Bloody Sunday refers to the fatal shooting of 14 civilians by British soldiers in Derry on January 30th 1972. No single act of violence during the Troubles ignited more controversy. On the day in question, around 30,000 people had gathered in Derry to march against the policy of internment. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), supported by British paratroopers, contained the march to the Bogside area. There, for reasons that remain in dispute, a contingent of soldiers opened fire on civilian protestors. These shots struck 27 people, killing 13 instantly with one dying from his injuries weeks later. All of the dead were civilians, all were Catholics and seven were just teenagers. Their deaths rocked Northern Ireland and caused outrage and protest around the world. Both the British government and the British Army justified the shootings by claiming that several victims were carrying weapons. They also alleged that British paratroopers had come under fire from snipers in the crowd or nearby buildings. Westminster ordered an immediate investigation into the shootings. The inquiry was overseen by Lord Widgery and completed in just ten weeks. The Widgery Report backed the Army and found that some victims were carrying pipe bombs, a claim refuted by witnesses.

A protest against internment

Growing Catholic anger over internment provided the context for Bloody Sunday. In mid-1971 Northern Ireland’s Unionist government, led by prime minister Brian Faulkner, sought to curtail Republican paramilitary violence by arresting suspected Irish Republican Army (IRA) volunteers. These suspects would be questioned and detained without trial until the situation eased. Faulkner implemented internment after securing the reluctant approval of Westminster. In August 1971 the British Army launched Operation Demetrius, arresting and interrogating 342 suspected Republican paramilitary volunteers. They were held without charge or trial and detained in makeshift camps, under Northern Ireland’s Special Powers Act. Later, many internees claimed to have received brutal, even torturous treatment during their interrogation. Northern Ireland’s Catholics considered internment an act of sectarian persecution. No Loyalist paramilitary groups or individuals were interned in 1971. Many of the individuals interned were vocal civil rights campaigners rather than paramilitary operatives.

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) responded to internment with a series of protests. In September 1971 civil rights groups in Belfast encouraged Catholic families to protest against internment by refusing to pay rent or rates to government agencies. By the end of the month, an estimated 90 per cent of Belfast’s Catholic households were participating in the ‘rent strike’, costing local authorities more than £100,000. On January 2nd 1972 NICRA organised an anti-internment rally in Belfast, defying the Unionist government’s ban on marches and parades. Several thousand people gathered in the city centre and marched along the Falls Road; they were not hindered by police and the protest was completed peacefully. Another NICRA march, scheduled to be held in Derry in late January, was of greater concern to police. With its large population of working-class Catholics, Derry was a crucible of Republican radicalism; a march there had the potential for anti-government violence and property damage. Stormont and British security chiefs allowed the Derry march to proceed, however, barricades contained the protest to Catholic areas of the city and away from central Derry. A British Army contingent, the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment, was dispatched to Derry on the orders of Major General Ford, commander of British forces in Northern Ireland. The paratroopers were ordered to assist the RUC with containing the march and arresting troublemakers.

The fateful day

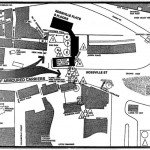

The anti-internment march began in the early afternoon of January 30th. Protestors set off from the Creggan Estate, some carrying the banner of the Derry Civil Rights Association. Estimates of the number of marchers vary considerably. According to NICRA and other civil rights groups, between 20,000 and 25,000 people participated in the January 30th protests. Government sources and the Widgery report claimed the number was much lower, perhaps as few as 3,000. NICRA organisers had planned to march through Catholic areas before stopping at Guildhall, the historic building that housed Derry’s city council, to hear several anti-internment speeches. At around 3.45pm the marchers approached Rossville Street in the Bogside. There they encountered British Army-manned barricades, blocking their way to Guildhall Square. Following instructions from NICRA organisers, most marchers proceeded up Rossville Street and Lecky Road to rally at Free Derry Corner. A contingent of radical protestors, mostly young males, took another route. They advanced on a roadblock on William Street, throwing stones and other small projectiles. Soldiers behind this barricade retaliated with tear gas and water cannon, while two observers were wounded with plastic bullets.

