Alexander Antonov (1888-1922) was the main leader of the peasant uprising that broke out in the Tambov in the early 1920s. Antonov was an industrial worker who joined the Socialist-Revolutionary party during the rising political unrest in 1904. He is best known for leading the Tambov militia, or ‘Blue Army’, during its 1920-22 resistance to Bolshevik rule. He was eventually located and killed by the CHEKA.

Inessa Armand (1874-1920) was a French socialist who provided support to Lenin during his exile in Paris. She returned to Russia with him in April 1917 and became active in the new Soviet government, heading up the Zhenotdel women’s department. Letters between Armand and Lenin suggest a close personal relationship; some historians have speculated that the two were lovers and that Lenin, his wife Krupskaya and Armand lived in a virtual menage a troi. Armand’s death from cholera in 1920 deeply affected Lenin.

Nikolai Bukharin (1888-1938) was a Russian socialist and Bolshevik leader who played an important role in the new society. Born in Moscow to a family of school teachers, Bukharin became involved in left-wing political groups as a teenager, serving as a foundation member of the Komsomol (the Bolshevik youth league). By 1912 he was one of the party’s brightest one theorists, working – and occasionally disagreeing – with Lenin himself. Like Trotsky, Bukharin was exiled in New York at the time of the February Revolution, though he swiftly returned to Russia. Bukharin’s politics were more anarchistic and internationalist than those of Lenin: he opposed the signing of the Brest-Litovsk treaty, believing that a continuation of the war would incite socialist revolution in Germany. Bukhrain later lost faith in the international revolution and became an enthusiastic supporter of Lenin’s New Economic Policy. He joined the Politburo in 1924 and supported Stalin’s ascent to power, before falling out with the dictator over land collectivisation. Bukharin was eventually condemned for disloyalty and executed during Stalin’s purges in the mid-1930s.

Felix Dzerzhinsky (1877-1926) was a minor aristocrat of Polish birth who became a loyal Bolshevik and the party’s feared security boss. In his teens, Dzerzhinsky was expelled from school for involvement in radical political groups. He later joined Marxist parties in Lithuania and his native Poland, before travelling into Russia to support and work with revolutionaries there. Dzerzhinsky did not join the Bolsheviks until 1917 but his devotion to the revolution was spotted by Lenin. By July 1917 Dzerzhinsky was a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee; he later contributed to the planning of the October Revolution. But it is as chief of the fearsome CHEKA that Dzerzhinsky is best known. His attention to detail and his ruthlessness made Dzerzhinsky an ideal security head: he once famously described the mission of the CHEKA as “organised terror”. Dzerzhinsky headed the CHEKA for more than four years until its dissolution and replacement by the GPU in 1922. He remained in the upper echelons of the Soviet government, serving in ministerial roles until his death in mid-1926.

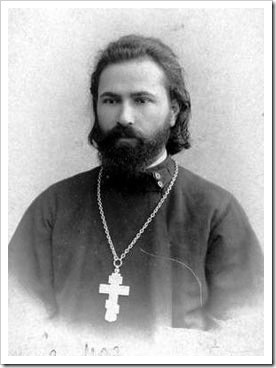

Georgy Gapon (1870-1906) was a Russian Orthodox priest and political agitator who contributed to political unrest in 1904-5. Gapon was born to an impoverished peasant family in Ukraine and in his teens received religious training. He later moved to St Petersburg where he worked as a teacher, organising charitable relief for the city’s poor, including industrial workers and their families. Gapon was recruited by the Okhrana to organise a zubatovshchina (state-run workers’ association) but it seems his real loyalties were with suffering workers. Charismatic and a compelling orator, by 1904 Gapon was organising factory workers into militant sections. In January 1905 he drafted a petition of workers’ demands for presentation to the tsar; this petition was being carried by protestors when they were gunned down by imperial troops on ‘Bloody Sunday’. Gapon later condemned the tsar’s response to this violence and openly called for revolution. He was hanged by SR agents in 1906 after they discovered his contacts with the Okhrana. (See also Bloody Sunday)

Adolf Joffe (1883-1927) was a communist revolutionary, diplomat and politician. Closely aligned with Trotsky, Joffe was involved in the Petrograd Soviet during 1905. He spent several years exiled in Siberia before returning in 1917 and eventually supporting the Bolsheviks. He later led the negotiating team at Brest-Litovsk, though the unpopularity of the treaty reduced his influence in the party. He committed suicide in 1927.

