Three events heralded the end of the Cold War: the fall of the Berlin Wall, the reunification of Germany and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. All came at the end of a tumultuous decade where ordinary people challenged the viability of socialism and socialist governments. The pressures they applied undermined and eroded political authority in Soviet bloc nations. With Moscow no longer demanding adherence to socialist policies, these governments relented, allowing political reforms or relaxing restrictions such as border controls. In East Germany, the epicentre of Cold War division, popular unrest brought about a change in leadership and the collapse of the Berlin Wall (November 1989). Within a few months, the two Germanys were rejoined after 45 years of division. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union was also in its death throes. After two decades of economic stagnation, the USSR was weakening internally. As the historian John Lewis Gaddis put it, the USSR was a “troubled triceratops”: it remained powerful and intimidating but on the inside its “digestive, circulatory and respiratory systems were slowly clogging up then shutting down”. Mikhail Gorbachev‘s twin reforms, glasnost and perestroika, failed to save the beast.

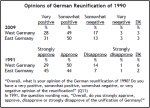

The demise of the Berlin Wall cleared the road to the reunification of Germany. Internal borders between East and West Germany, as well as those within the divided city of Berlin, were quickly removed. West German chancellor Helmut Kohl seized the moment by drafting a ten-point plan for German reunification, without consulting NATO allies or members of his own party. While most Germans welcomed the move, the prospect of a reunified Germany did not please everyone. It was particularly troubling for older Europeans with lingering memories of Nazism and World War II. British prime minister Margaret Thatcher was privately concerned about it, as were many French, Italians and indeed the Soviets. Israel, now home to thousands of Holocaust survivors, was the most vocal opponent of German reunification.

In March 1990, East Germany held its first free elections, producing a resounding defeat for the communists. The two German states stepped up their political and economic co-operation, agreeing to a single currency (the Deutschmark) in July 1990. Work was already underway on the formalities of reunification and the composition of a new German state. These questions were finalised by the Unification Treaty, which was signed in August 1990 and came into effect on October 3rd. A general election – the first all-German free election since 1932 – was held in December 1990. A coalition of Christian conservative parties won almost half the seats in the Bundestag (parliament), while Helmut Kohl was endorsed as chancellor. In the years that followed, Germany would dispel concerns about its wartime past by becoming one of the most prosperous and progressive states in Europe.

The Soviet Union passes into history

The Soviet Union remained the last bastion of socialism in Europe – but it too was rapidly changing. Gorbachev’s reforms of the mid-1980s failed to arrest critical problems in the Soviet economy. Soviet industries faced critical shortages of resources, leading to a decline in productivity. Meanwhile, Soviet citizens endured shortages of state-provided food items and consumer goods, giving rise to a thriving black market. Moscow’s big-ticket spending on the military, space exploration and propping up satellite states further drained the stagnating Soviet economy. More reforms in 1988 allowed private ownership in many sectors, though this came too late to achieve any reversal. It became clear that the Soviet economy could not recover on its own: it needed access to Western markets and emerging technologies.

The political dissolution of the Soviet Union unfolded gradually in the late 1980s. A series of reforms in 1987-88 loosened Communist Party control of elections, released political prisoners and expanded freedom of speech under glasnost. Outside Russia, the Baltic states (Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia) agitated for independence while separatist-driven violence was reported in Azerbaijan and Armenia. In early 1990, the Communist Party accepted Gorbachev’s recommendation that Soviet bloc nations be permitted to hold free elections and referendums on independence. By the end of 1990, the citizens in six states – Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Armenia, Georgia and Moldova – had voted to leave the Soviet Union. Ukraine, a region of considerable economic value, also declared its independence in July 1990. The Soviet republics that remained were given greater political and economic autonomy.

The August 1991 coup

“Many Russians sympathised with the plotters… because they approved of their motivation, that of preventing the Soviet Union from unravelling. After the initial euphoria… had died down, and people began to face the realities of a disbanded Soviet empire, disenchantment set in. Within a couple of years, the Yeltsin administration was itself pushing for a ‘reintegration’ of the former Soviet republics.”

Amy Knight, historianIn 1991 Gorbachev attempted to restructure and decentralise the Soviet Union by granting its member-states greater autonomy. Under Gorbachev’s proposed model, the USSR would become the “Union of Soviet Sovereign Republics”, a confederation of independent nations sharing a military force, foreign policy and economic ties. These proposed changes angered some Communist Party leaders, who feared they would erode Soviet power and bringing about the collapse of the USSR. In August 1991 a group of hardliners including Gorbachev’s vice-president, prime minister, defence minister and KGB chief, decided to act. With Gorbachev at his dacha in Crimea, the group ordered his arrest, shut down the media and attempted to seize control of the government. The coup leaders misread the mood of the public, however, which came out in support of Gorbachev. The coup collapsed after three days and Gorbachev was returned to office, though with his authority reduced. By Christmas 1991, the Soviet Union had passed into history. It was formally dissolved and replaced by a looser confederation called the Commonwealth of Independent States.

The death of the Soviet Union marked the curtain call of the Cold War. While communist regimes remained in China, North Korea and Cuba, the perceived threat of Soviet imperialism had been lifted from the world. Debate raged among commentators and historians about who was responsible for ending the Cold War. Some hailed Gorbachev and other Soviet bloc reformers as the architects of change and reform. Others credited strong-minded Western leaders like Ronald Reagan and Thatcher with bringing down the Soviet empire. Some believed communism was defeated by its own false promises: it was an unsustainable economic system that had collapsed from within. There was some truth in all three perspectives. In the tumultuous 1980s, however, ordinary people were the true engine of change. For decades citizens in the Soviet bloc had lived under oppressive one-party regimes and had little or no say in government. They were forced to work, denied the right to protest or speak and denied the choices available to their neighbours in the West. The final years of the Cold War were defined by these ordinary people, who risked their lives to rejoin the free world. Their determination and heroism were noted by novelist John Le Carre:

“It was man who ended the Cold War, in case you didn’t notice. It wasn’t weaponry, or technology, or armies or campaigns. It was just man. Not even Western man either, as it happened, but our sworn enemy in the East, who went into the streets, faced the bullets and the batons and said: ‘We’ve had enough’. It was their emperor, not ours, who had the nerve to mount the rostrum and declare he had no clothes. And the ideologies trailed after these impossible events like condemned prisoners, as ideologies do when they’ve had their day.”

1. Three significant events heralded the end of the Cold War: the fall of the Berlin Wall, the reunification of Germany and the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

2. The fall of the Berlin Wall prompted the removal of borders between East and West Germany, while West German chancellor Helmut Kohl began pushing for the reunification of the two states.

3. Despite opposition from some quarters, reunification proceeded during 1990. It was finalised by the Reunification Treaty (October) and free elections for a single Germany (December).

4. Beset by internal economic and political problems, the Soviet Union weakened during the late 1980s. After an unsuccessful coup attempt by hardliners, the USSR was dissolved in 1991.

5. There is much debate about the factors that brought the Cold War to an end. Some attribute it to Gorbachev’s reforms, strong leadership in the West or the unsustainability of socialist economic systems. The role of ordinary people in the late 1980s is also undeniable.

US intelligence paper: ‘The Soviet system in crisis’ (November 1989)

The German Unification Treaty (August 1990)

Communist hardliners justify their attempted coup to unseat Mikhail Gorbachev (August 1991)

The Minsk Agreement dissolves the Soviet Union (December 1991)

Content on this page is © Alpha History 2018. This content may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The end of the Cold War”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/end-of-the-cold-war/.