Mao Zedong was sidelined from political power and policy-making in the early 1960s, however, he still retained control of ideology and propaganda. In 1963 Mao launched the Socialist Education Movement, an attempt to restore the People’s Communes, but this move was short-circuited by Liu Shaoqi. Frustrated by this failed attempt to exert control over policy, Mao blamed opponents and manipulators within the party, claiming that “someone is shitting on my head”. Next, Mao turned his attention to the people. In 1964 the Chairman and his acolytes launched three signification ‘Learn from’ campaigns, each accompanied by a wave of rhetoric and propaganda. These programs, the best known of which was ‘Learn from Lei Feng’ campaign, promoted Mao’s socialist agenda and values through the tales of successful people and places. Chinese people were urged to study these examples and replicate these figures in their own work, their life and their attitude to the party.

The most enduring of these campaigns was ‘Learn from Lei Feng’. In August 1962 Lei Feng, a 21-year-old People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldier, was killed by a toppling telegraph pole while working in Liaoning province. The death of a young soldier carrying out his duty was tragic, if mundane – yet it gave rise to one of the most prolific and successful propaganda campaigns of the new order. According to propaganda released in March 1963, Lei Feng’s diaries showed a young man of outstanding character and commitment to the revolution. His diaries were published for public scrutiny, said party chiefs, because they provided valuable lessons for all Chinese people. According to government accounts, Lei Feng’s life had mirrored the fate of 20th century China. His family suffered at the hands of greedy landlords, the treacherous Guomindang and bloodthirsty Japanese invaders. Despite these hardships, Lei became a diligent worker and demonstrated unflinching loyalty to Chairman Mao, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), his community and his comrades. In one entry in his diary, Lei Feng wrote:

“November 8th 1960, I will never forget this day, when I had the honour of being made a member of the great Chinese Communist Party, thus realising my highest ideal. Oh, how thrilled my heart is! It is beating wildly with joy. How great the party is! How great Chairman Mao is! When I was struggling in the fiery pit of hell and waiting for the dawn, it was you who saved me, gave me food and clothing, and sent me to school… Now I am a party member and a servant of the people. For the freedom of mankind and the cause of the party and people, I am willing to climb the highest mountain and cross the widest river, to go through fire and water. Even at the risk of death, I will remain forever loyal to the party…”

Not only did Lei perform his duties as a soldier, he volunteered his spare time to helping others – including his colleagues and peasants. He did sewing for his fellow soldiers, gave up food for those who were hungry and donated part of his wages to needy peasants. According to one story, Lei was granted several days’ furlough from the army but instead volunteered at a local commune, where he helped by shovelling and carting hundreds of pounds of manure. Lei became both a martyr and a symbol of the new China; his selflessness and devotion to socialism were held up as a shining example for all Chinese people. In 1964, with the Cultural Revolution imminent, the Lei Feng campaign began to feed the building cult of Mao. Exponents of Lei Feng propaganda used it to demand complete loyalty to the Chairman and ‘Mao Zedong Thought’. The story of Lei Feng was used to embarrass and condemn suspected Rightists and ‘capitalist roaders’ who, by comparison, were said to lack Lei’s character. The ‘Learn from Lei Feng’ program, initially a push for people to perform minor good deeds and be content with few material possessions, developed a more sinister agenda. The ‘Learn from Lei Feng’ model survives in China today, albeit with less intensity.

Some ‘Learn from…’ campaigns focused not on individuals but on work teams or communes. One prominent campaign was ‘Learn from Daqing’, launched by Mao in 1964. Daqing was a cold and barren wasteland in Heilongjiang province, in China’s remote north-east. In 1959 a group of drillers battled the hostile conditions and struck oil in Daqing. It became one of China’s most prolific and lucrative oil fields, and by the end of 1963 was producing five million tonnes of oil a year. The discovery of Daqing’s vast reserves allowed China to become self-sufficient in oil, ending its reliance on foreign imports. The successes of Daqing were not given prominence until 1964, when a glowing, if not gloating Mao unveiled them to the nation. He offered the oil discoveries in Daqing as a challenge to workers in other industrial sectors. The motto of this campaign became: “In industry, learn from Daqing”.

Just as the Lei Feng campaign had its hero, so too did ‘Learn from Daqing’, and his name was ‘Iron Man’ Wang (1923-70). Born Wang Jinxi in Gansu province, he received only a basic education and was forced into child labour, before joining the oil industry as a teenager. According to CCP propaganda, unconfirmed by other sources, Wang was a “model worker” who met Mao Zedong in Beijing in the 1950s and promised to find him more oil. By the late 1950s, Wang was a drill team foreman working in north-east China. Wang’s teams were known for their efficiency and high production, while Wang himself was praised for his hard work, toughness and decision making under pressure (hence the nickname ‘Iron Man’). According to legend, it was ‘Iron Man’ Wang and his team who found the first significant oil deposits in Daqing. A famous photograph, possibly staged, shows Wang leaping into a slurry pit to plug the gushing oil with his own body.

