangsters were thrown out of the city, their casinos and brothels closed, their henchmen thrown in prison or frog-marched to ports for deportation to Florida.

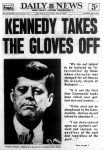

Castro’s seizure of American capital drew a hostile response from Washington. In July 1960 Eisenhower halted 700,000 tons of sugar imports from Cuba. Castro responded by nationalising American sugar refineries, as well as US telephone and electricity companies. In October, the US government banned all exports to Cuba, with the exception of medicine and essential food items. Washington blocked all Cuban sugar imports in December 1960. On January 3rd 1961, Eisenhower closed the American embassy in Havana and severed all diplomatic ties with Cuba. Behind the scenes, more radical strategies were being developed. In March 1960, Eisenhower approved a secret Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) plan to topple Castro by supporting counter-revolutionary guerrillas inside Cuba. Eisenhower committed $US13 million to the operation. When this failed, the CIA hatched a plan to overthrow Castro by supporting an amphibious invasion of Cuba by Cuban exiles. Operation Zapata, as it was known, was approved by Eisenhower and endorsed his successor, John F. Kennedy. In April 1961 around 1,500 counter-revolutionaries, trained and supplied by the CIA, landed in Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. Castro responded quickly to their incursion and the invaders were killed or captured within four days. The failed Bay of Pigs invasion caused considerable embarrassment for Washington, which had underestimated popular support for Castro.

The Bay of Pigs fiasco, along with internal plots and threats, caused Castro to grow suspicious, paranoid and intolerant of opposition. In late 1961 he declared Cuba a one-party socialist state. All newspapers, radio and television stations not owned or controlled by the government were closed. Fearing further CIA attacks on him or his regime, Castro banned American tourists from visiting Cuba. His fears were probably justified: the CIA’s Operation Mongoose included numerous plots to assassinate or cripple the Cuba leader, using everything from precision air strikes to poisoned milkshakes and exploding cigars. This American skulduggery drove Castro even closer to Moscow. He began accepting Soviet military equipment and expertise and consented to the installation of Soviet ballistic missiles on Cuba. Individuals who posed a threat to Castro’s regime – former allies of Batista, political liberals, radical academics and teachers, organised crime bosses – were imprisoned indefinitely and some were reportedly tortured. Castro’s regime targeted maricones (homosexuals), declaring them a subversive and socially disruptive group. Castro also provided support to other left-wing revolutionary groups around the world. During the 1960s and 1970s, he deployed 300,000 Cuban troops to fight in civil wars and support insurgencies in Africa, particularly in Angola and Ethiopia.

“Some things changed drastically with the fall of the Soviet bloc, which eliminated the trade and aid relationships that had sustained Cuba’s economy for three decades. To survive in the new international context the Cuban government implemented dramatic economic reforms, including opening to foreign investment, allowing some forms of private enterprise… and promoting tourism. It nevertheless maintained a commitment to preserving some of the key gains of the Revolution, especially the health and education systems.”

Aviva Chomsky, historian

For ordinary Cubans, the 1959 revolution delivered mixed outcomes. Castro’s regime came to power promising social equality and, in many respects, he delivered on this promise. The poorest strata of Cuban society benefited significantly from Castro’s reforms. The government provided subsidised housing, cheaper electricity and free healthcare and education. In 1961 teams of educators were deployed to peasant areas to combat illiteracy; by the mid-1960s Cuban illiteracy had been reduced from around 35 percent to less than five percent. Castro’s nation-state became well known for its healthcare, Cuba boasting more doctors per capita than Britain and most other Western nations. These improvements were concentrated in the cities, however, and were not uniform across the island. There was also a much darker side to Castro’s rule. The regime’s totalitarianism and attacks on political opponents, religion and homosexuals drew criticism from human rights groups. The collapse of communism in the late 1980s caused an economic slump and widespread shortages of consumer goods. In response, Castro permitted some economic and social liberalisation. In 2008 Castro, now in his 80s and in poor health, passed the presidency to his brother Raul and retired from public life. Relations between the US and Cuba led to bilateral talks, the resumption of tourism and the easing of trade embargoes. In July 2015, Washington and Havana agreed to restore diplomatic relations, ending more than 40 years of cold war between the US and Cuba. Fidel Castro died in November 2016, three months after his 90th birthday.

1. Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean, less than 100 miles from the United States. During the 19th century, Cuba was a Spanish colony known for its lucrative sugar production.

2. In 1952 General Fulgencio Batista led a military coup that seized control of Cuba. Batista’s regime was pro-American, corrupt and failed to improve the lives of most Cubans.

3. In January 1959 Batista was overthrown by an uprising led by Fidel Castro. The United States, uncertain of Castro’s ideology or intentions, refused to recognise his new regime.

4. Castro embarked on a program of nationalisation, seizing more than 600 American companies. There were reforms that benefited the Cuban people but also political violence and oppression.

5. In April 1961 a CIA-backed invasion via the Bay of Pigs failed to topple Castro. This triggered a prolonged Cold War between the US. Castro also sought aid and support from the Soviet Union, which precipitated the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

The UN Security Council urges negotiation between the US and Cuba (July 1960)

Soviet leader Khrushchev promises to support and defend Cuba (July 1960)

John F Kennedy’s address after the Bay of Pigs fiasco (April 1961)

Fidel Castro condemns US aggression against Cuba (April 1961)

Fidel Castro: Why does the US hate the Cuban Revolution? (February 1962)

A CIA appraisal of the political, economic and military situation in Cuba (August 1962)

Content on this page is © Alpha History 2018-23. This content may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn & S. Thompson, “Cuba under Castro”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/cuba-under-castro/.