In 1950 the newly formed People’s Republic of China became embroiled in a significant conflict in Korea. Communist China was not prepared for another war – particularly one involving the United States, Great Britain and other Western powers. Its economy was already disorganised and exhausted by years of war against the Japanese and the Nationalists. But with the Korean peninsula on China’s doorstep, and a communist ally threatened by foreign invasion, Mao Zedong could not ignore the unfolding crisis there. China’s involvement in the Korean War heightened domestic security concerns, stretched the already depleted national economy and risked provoking the West into an all-out war with China. The war ended in stalemate and Mao hailed the performance of Chinese soldiers in Korea – but their involvement had serious ramifications for China’s foreign relations.

Korea is a peninsula region with strong historical ties to China. Most of Korea’s only land border is shared with Manchuria (northern China). The Manchu invaded and subjugated Korea in the 17th century, as they had done with China. By the late 19th century the Korean peninsula was the focus of imperial rivalry between Russia and Japan, which to the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-5. Japan annexed Korea in 1910 and ruled there until advancing Soviet and American forces pushed them out late in World War II (1945). In September 1945 the Korean peninsula was occupied by Soviet forces in the north and United States forces in the south. This division was intended as a temporary measure, lasting four years, after which an independent Korean government was to be elected. But the Soviets and Americans, driven by ideological interests and Cold War tensions, encouraged the formation of separate governments. In the mid-1940s the peninsula began to harden into two different political entities. Despite United Nations involvement North Korea and South Korea became independent nation-states in 1948.

The leader of North Korea was Kim Il-Sung, a native Korean who had served in the Soviet Union’s Red Army during the war. Backed by Moscow, Kim initiated a program of land reform and redistribution that proved popular with local peasants. He used political coercion, violence and murderous purges to eliminate his political opposition. Kim also claimed sovereignty over the entire Korean peninsula and regularly threatened war and invasion against South Korea. Tensions between the two Koreas increased in 1949-50, as their leaders engaged in aggressive political rhetoric. They also fortified the 38th parallel border and increased their military presence there, leading to cross-border shootings and skirmishes. In June 1950, one of these border clashes sparked a full-scale invasion of South Korea by the North Korean People’s Army (KPA).

Kim Il-Sung’s decision to invade South Korea was endorsed by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Within days of the invasion, US president Harry Truman ordered American troops into South Korea to resist the communist invasion. Meanwhile, a United Nations resolution condemned the invasion and ordered North Korea to withdraw. When they failed to do so, a 16-nation multilateral military force – about half of which was American – was mobilised to help defend South Korea. Their involvement proved successful early and the North Koreans were quickly pushed back over their own border. The US commander in Korea, General Douglas Macarthur, made public statements calling for a war with China, arguing that Chinese bases were supplying the North Koreans. This heightened tensions in Beijing and paved the way for Chinese involvement. Mao Zedong, fearing that American forces would overthrow Kim Il-Sung and occupy the whole Korean peninsula, decided to act.

“We are still convinced that dispatching our troops to Korea would be beneficial to us. In the first phase of the war, we may concentrate on fighting the puppet [South Korean] army, which our troops are quite capable of coping with. We may open up some bases in the mountainous areas north of Wonsan and Pyongyang. This will surely raise the spirits of the Korean people… The adoption of the above-mentioned active policy will be very important to the interests of China… If we sent none of our troops and allowed the enemy to reach the banks of the Yalu River, the international and domestic reactionary bluster would surely become louder…”

Mao Zedong, October 1950

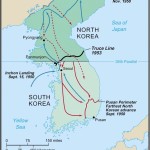

After deliberations with his fellow leaders, some of whom did not support Chinese involvement in Korea, Mao made his move. In the summer of 1950, he authorised the mobilisation of the People’s Volunteer Army (PVA), a military force Mao claimed to be separate from China’s official army and therefore not under state control. At its peak, this ‘unofficial’ army contained in excess of two million Chinese soldiers, supposedly volunteers. Mao also sought help from Moscow, however, Stalin had no taste for a war with the US and gave only limited assistance. On October 19th 1950 the US-led coalition captured the North Korean capital, Pyongyang, and continued its push further north. On the same day, regiments of the PVA crossed the Yalu River and entered North Korean territory. The first battle between Chinese and United Nations forces followed six days later. With a quarter of a million men, the PVA’s numerical superiority forced UN forces back over the 38th parallel. At this point, General Macarthur mused publicly about using nuclear weapons on China. He was later sacked by President Truman.

From mid-1951 the fighting in Korea eased, as both sides sought to hold territory rather than capture it. China’s leaders hoped that dragging out the conflict might cause Western forces to abandon South Korea – but the PVA in Korea was itself stretched to breaking point. The Chinese volunteer soldiers were not only suffering heavy casualties from American bombers, they were critically short of weapons, munitions and supplies. Thousands of PVA soldiers in Korea died from malnutrition, inadequate medical care and freezing winters with sufficient blankets or uniforms. PVA leader Peng Dehuai fumed about these shortages but they were a symptom of China’s parlous economic condition in the early 1950s. After a drawn-out series of peace talks, an armistice to end the fighting in Korea was signed on July 27th 1953. The border between the two Koreas came to be strengthened by a four-kilometre buffer known as the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ). A formal treaty was never signed, which means the Korean War is still ongoing today.

The Korean War had mixed results for Mao Zedong and the People’s Republic. The conflict killed almost two million soldiers and civilians; between 150,000 and 400,000 of the dead were Chinese. The war produced no tangible change in sovereignty, government or territory on the peninsula – yet Mao considered China’s involvement to be a success. China had confronted the United States, the world’s preeminent military power, and held its own. Despite their lack of supplies and heavy losses, Chinese troops had performed creditably against modernised Western military forces. They had defended North Korea and kept the US at arm’s length from important industrial sites in northern China. The Korean War also enhanced Mao’s reputation, both as a military strategist and a communist leader prepared to stand up to the West. China’s involvement in the war also entailed some significant costs. At American urging, the United Nations passed a resolution condemning the People’s Republic as an aggressor state. From 1953 ‘China’ was represented at the UN by Jiang Jieshi’s Taiwan-based government (the People’s Republic of China was not admitted to the UN until 1971). Communist China was also subjected to years of non-recognition, international isolation and trade embargoes. Mao also suffered a personal loss in the Korean War: his eldest son Mao Anying was killed by an American air raid in November 1950.

1. The Korean War was a conflict fought between June 1950 and July 1953. It saw involvement from North and South Korea, the People’s Republic of China and a United Nations force led by the United States.

2. The conflict was started by Soviet-backed North Korea and its leader, Kim Il-Sung, who ordered an invasion of US-backed South Korea in June 1950.

3. A coalition of United Nations forces became involved and push North Korean forces back to the Chinese border. After some equivocation, Mao deployed around 250,000 Chinese volunteers fighting as the People’s Volunteer Army.

4. The Korean War eventually ended as a stalemate, with borders and territory largely unchanged. Around two million soldiers and civilians were killed, between 150,00 and 400,000 of whom were Chinese.

5. Mao considered the war successful because it showed the new People’s Republic as a bold and capable fighting force, willing to stand against the Americans – but it also entailed years of non-recognition, international isolation and trade embargoes.

© Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Glenn Kucha and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

G. Kucha & J. Llewellyn, “The Korean War”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/korean-war/.

This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.