Nazi attitudes toward God and organised religion were complicated. Contrary to popular opinion, Adolf Hitler was not an atheist. As a boy, Hitler was introduced to the Catholic faith by his devoutly religious mother. He was educated in a Catholic school and served as a choirboy in his local cathedral. Hitler drifted away from the church after leaving home. There is conflicting evidence about his religious views in adulthood. According to those closest to Hitler, he continued to identify as a Christian and made regular financial contributions to the church – though he never attended church or received communion. Hitler’s book Mein Kampf certainly contains many references to a divine creator. Hitler’s early speeches often mentioned God and emphasised the pivotal role of Christianity in German society. In an October 1928 speech Hitler said the Nazis “tolerate no one in our ranks who attacks the ideas of Christianity… in fact, our movement is Christian. We are filled with a desire for Catholics and Protestants to discover one another”. In another speech, the Nazi leader argued that:

“Today Christians … stand at the head of [Germany]. I pledge that I never will tie myself to parties who want to destroy Christianity … We want to fill our culture again with the Christian spirit … We want to burn out all the recent immoral developments in literature, in the theatre and in the press. In short, we want to burn out the poison of immorality which has entered into our whole life and culture, as a result of liberal excess.”

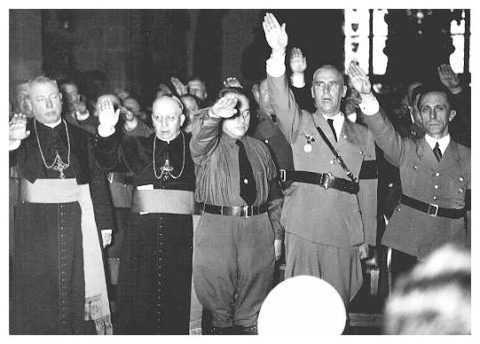

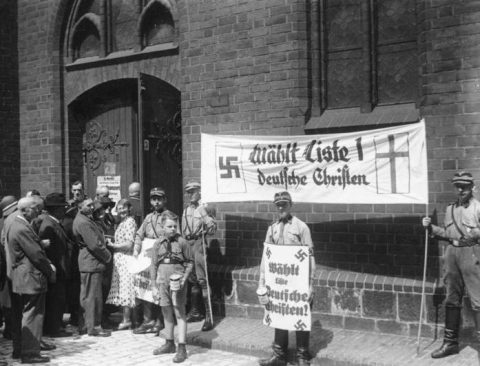

The spread of Nazi totalitarianism in 1933-34 forced German churches to take a position on Hitler and his followers. Some Protestant churches openly supported the Nazi movement. They pushed for the creation of a Reichskirche: a ‘state church’ loyal to Nazism and subordinate to the state. The Deutsche Kristen (German Christians) was the largest branch of German Protestantism and the most supportive of a Reichskirche. Deutsche Kristen leaders saw Hitler as a visionary, not unlike Martin Luther, the 16th-century founder of Protestantism. Hitler, they believed, had the potential to transform and revive German Christianity. There was also a strong anti-Semitic strain within the Deutsche Kristen; some of its leaders urged the rejection of Jewish texts and the expulsion of Christian converts with Jewish heritage. The leader of the Deutsche Kristen, Ludwig Muller, met with Hitler several times and promised his church’s support to the Nazis.

German Protestantism was a broad movement, however, and not all of its churches supported Hitler. Other Protestant leaders saw their religion as ‘above politics’; they refused to support or align with any party or to embrace nationalism or fascist values. In September 1933 several dozen delegates from German Protestant churches formed the Pfarrernotbund (Emergency League of Pastors) to resist the creation of a pro-Nazi state religion. The Pfarrernotbund also spoke out against Nazi racial policies, criticising the ‘Aryan paragraph’, a clause inserted into employment contracts to remove Jews from certain occupations. They elected a leader, Martin Niemoller, a Lutheran pastor from suburban Berlin. Within a few months, the Pfarrernotbund had the support of more than 7,000 individual Protestant clergymen. In May 1934 several Protestant churches united to form the Bekennende Kirche (Confessing Church), which also resisted attempts to ‘Nazify’ German churches. Members of the Bekennende Kirche were critical of Nazi policies during the mid-1930s, particularly anti-Semitic measures. The Nazis responded by arresting and detaining Pfarrernotbund and Bekennende Kirche figureheads, leaving the groups largely leaderless. Martin Niemoller was arrested by the Gestapo in 1938 and detained in Dachau until 1945. Other members of the Bekennende Kirche risked their lives by sheltering Jewish-born Christians, raising money and supplying fugitives with forged papers during the war.

The relationship between German Catholicism and the Nazi Party was conciliatory at first but quickly deteriorated. German Catholics, who had endured persecution during the late 1800s, had long desired a concordat – an agreement that guaranteed their rights and religious freedoms. After coming to power in 1933 Hitler expressed support for this idea. Hitler had no great desire to protect Catholic rights and privileges, however; he wanted a one-sided concordat to reduce the political influence of the Catholic church. In April 1933 Nazi delegates began negotiations with Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, the Vatican’s delegate to Germany and the future Pope Pius XII. As these negotiations progressed, the Nazis launched a wave of anti-Catholic intimidation, shutting down Catholic publications, breaking up meetings of the Catholic-based Centre Party and throwing outspoken Catholics into concentration camps. As Pacelli later put it, the negotiations proceeded with a pistol at his head.

