Internment is the practice of detaining or imprisoning individuals without a trial or due process. It is usually implemented during a period of war or conflict; those interned are suspected of working with or aiding the enemy. Internment was controversially imposed by the Northern Ireland government during the Troubles. It was introduced in August 1971 by Unionist prime minister Brian Faulkner, under the auspices of the Special Powers Act. It was not the first use of internment in Irish history, nor was it entirely unexpected. By removing and isolating paramilitary leaders Faulkner’s government hoped to stem sectarian violence. Poor planning and implementation led to internment having the opposite effect. The arrest and heavy-handed treatment of interned persons, particularly Catholics, generated antipathy towards the government and worsened an already volatile situation.

Rising paramilitary violence

The context for internment was the growth and increased activity of paramilitary groups. After its formation in December 1969 the Provisional IRA spent the next 12 months recruiting, training and acquiring weapons. By early 1971 the Provos were ready to intensify their campaign against British security forces. On February 6th 1971 a ricochet from a Provisional IRA machine gun struck and killed Robert Curtis, British private engaged in a dispersal operation in Belfast. Curtis, a married 20-year-old, was the first British soldier to die on duty in Ireland since 1921. Another British soldier and two Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) officers were killed in February. On March 10th the Provos kidnapped and murdered three young off-duty soldiers in Ligoniel. In May, British sergeant Michael Willetts was killed by an IRA bomb planted in a Belfast police station. Willetts died while shielding four civilians from the blast. He was posthumously awarded the George Cross.

Attacks on British forces, some targeted and some incidental, continued through 1971. By August almost 100 people had been killed in politically motivated attacks, four times the number of the previous year. Catholic civilians had lost trust in the British Army due to its heavy-handed tactics in Ballymurphy, the Falls and elsewhere. This growing animosity handed the Provisional IRA new recruits and a civilian population willing to support and conceal them. Faulkner’s use of internment aimed to identify IRA leaders and volunteers and extract them from the general population. Faulkner hoped this would stem attacks on security forces and prevent a groundswell of IRA support that might trigger a full-scale civil war. As it turned out, internment had minimal impact on the capacity of Republican paramilitary groups. Many historians now consider it one of the most disastrous policy decisions of the entire Troubles.

Faulkner’s tough stand

The two men ultimately responsible for internment were Northern Ireland prime minister Brian Faulkner and British prime minister Edward Heath. Faulkner became prime minister in March 1971, following the resignation of James Chichester-Clark, himself worried out of office by escalating violence. A career politician and member of the Northern Ireland parliament for more than 20 years, Faulkner was a pragmatist but also a resolute Unionist. His first attempt to resolve the problems of 1971 was to offer mild political concessions, coupled with tough talk on security. Faulkner appointed a Catholic Unionist as his state minister, selected a non-Unionist in his cabinet and put opposition MPs in charge of important committees. Faulkner was no reformist, however, and these appointments were as far as he was likely to go. Faulkner also thundered publicly about the “thugs and murderers” in the IRA and promised his government would take tough action.

Faulkner claimed to be a reluctant convert to the idea of internment. He had witnessed its successful use to scatter and weaken the IRA in the late 1950s – but had opposed the idea under Chichester-Clark’s government. Nevertheless, by July 1971 Faulkner was actively lobbying for the internment of suspected Republican paramilitaries. Internment could not be implemented without the British Army and thus the backing of Westminster. When Faulkner and British leader Edward Heath discussed the issue in early August, Heath gave ‘in principle’ agreement to Faulkner’s request – but he wanted Faulkner to take action against radical Loyalists so that internment did not seem entirely focused on Catholics and Nationalists. Heath’s advisors suggested the internment of Loyalist paramilitary leaders, the seizure of weapons from Loyalist gun clubs and an indefinite ban on Loyalist parades and marches. Faulkner rejected all of these proposals, only agreeing to a six-month ban on parades. Thus was born a great folly: Faulkner’s one-sidedness and Heath’s unwillingness to impose conditions on internment meant that it became almost entirely focused on Northern Ireland’s Nationalist community.

Operation Demetrius

Internment itself commenced at dawn on August 9th, with raids carried out by the British Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) under the name Operation Demetrius. They were armed with lists of names compiled by RUC’s Special Branch and MI5, the British intelligence agency. These lists, It later emerged, were badly outdated. Many arrested during Operation Demetrius had been actively involved in the IRA for several years; some were civil rights campaigners who were not affiliated with paramilitaries at all. As per Faulkner’s instructions, Loyalist paramilitaries were not targeted. The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) had been bombing Catholic-owned stores in Belfast since early 1970, yet no member of the UVF was arrested and interned. The manner in which internment was instigated was itself a study in terror tactics. Houses were raided, mostly in the dead of night, catching the targets and their families asleep in their beds. Suspects were whisked away to police stations and prison camps, where they claimed of interrogation methods that bordered on torture. One internee, Patrick McClean, later described his arrest and transportation to Magilligan, a makeshift army camp in County Londonderry:

“I spent the first 48 hours period with the other detainees at Magilligan Camp. At the end of these initial 48 hours, a hood was pulled over my head and I was handcuffed and subjected to verbal and personal abuse, which included the threat of being dropped from a helicopter while it was in the air. I was then dragged out to the helicopter, being kicked and struck about the body with batons on the way. After what seemed about one hour in the helicopter I was thrown from it and kicked and batoned into what I took to be a lorry.”

