East Germany was a socialist nation, formed in 1949 after the division of Germany. East Germany was, in many respects, the first child of the Cold War. When Germany was invaded by the Allies and the Soviet Union at the end of World War II, they agreed to occupy different zones. At this point, there was no plan to partition Germany into separate states. Amid the tensions and divisions of 1945-48, however, Germany’s post-war future became less certain. Events in Soviet-occupied eastern Germany placed it on a path of separate development. In April 1946 a pro-Soviet group led by Walter Ulbricht formed the Socialist Unity Party (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or SED). With the backing of Soviet military authorities, Ulbricht and the SED came to dominate the political landscape in eastern Germany. Events like the Berlin blockade of 1947-48 contributed to the widening gulf between the Allied and Soviet zones. These divisions culminated with the formation of an independent nation, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), on October 7th 1949. The Allies refused to recognise this new nation or its socialist government. The world, however, came to know it as East Germany.

East Germany had a population of just over 18 million people in 1949. Sandwiched between Allied-occupied West Germany and the Soviet bloc, the GDR became a focal point for Cold War tensions and intrigues. As a newly created nation, built atop the ruins of the Nazi state, East Germany became a proving ground for socialist government and policies. Walter Ulbricht became the most significant figure in this transformation. A fanatical communist, Ulbricht wore a beard like that of Vladimir Lenin while his leadership style was modelled on Joseph Stalin. Ulbricht’s power and profile grew steadily in the early 1950s. He served as deputy prime minister in the first months of the East German government, becoming general secretary of the SED in 1950 and the party’s first secretary in 1953. Stalin’s death in March 1953 raised questions about Moscow’s future policy on East Germany. Known to be a committed Stalinist, Ulbricht’s own position became uncertain.

On June 16th 1953 construction workers in East Berlin went on strike, in protest against increased work quotas and threatened pay cuts. The following day they were joined by 40,000 Berliners, most angry about austere economic conditions and a lack of political freedoms. The violence in East Berlin quickly spread to other parts of the country. East German police and soldiers, as well as Soviet troops, were deployed to halt the demonstrations and quash a potential uprising. This resulted in many deaths and injuries; estimates of those killed range between 80 and more than 500. The June Uprising, as it became known, convinced the Kremlin that a firm hand was needed in East Germany. Ulbricht was summoned to Moscow in July and given authority to purge the SED and crack down on dissidents. East Germany’s notorious secret police agency, the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit or ‘Stasi‘, had its leadership replaced and powers expanded. In addition to silencing troublemakers, Ulbricht also moved to placate the protestors. In the following months, he moved to alleviate food shortages, increase wages and pensions, and reduce the price of consumer goods and transportation.

East Germany remained economically backward in its first decade. There were several reasons for this. After World War II eastern Germany’s industrial sector, manufactured goods and raw materials were raided and seized by the Soviet Union, which claimed them as war reparations. More than half the region’s industrial capacity passed into Soviet hands between 1945 and 1949, and most of what remained was nationalised. Short of raw materials, East Germany’s remaining industries began to rely on expensive imports. After independence in 1949, East German exports could only be sold to Soviet bloc nations at fixed prices; they were unable to access the larger, more lucrative markets in West Germany or western Europe. In 1950 Ulbricht’s socialist government adopted a Stalinist economic policy that emphasised industrial production and collectivised agriculture. Workers were subject to rigorous work quotas and targets, while wages and prices were fixed by the state. This emphasis on industrial production and infrastructure led to a shortage of housing and consumer goods. There was a significant decline in living standards, which contributed to the Republikflucht: an exodus of people from East Germany. An average of 175,000 emigrants left the Republic each year between 1949 and 1953. The dire working and living conditions also contributed to the June 1953 Uprising mentioned earlier.

In the mid-1950s the East German government relaxed its economic policies. Its Stalinist Five Year Plan was replaced with a more moderate seven-year version, while greater emphasis was placed on producing consumer goods. These reforms were fairly superficial, however, and the East German economy showed only marginal signs of growth. Desperate to match the economic successes of West Germany, Ulbricht responded by speeding up the transition to full socialism. In the late 1950s, his government ordered more collectivisation of agriculture and the nationalisation of industries still in private hands. East Berlin also intensified its campaign of communist indoctrination and propaganda. These changes achieved little, except for another spike in the Republikflucht. In 1960 East Germany suffered its worst yearly exodus of citizens, losing almost 200,000 people across the border. By 1961, one in five East Germans had left the country. More than half this number were under the age of 30; many were well trained, educated or skilled workers. This ‘brain drain’ precipitated the 1961 Berlin crisis, the closure of East-West borders and the erection of the Berlin Wall.