- Catholics were guaranteed freedom of religious belief and worship in Nazi Germany

- The Vatican retained the right to communicate with, and preach to, German Catholics

- The church retained the right to collect ecclesiastical taxes and donations

- Catholic bishops had to swear an oath promising to “honour” the government

- Catholic organisations such as charities, schools and youth groups were protected

- Catholic clergymen and delegates could not be members of, or speak on behalf of, political parties

“The Catholic Church … consistently maintained an anti-Nazi attitude. In several parts of Germany, Catholics were explicitly forbidden to become members of the Nazi Party, and Nazi members were forbidden to take part in church funerals and ceremonies. The bishop of Mainz even refused to admin NSDAP members to the holy sacraments.”

Jane Caplan, historian

Pacelli and his colleagues were not optimistic about the Reichskonkordat. They knew Hitler and his followers would not protect the church or its rights. It was, as put by historian Hubert Wolf, “a pact with the devil – no one had any illusions about that fact in Rome – but it [at least] guaranteed the continued existence of the Catholic Church during the Third Reich”. The Nazis began flouting the terms of the concordat while the ink on it was still drying. In December 1933 Berlin ruled that all editors and publishers must belong to a Nazi ‘literary society’; this decree effectively gagged Catholic publications and prevented church leaders from protesting breaches of the Reichskonkordat. Between 1934 and 1936 the Nazis shut down several Catholic and Lutheran youth groups; many of their members were absorbed into the Hitler Youth. Catholic schools were closed and replaced with ‘community schools’, run by Nazi sympathisers. A year-long campaign against Catholic schools in Munich in 1935 saw enrolments there drop by more than 30 per cent.

Direct attacks on the church and its members escalated in 1936. Dozens of Catholic priests were arrested by the Gestapo and given show trials, accused of involvement in corruption, prostitution, homosexuality and paedophilia. Anti-Catholic propaganda appeared on street corners, billboards and in the pages of the notorious anti-Semitic newspaper, Der Sturmer. This campaign produced a defensive response. In March 1937 Pope Pius XI released an encyclical (circular letter) titled Mit brennender Sorge (‘With burning concern’). It was written by Michael von Faulhaber, archbishop of Munich, in consultation with other Catholic leaders, including Cardinal Pacelli. Mit brennender Sorge criticised Nazi breaches of the Reichskonkordat, condemned Nazi views on race and ridiculed the glorification of politicians and the state. “Whoever exalts race, or the people, or the state, or a particular form of state… above their standard value and raises them to an idolatrous level”, the letter said, “distorts and perverts an order of the world planned and created by God.” More than 250,000 copies of the encyclical were distributed to German churches, to be read to congregations from the pulpit. This infuriated Hitler and the Nazi response was swift and intense. Gestapo agents raided churches and printers, seizing and destroying copies of the encyclical wherever they could be found. Propaganda and show trials against Catholic clergy gathered pace through 1938-39 and several priests ended up behind the barbed wire at Dachau and Oranienburg.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses were another religious group persecuted by the Nazis. Germany had around 15,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1933. Their religious beliefs prevented the Witnesses from swearing allegiance to a government or secular power; they also refused to submit to military conscription or perform the Nazi one-armed salute. In April 1933 Nazi paramilitary groups shut down several Jehovah’s Witness offices and buildings. By the middle of 1933, the Jehovah’s Witness religion had been formally banned in most parts of Germany. Individual Witnesses were sacked from jobs in the public and private sector; others were refused access to state welfare or pensions. They could restore these rights by renouncing their religion and pledging allegiance to the Nazi state, though few did. The Gestapo began compiling a register of all Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1936. By 1938 several thousand had been arrested and transported to concentration camps. Inside the camps, they were identified by a triangular purple patch on their uniform. About 10,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses were detained in camps between 1938 and 1945. Around one-quarter of this number were either murdered or succumbed to starvation or disease.

1. Nazi attitudes toward religion were complex. While most of the Nazis were Christian or supported Christian values, they were strongly opposed to the political influence of churches, which threatened the Nazi program.

2. Hitler was not an atheist. He was raised as a Catholic and his writings and speeches often contained references to God, Christianity and religion, highlighting and praising their role in German society.

3. German Protestant churches were divided about Nazism. A strong faction in German Protestantism pushed for a Nazified ‘state religion’, while other Protestant leaders opposed the integration of religion and politics.

4. The Nazis signed a concordat with the Catholic church in July 1933, however it was a political ploy to minimise the church’s political influence. The Catholic church was allowed to continue in Nazi Germany but the terms of the concordat were often violated.

5. The Nazis also intimidated and marginalised Germany’s 15,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses, who refused to swear loyalty to Hitler or undertake military service. Large numbers of Jehovah’s Witnesses were detained in concentration camps, where around one quarter died.

© Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Religion in Nazi Germany”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/nazigermany/religion-in-nazi-germany/.