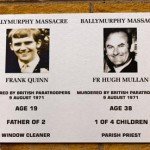

Operation Demetrius resulted in the location, arrest and internment of 342 people in three days. These sudden arrests triggered protests and violent riots in several Catholic areas across Northern Ireland. Some of the worst rioting broke out in Ballymurphy, a poor housing estate in Belfast’s west. Several hours into Demetrius, a squad of British paratroopers were sent into Ballymurphy to arrest suspected IRA volunteers. As they entered the estate the soldiers opened fire, later claiming they had come under attack from Republican snipers. Six civilians were shot dead in one day. Hugh Mullan, a Catholic priest, and 19-year-old Francis Quinn were both gunned down as they went to the aid of wounded people. Daniel Teggart was shot 14 times, most of these in the back. A further four civilians were killed by British forces over the next two days. Another man died from a heart attack after British soldiers terrorised him, putting an unloaded gun into his mouth and pulling the trigger. Eleven civilians died in what became known as the ‘Ballymurphy Massacre’. These killings paralleled the better known ‘Bloody Sunday’ shootings, perpetrated by the same regiment five months later.

At the end of August 1971, the British government convened an inquiry into allegations of brutality and torture during Operation Demetrius. The investigation, overseen by English parliamentary ombudsman Sir Edmund Compton, was poorly handled from the outset. Compton was a civil servant with no experience of conflict, policing or Northern Ireland. The inquiry’s hearings were conducted in camera with no public or press present. Witnesses were not allowed to be deposed or cross-examined. The inquiry heard testimony mainly from police, soldiers and civilian onlookers: only one of the 342 men arrested during Operation Demetrius appeared as a witness. The report concurred that internees had been treated with excessive physical exertion, placed in distorted and painful positions and bombarded with loud music – but Compton denied these measures constituted torture. “Where we have concluded that physical ill-treatment took place,” Compton wrote, “we are not making a finding of brutality… We consider that brutality is an inhuman or savage form of cruelty and that cruelty implies a disposition to inflict suffering, coupled with an indifference to or pleasure in the victim’s pain. We do not think that happened here.”

“The introduction of internment without trial in August 1971 ended what hopes remained that the Nationalists would cooperate with the Northern Irish government and, therefore, the prospects for some kind of power-sharing political accommodation that might undermine the IRA’s military campaign. Internment without trial, though welcomed widely in Britain at the time, was probably the single most disastrous measure introduced during the recent troubles, resulting in a major escalation of violence.”

Paul Dixon, historian

Many condemned the Compton Report as a whitewash. The report was debated on the floor of the British parliament, in the press and behind closed doors. Rights campaigners and lawyers pointed out that the treatment of internees was in breach of European Commission of Human Rights principles. Former World War II soldiers criticised the tactics used in Operation Demetrius, suggesting they would not have been permitted in prisoner-of-war camps due to the Geneva Convention. Conversely, Edward Heath was annoyed by the report because it did not absolve the Army from blame entirely. Heath was particularly outraged that evidence from civilians was given the same value as evidence from soldiers or the RUC. In a memo written in 1971 but found in 2005, Heath called Compton’s report “one of the most unbalanced, ill-judged reports I have ever read… They seem to have gone to endless lengths to show that anyone not given three-star hotel facilities suffered hardship and ill-treatment.”

In the end, the policy of internment failed to quash or minimise paramilitary violence. The great problem with internment was that it targeted Catholics and Nationalists but left Loyalist paramilitaries untouched. This one-sidedness hardened public disdain for British policy; the vast majority of Catholics were now convinced that the British military was little more than a tool for perpetuating Unionist discrimination. Incidents like the Ballymurphy Massacre, the brutal interrogation methods used by security forces and the Compton fiasco also created a sense of outrage that drove many Catholics into the welcoming arms of the IRA. The decision not to intern Loyalist paramilitaries was exposed as folly just weeks later when the UVF bombed McGurk’s Bar, killing 15 Catholic civilians. The use of internment and the jackboot fashion in which it was implemented also generated worldwide media attention, much of it critical of the British and Northern Ireland governments. Internment caused outrage in the United States, which had a large population of expatriate Irish, many of whom sympathised with the Nationalist cause. In cities with large Irish populations, such as Boston and Philadelphia, affluent Irish-Americans donated to local Nationalist clubs and societies; a good deal of this money found its way to the IRA and was used to acquire weapons and supplies. Internment was introduced to curtail paramilitary violence but instead provided it with both motive and means. It is no coincidence that 1972, the year immediately following internment, was the deadliest year of the Troubles.

1. Internment is the practice of arresting and detaining people without trial or due process. It is often used during periods of war or conflict, to remove dangerous individuals from civilian society.

2. Internment was introduced in Northern Ireland by prime minister Brian Faulker in August 1971. This was done with the reluctant backing of the British government.

3. A two-day military operation on August 9th and 10th 1971 (Operation Demetrius) rounded up and interned 342 suspected Republican paramilitary volunteers.

4. Faulkner’s use of internment proved controversial because no Loyalist paramilitary volunteers were interned, while numerous Republican internees complained of torture or brutalisation.

5. While internment was intended to curtail paramilitary violence, it further alienated and outraged Northern Ireland’s Catholics. Support for the Provisional IRA increased markedly after Operation Demetrius.

Patrick McClean recalls the brutality of internment (August 1971)

The Times: NICRA leads an anti-internment march in Belfast (January 1972)

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebekah Poole and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Poole and J. Llewellyn, “Internment in Northern Ireland”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/internment/