In 1963 Ulbricht’s government announced the New Economic System (NES). The NES promised a mixed economy, combining decentralised economic management with elements of a market-based system. Price controls were relaxed and prices became more influenced by supply and demand. Greater autonomy was given to factory managers, while worker syndicates were allowed to participate in decision making. Work units were rewarded with incentives for meeting goals, rather than punishments for failing to meet them. The NES produced some short-term improvements – but again, these reforms proved too superficial to achieve lasting change. After almost two decades in power, Ulbricht had failed to fix the stagnating East German economy. When Willy Brandt became chancellor of West Germany in 1969 he began to hint at opening relations with East Germany. Ulbricht showed little interest and maintained his belligerent rhetoric towards the West. The old Stalinist, it seemed, was yesterday’s man. In 1971 the SED, with Moscow’s backing, quietly pushed Ulbricht from power. He remained as East Germany’s head of state but exercised no control over policy.

Ulbricht was replaced as general secretary by Erich Honecker, whose more flexible leadership contributed to a decade of Ostpolitik (sometimes referred to as the ‘German Détente‘). Honecker’s negotiations with Brandt led to the signing of the Basic Treaty (December 1972) and the restoration of diplomatic contact between East and West Germany. The East German border was opened for transit and tourism, while Honecker’s government negotiated trade deals with non-Soviet countries. Honecker also spent heavily to improve living conditions, particularly housing (more than a million new homes and apartments were constructed during the 1970s). Economic planning was reoriented to produce greater volumes of consumer goods, especially electrical items and everyday items like toiletries. In 1975 the government claimed that three-quarters of East German homes had a refrigerator, while two-thirds had a television and washing machine. East German living standards became the highest in the Soviet bloc. Yet despite these improvements, its citizens still lacked the diversity, choices and comforts available in West Germany.

“East German citizens [had] access to West German television, which showed them the freedom as well as the economic well-being of the West. The Honecker leadership initially did not take this cultural penetration very seriously. [But] constant exposure to the West German consumer culture had an insidious impact on East German society, encouraging East Germans to compare it to their own relatively run-down, deprived society.”

Minton F. Goldman, historian

Despite Honecker’s economic reforms, East German society in the 1970s and 1980s was oppressive, stagnant and uninspiring. East Germans continued to endure a dull routine of work, obedience and conformity. Most aspects of life were dominated by socialist values and expectations. Television, radio and the press were all state-owned. Cinema was popular but most movies were produced in the Soviet bloc. Food staples were in sufficient supply but most food was monotonous and bland. Involvement in religion waned, to the point where fewer than one in three East Germans identified as Christians. Workplaces, trade unions, cultural organisations, even sporting clubs were controlled or monitored by loyal socialists. The gatekeepers of this rigid socialist existence were the feared Stasi, aided by a network of spies and informers. This security apparatus was swift to crack down on political threats, potential troublemakers and criticism of the government. Unapproved political groups, cultural movements or individualism were all quickly suppressed. Most East Germans endured this lack of freedom by withdrawing into their private lives.

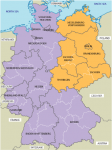

1. East Germany (the German Democratic Republic, or GDR) was an independent socialist state. It was formed in October 1949 from the Soviet occupation zone in Germany.

2. In its first two decades East Germany was governed by the Socialist Unity Party (SED) and Walter Ulbricht, a communist who modelled himself on Lenin and Stalin.

3. Ulbricht’s government imposed socialist economic policies, suppressed dissent after the June 1953 uprising, closed its borders and erected the Berlin Wall.

4. In 1971 Ulbricht was replaced by Erich Honecker. He developed a working relationship with West Germany, while moving to improve living standards in the GDR.

5. Despite Honecker’s economic reforms East German society stagnated, with political freedoms and individualism suppressed by the Stasi and government spies and informers.

Content on this page is © Alpha History 2018-23. This content may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn & S. Thompson, “East Germany”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/east-germany/.