Many events from this point on remain in dispute. The first shootings occurred at around 3.55pm when a platoon of soldiers opened fire on several men in a disused building. Their shots struck two people: Damien Donaghy, 15, and John Johnston, 59; both were taken to hospital for treatment. About ten minutes later a larger contingent of soldiers moved into the Bogside, proceeding along William Street and then into Rossville Street, toward Free Derry Corner. According to testimony given at the Widgery tribunal, British Army Command had received reports of an IRA sniper active in the area. As a result, the 1st Parachute Regiment was given permission to enter the area. The situation deteriorated rapidly. The soldiers opened fire at around 4.10pm. The first fatality was John ‘Jackie’ Duddy, 17, shot in the chest near a block of flats on Rossville Street. According to witnesses Duddy was unarmed and running away from the advancing soldiers. A local priest, Father Edward Daly, was near Duddy when he was shot and remained by his side. Photographs and film footage of Daly giving Duddy the last rites, then leading a group of men carrying his body, are powerful visual relics from Bloody Sunday.

“Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!”

According to British Army evidence, the shooting continued for almost 30 minutes. During this time 21 soldiers fired 108 rounds. Most of the shooting occurred in four areas: around the Rossville Street flats, on Rossville Street itself and near two residential areas, Glenfada Park and Abbey Park. By the time shooting ended at around 4.40pm, 27 people had been struck by gunfire, 13 of them fatally. At least seven of the dead were shot from behind. One victim, 22-year-old James Wray, was shot dead at close range after being disabled by a shot to his legs; witnesses claimed Wray was pleading for assistance when the fatal shot came. Gerald McKinney, 35, was killed going to the aid of the fatally injured Gerald Donaghey, 17. Witnesses later testified that McKinney was holding his arms aloft and crying “Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!” when a bullet ripped through his torso. Another man, William McKinney, 26, was shot dead when he went to assist Gerald McKinney. Two other men – William Nash, 19, and Bernard McGuigan, 41 – were also killed going to the aid of injured people. McGuigan was shot through the head from behind while waving a white handkerchief. The death toll from Bloody Sunday rose to 14 in June 1972 when John Johnson, the first to be shot, died from complications from his injuries. Among the wounded were four more teenagers, including 18-year-old Alana Burke, whose pelvis was crushed when she was run over by a British military vehicle.

News of the Derry shootings was quickly flashed around Northern Ireland, Britain and the rest of the world. The Guardian’s Simon Winchester described the shootings as the culmination of a “tragic and inevitable Doomsday situation which has been universally forecast for Northern Ireland”. An editorial in The Times suggested that “the dreadful day’s work” would carry Northern Ireland to “a finally ungovernable condition”. The Republican and left-wing press declared Bloody Sunday an act of state-sanctioned terror. “This was murder”, screamed the front page of the Militant, a British socialist newspaper. The Republic of Ireland reacted strongly, recalling its ambassador to Britain and demanding an end to internment and “harassment” of Catholics in Northern Ireland. The apportioning of blame quickly followed. British Home Secretary Reginald Maudling addressed parliament on January 31st and claimed that soldiers had “returned the fire directed at them with aimed shots… on those who were attacking them with firearms and with bombs”. The Nationalist MP Bernadette Devlin – who had been present in Derry and saw the events first hand – called Maudling a “murdering hypocrite”, crossed the House of Commons floor and punched him in the face. On February 2nd a crowd of thousands advanced on the British embassy in Dublin and burned it to the ground.

Claims of a whitewash

“Clearly, the Widgery report was an elite-level attempt to explain away what happened and to fix the meaning of the event for the British population and wider international public. The ‘lies’ it contained were raised to the level of ‘truths’. In exonerating the soldiers of any wrongdoing, the report blamed NICRA – and by extension the victims who were killed – for the events of that day.”