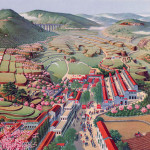

In a similar vein to ‘Learn from Daqing’ was ‘Learn from Dazhai’. This campaign focused on the achievements of the Dazhai commune during the Great Leap Forward. Until the late 1950s Dazhai was a struggling community of 80 or so peasant families in remote Shanxi province. Its land was hilly and rocky, and was difficult to access and farm. Because of this it had traditionally produced low yields. In the late 1950s peasants in Dazhai collectivised and formed their own commune. With assistance from party cadres they obtained more arable land by constructing terraces and clearing mountainous forests. According to communist rhetoric, Dazhai was a shining success story of the Great Leap Forward. The people of Dazhai not only survived the Great Famine, they increased production of maize to a reported 9,000 kilograms per hectare. The production figures coming out of Dazhai caught the attention of the CCP hierarchy. In 1964 Zhou Enlai sent his agriculture minister to Dazhai on a study visit. “Dazhai is a model of self reliance”, the minister reported, “[it is] our banner on the national agricultural front”.

“In traditional China, tales of individuals who exemplified extremely virtuous or self-sacrificing behaviour formed a regular part of moral education. Young people were instructed in the tales about filial sons and steadfast women; adults enjoyed stories and plays in which characters were either paragons of virtue or totally evil… in the last three decades, the one who has become best known undoubtedly is Lei Feng.”

Patricia Buckley-Ebrey

The ‘Learn from Dazhai’ campaign can be traced from this point. Dazhai was woven into Communist Party rhetoric, particularly speeches or announcements about agricultural policy or collectivisation. Later, in the autumn of 1970, Mao Zedong escalated the ‘Learn from Dazhai’ campaign further, launching a wave of written and visual propaganda. “Dazhai is a red flag supported by the great leader, Chairman Mao… We must speed up the promotion of the Dazhai experience”, the People’s Daily told its readers in September 1970. Posters showed how Dazhai’s peasants had transformed their region from rocky hills and gullies into productive terraces and farmland. Dazhai became a focal point for Chinese agriculture, hosting party meetings, economic conferences, study teams and thousands of curious visitors. Dazhai’s commune foreman, Chen Yonggui, was moved to Beijing and given a seat on the CCP Politburo – despite being illiterate and having no experience in politics.

As with most propaganda, several aspects of the ‘Learn from’ campaigns were exaggerated, dubious or downright false. There are strong doubts, for example, about the authenticity of material attributed to Lei Feng. For an anonymous soldier of low rank, killed in his early 20s, Lei Feng left an abundance of photographs and personal writing, all of it in line with party values. Many contemporary scholars believe much of the material written by or about Lei Feng is a concoction. Lei is “the yeti of Chinese Communist history”, writes Evan Osnos, “a creature widely described and occasionally photographed but perhaps nonexistent”. Much of the ‘Learn from Dazhai’ mythology was also a sham. Dazhai’s economic success during the Great Leap Forward was greatly exaggerated by false reporting. When the ‘Learn from Dazhai’ campaign commenced, Mao pumped vast amounts of money into the region to maintain an appearance of innovation, productivity and success. The successes in Daqing were not as fraudulent – though they were derived more from geological good fortune than human endeavour. In the end, there was not much to ‘learn from Daqing’, other than to find a lucrative oilfield.

1. In 1963 Mao launched the Socialist Education Movement, an attempt to restore the People’s Communes. The failure of this movement frustrated Mao, who was unable to exert much influence over policy.

2. Instead, Mao turned his attention to propaganda campaigns. The first ‘Learn from’ campaign focused on the life, conduct and attitude of Lei Feng, a supposedly devoted PLA soldier killed in 1962.

3. ‘Learn from Daqing’ celebrated the success of ‘Iron Man’ Wang and his fellow oil drillers, who tapped a major oil field in remote Daqing, allowing China to become self-sufficient in oil.

4. ‘Learn from Dazhai’ hailed the achievements of a Shanxi commune during the Great Leap Forward. Its alleged successes became a model for agricultural innovation and progress.

5. In reality, these propaganda campaigns were based on exaggerated or doubtful information. Many experts have questioned the authenticity of Lei Feng’s diaries and reported successes of Dazhai.

© Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Glenn Kucha and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

G. Kucha & J. Llewellyn, “The ‘Learn from’ campaigns”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/learn-from-campaigns/.

This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.