Nazi economic policy was largely based on fascist economic theories. In fascism, resources and production are managed for the greater benefit of the state, rather than to increase profit, wages or standards of living. Fascist governments control production and manufacturing, dictating what is produced and for what purposes. There is also considerable government control over the allocation of resources, such as land and raw materials. Unlike socialism, fascism is not opposed to private ownership of capital, provided that business owners are co-operative and do not resist state control. In fascist economic systems, such as Mussolini’s Italy, economics is considered a partnership between the state and private-owned corporations. Fascism is, however, hostile to unions, contending that workers should put the interests of the state before their own petty needs. Fascism also tends to encourage autarky (economic self-sufficiency) rather than foreign trade.

Adolf Hitler himself was not particularly interested in economic theory. His speeches of the 1920s contained almost no reference to economic policy, other than vague statements about ceasing reparations payments and restoring German industry. Once in power, Hitler played little part in formulating policy or contributing to German economic recovery. He instead relied on a group of advisors, some of whom were non-Nazis, to form policy in line with his broad goals. One of these advisors was Hjalmar Schacht, a former member of the German Democratic Party (DDP) who had been president of the Reichsbank during the late 1920s. Another important figure was Robert Ley, who was put in charge of the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (the DAF, or ‘German Labour Front’) which co-ordinated Germany’s workforce. Together these men implemented economic reforms which achieved impressive results, at least on the surface.

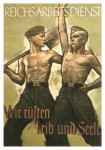

At the core of the ‘German economic miracle’, as Hitler described it, were work programs and re-armament. The Nazis initiated massive spending programs to stimulate the economy, generate jobs and encourage economic growth. In July 1934 the government formed the Reichsarbeitsdienst (the RAD, or ‘National Labour Service’). The RAD attacked unemployment by conscripting out-of-work Germans into vast work teams. RAD workers were given an armband, a shovel and a bicycle, then sent to wherever public works, construction, clearance or agricultural labour were needed. One of the earliest RAD programs was the construction of massive autobahns: hundreds of miles of freeway connecting Germany’s major cities. These autobahns had a positive effect on the German car industry, which also flourished from the mid-1930s. In 1937 Hitler established Volkswagen, a state-sponsored company to produce cheap cars for German families.

Huge public works schemes, particularly in construction, were organised by RAD and DAF. By 1936 two million Germans were working in construction industries, almost three times the number when Hitler became chancellor in 1933. These projects re-built or renovated many of Berlin’s public buildings. By 1936 there was more or less full employment in Germany, though of course, the Nazis manipulated these statistics to give the appearance of an improving economy. Women and political opponents were not counted in the unemployment figures, for example; nor were German Jews, many of whom had been banned from their occupations.

“Ideology played a secondary role in Hitler’s economic policies. For reasons of expediency, Hitler did not attempt to nazify the economy. Instead, he left the actual running of the economy to experts in business and industry, while instituting a large amount of control from above to force cooperation and compliance with his economic objectives. So long as they cooperated, big business and industry profited by this relationship. In essence, the German economy under Hitler was neither totally free nor totally controlled.”

Joseph Bendersky, historian

Another factor in German economic growth was re-armament. Hitler had initiated programs to re-arm and expand the Reichswehr, in defiance of the Treaty of Versailles, shortly after coming to power. He commissioned new battleships and submarines and tasked Hermann Goering with building a new Luftwaffe (air force). In 1935 Hitler ordered the Reichswehr be re-formed as the Wehrmacht: he introduced compulsory military service and increased the army to 550,000 men. Re-armament became a national economic priority – but this was problematic since German industries were still heavily reliant on imported raw materials. In 1936, at the Nuremberg party conference, Hitler announced a new economic program: the Four-Year Plan. “Germany must reach full independence from abroad in all raw materials that can be produced by German skills, by our chemistry, by our mechanical industries and our mines”, Hitler told party delegates. But the Four-Year Plan was also a secret challenge to Nazi economic managers to initiate Aufrustung (the code-name for re-armament and war preparations).

Deputy leader Herman Goering was appointed by Hitler to oversee the Four-Year Plan and its armament program. The German economy underwent significant changes during this period. Oil and coal refineries were constructed; so were factories for the recycling, refining and smelting of steel and aluminium. Scientists devised synthetic or artificial substitutes for materials and goods Germany could not produce herself. One of the more successful of these was a technique for synthesising petrol from coal. Alternatives were even created for the consumer market, to reduce imports. Known as ersatz goods, they included replacements for cotton, rubber and heating oil. Coffee was produced from ground roasted acorns; mint and raspberry leaves were used to make tea. But in spite of these changes, Germany was still far from self-sufficient. By 1939 it was still importing 33 per cent of its raw materials and 20 per cent of its food. Enough had been done to facilitate the expansion of the German military and its partial re-armament. Spending on arms doubled in just one year, as Goering ordered the retooling of factories to produce weapons, munitions, vehicles and other military equipment.

1. Hitler played only a minor role in the economic recovery of Germany, relying instead on advisors and bureaucrats.

2. Rearmament was a critical part of this recovery – the government ignored reparations to fund military spending.

3. There were large public works programs, such as construction, roads and autobahns, to reduce unemployment.

4. An attempt to make Germany self-sufficient and end its reliance on imports was only partly successful.

5. In 1936 Hitler ordered a Four-Year Plan, overseen by Goering, to further militarise production and prepare for war.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Nazi economic recovery”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/nazigermany/nazi-economic-recovery/.