Brian Conway, historian

Despite its assertions that the shootings were justified, the British government pledged to investigate the events of January 30th. The government handed this task to John Widgery, a career jurist who had overseen several inquiries. His appointment was immediately criticised. Some questioned Widgery’s capacity to act impartially: he was an Englishman with no special knowledge of Ulster, a former army officer, a life peer and a political conservative. Most commentators consider Widgery’s investigation a failure, if not a whitewash. The inquiry held just three weeks of hearings in Coleraine and Widgery submitted his final report after just 11 weeks. Though framed in guarded terms, the 45-page report exonerated the soldiers of any criminal wrongdoing. The firing of the paratroopers had “bordered on the reckless”, Widgery found, but “there was no general breakdown in discipline”. The soldiers acted in line with their understanding of orders given and the rules of the engagement, he said. Widgery cast much of the blame on NICRA and unidentified parties he believed fired on or threatened the soldiers. Despite a lack of conclusive evidence, the report implied some of the victims had been using or carrying weapons or improvised explosives.

If Bloody Sunday drove a stake into the heart of British-Nationalist relations, the one-sided Widgery Report provided the final hammer blow. The relationship between the British and Northern Ireland’s Catholics was now irretrievably shattered. British diplomat John Peck wrote later that the shootings “unleashed a wave of fury and exasperation… hatred of the British was intense”. Bloody Sunday helped transform moderate Nationalists into Republicans, pacifists into militants, the politically ambivalent into the purposefully outraged. According to Father Edward Daly, “people who were there on that day and who saw what happened were absolutely enraged by it and just wanted to seek some kind of revenge… many young people I [later] visited in prison told me quite explicitly that they would never have become involved in the IRA but for what they had witnessed, or heard of happening, on Bloody Sunday”. The best evidence of this can be found in the level of violence that followed the Derry shootings. A total of 476 people were killed in 1972, including the victims of Bloody Sunday.

The British apology

The Widgery report remained the British government’s official position on Bloody Sunday for more than 25 years. In 1998 prime minister Tony Blair ordered a second investigation into the shootings. This inquiry was overseen by Baron Saville, a British Supreme Court Justice. Saville’s investigation began in 2000 and lasted almost a decade, in contrast to the Widgery inquiry’s 11 weeks. Public and closed hearings heard evidence from hundreds of people, including soldiers, victims, eyewitnesses, politicians and Nationalist leaders. Saville’s report, published in June 2010, found that “immediate responsibility” for Bloody Sunday deaths lay with British soldiers and their “unjustifiable firing”. Nationalists in Northern Ireland hailed the Saville Report as a vindication of their position, while Unionists and British conservatives attacked the report as a political exercise. Days after the report was published British prime minister David Cameron apologised to the victims of Bloody Sunday, on behalf of the British government.

1. Bloody Sunday is a name given to the shooting of 27 civilians by British soldiers in Derry on January 30th 1972. Of those shot, 14 were killed or died from their injuries.

2. The shootings occurred during an anti-internment march organised by NICRA. The march was attended by several thousand people and subject to tight restrictions and policing.

3. Most of the shootings took place after British paratroopers entered Catholic areas of Derry, in response to reports of sniper fire.

4. News and images of the shootings caused outrage in Ireland and around the world. The British government responded by claiming the soldiers had responded to attacks.

5. A government inquiry, hastily completed in 11 weeks by Justice John Widgery, exonerated the soldiers and implied the victims had been carrying weapons or explosives.

BBC News: Soldiers open fire on protestors in Derry, killing 13 (January 1972)

A French photographer recalls the events of ‘Bloody Sunday’ (January 1972)

Alana Burke recalls the events of Bloody Sunday (January 1972)

The Guardian‘s post-Bloody Sunday editorial (January 1972)

The Widgery Report on the Bloody Sunday shootings (April 1972)

Thomas Kinsella’s Butcher’s Dozen: a poem about Bloody Sunday (1972)

The British Army issues new instructions on opening fire without warning (March 1973)

Tony Blair announces a new inquiry into Bloody Sunday 1972 (January 1998)

NICRA volunteer Charlie Morrison reflects on the events of Bloody Sunday (2002)

British prime minister David Cameron apologises for Bloody Sunday (June 2010)

Bloody Sunday (2012 film)

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebekah Poole and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Poole and J. Llewellyn, “Bloody Sunday 1972”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/bloody-sunday-1972/