Lev Kamenev (1883-1936) was a long-serving Bolshevik revolutionary and, later, an important Soviet political leader. Kamenev was one of two Bolshevik leaders who opposed Lenin’s wish to seize power in October 1917. He later became chairman of the Moscow Soviet, a Politburo member and (with Grigory Zinoviev) was instrumental in the rise of Stalin. Kamenev was another victim of Stalin’s purges and show trials during the mid-1930s.

Fanya Kaplan (1890-1918) was a young Jewish woman who joined the Socialist-Revolutionaries in her teens. In 1906 she was sentenced to life imprisonment for involvement in terrorist acts, though she was later released. She is best known for her August 1918 attempt to assassinate Lenin, which led to her being dubbed ‘the Russian Charlotte Corday’. After shooting Lenin twice at a Moscow factory, Kaplan was arrested, tortured and executed. Despite suspicions to the contrary, it seems she acted alone rather than with the backing of the SRs or another group.

Alexander Kerensky (1881-1970) was a left-wing political leader who vied with Lenin for control of Russia during the tumultuous months of 1917. Ironically, Kerensky was born and raised in Simbirsk, also Lenin’s hometown; his father had been a teacher at Lenin’s school and later gave the future Bolshevik leader a written reference. Kerensky trained as a lawyer and provided advice to individuals who had been mistreated by the government. In 1912 he was elected to the fourth Duma as a member of the labour-aligned Trudovik party; he quickly took a lead role into investigations into the Lena River shootings that year. In March 1917 Kerensky was appointed Minister of Justice in the new Provisional Government, the only socialist in the cabinet. A series of government breakdowns enabled him to rise to War Minister (May) and then prime minister (July), largely because of his ambition and brilliant oratory. But Kerensky’s support for the war and his failed June Offensive in Galicia eroded his support and made him a target for more radical socialists. By September 1917 he had alienated those on the political Left and Right, while the Provisional Government commanded little support from either the people or the military. Kerensky fled the Winter Palace during the October Revolution, married an Australian woman and made his home in the United States, where he worked as an academic. (See also Alexander Kerensky)

Alexandra Kollontai (1872-1952) was arguably the leading female socialist revolutionary, particularly after 1917. Born into a Ukrainian military family, Kollontai married young but the marriage failed, in part because her true interest was in Marxist politics. She joined the SDs in 1899, worked with industrial labour groups and was a witness to the events of ‘Bloody Sunday’ in 1905. After the outbreak of World War I, Kollontai spent time in several European countries, where she attempted to convince socialist groups to oppose the war. She joined the Bolshevik movement in 1915 and supported Lenin’s call for revolution in October 1917. Kollontai is best known for leading Soviet social reform, particularly improvements to the rights and conditions of women. She served as Commissar for Social Welfare and helped set up the ‘women’s bureau’ Zhenotdel. In the early 1920s Kollontai supported the Workers’ Opposition faction, which criticised the party for allowing excessive bureaucracy and crippling decision-making by workers. She held no position of domestic influence thereafter but served as Soviet ambassador to Mexico and Sweden.

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1869-1939) was the wife of Vladimir Lenin and a notable Bolshevik revolutionary in her own right. Krupskaya was born in St Petersburg to a lower middle-class family that had previously boasted noble titles. She was a keen student with an interest in literature, history and politics. After completing her own education the young Krupskaya worked as a tutor while participating in political discussion groups during her spare time. She met Lenin in 1894 and they married four years later, during one of his periods in exile in Siberia. A member of the Social Democrats from the outset, she voted with Lenin at the 1903 party congress and thus became part of the Bolshevik faction. Krupskaya did not always agree with her husband, nor did she obediently yield to him. She later believed Lenin’s call for an October 1917 revolution was premature, though she came to accept it. After 1917 Krupskaya held high positions in both the Communist Party and the Soviet government, particularly in the fields of education (where she was deputy commissar) and the Soviet youth movement Komsomol.

Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) was the Bolshevik leader, the instigator of the October Revolution and, until his death, the dominant figure in the new society. He was born Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (‘Lenin’ was a revolutionary codename adopted later) in Simbirsk, his father a former peasant who had become a successful teacher. The Ulyanovs were politically aware and liberal minded, regularly discussing – and criticising – Russian government and society. In 1887 Lenin’s older brother, Aleksandr, was arrested and executed for involvement in an assassination plot against Tsar Alexander III. This had a profound effect on the young Lenin, who began studies in law while mixing with radical student political groups. By the mid-1890s Lenin had met his future wife, Krupskaya, and was involved in Marxist groups in St Petersburg. In 1895 Lenin was forced out of western Russia and into exile, where he would spend 18 of the next 22 years. He lived as a European nomad, spending time in London, Paris, Munich and Geneva and writing extensively about Marxism and contemporary political and economic systems. In 1902 Lenin published What is to Be Done?, a cry for better organisation and discipline in Marxist revolutionary groups. The following year he put these ideas into practice by forcing a split in the Social Democrats, Russia’s largest Marxist party. Lenin’s faction was dubbed the Bolsheviks (‘majority’). Lenin was soon forced back into foreign exile but the abdication of the tsar in 1917 allowed him to return to Russia. Arriving in April, he took command of the situation by issuing his April Theses, which demanded “Peace, Bread and Land” for the people, a boycott of the Provisional Government and socialist revolution at the earliest opportunity. From that point forward, the fate of the Russian Revolution – and indeed Russia – was shaped if not written by Lenin’s impatient and obsessive determination to craft a socialist state. (See also Vladimir Lenin)

Julius Martov (1873-1923) was an influential Russian Marxist who was the most prominent member of the Mensheviks. Born to a Jewish middle-class family, Martov became interested in left-wing politics as a student. His early years were spent working closely with Lenin; indeed the two were considered friends. He joined the SDs in 1900 and, with Lenin, founded the party newspaper Iskra. Martov and Lenin’s collaboration diminished following the 1903 party split. Martov became the de facto leader of the Mensheviks. He argued the party should agitate against bourgeois government but not directly attempt to overthrow it. Unlike right-wing elements in the Menshevik movement, he opposed World War I, along similar lines to Lenin. Martov is perhaps best known for walking out of the Soviet congress the day after the October Revolution. He returned to sit as a delegate in the short-lived Constituent Assembly but played no significant role in Russian politics thereafter.

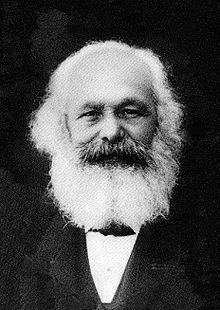

Karl Marx (1818-1883) was a German political philosopher whose writings provided the ideological impetus for a revolution in Russia. Born in Prussia to a middle-class Jewish family, Marx was trained and worked briefly as a lawyer – but his true interest was in political and economic theory, particularly the works of Georg Hegel. In 1844 Marx began a collaboration with Friedrich Engels that saw them undertake critiques of capitalist economies and societies in Europe. Their first major text was The Communist Manifesto, published in 1848, in which Marx and Engels argued that mankind was moving through a series of socio-economic phases, defined by ownership of capital and ‘class struggle’. Marx’s condemnation of capitalism and his theory of revolution became a guiding light for left-wing political movements across Europe – including the Russian Social Democrats and their factional offspring, the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks. Marx himself died in exile and in comparative poverty and was buried in London. (See also Marxism)

Pavel Milyukov (1859-1943) was the founder and leader of the Kadets and the first foreign minister in the Provisional Government. A historian and academic, Milyukov sat in the first State Duma, where he offered strong criticism of the government. He supported the tsarist government after the outbreak of war but by late 1916 was again condemning it. He is best known for his April 1917 telegram to the Allies, promising to keep Russia in the war until its completion. The public backlash forced his resignation from the Provisional Government. After October 1917 he fled to France, where he lived out his days in exile.

Georgi Plekhanov (1856-1918) was a Marxist revolutionary and a founding member of the Social Democrats (SDs). Though he voted with Lenin at the 1903 SD congress, Plekhanov later opposed the Bolsheviks on many issues. He supported the war effort, argued that the February Revolution was premature and disrupted, and dismissed Lenin as a German agent. Plekhanov was forced to flee Russia in 1918.

Fyodor Raskolnikov (1892-1939) was a socialist naval officer stationed at Kronstadt. A member of the Bolsheviks, Raskolnikov twice led the Kronstadt sailors into Petrograd with the intent of providing military support to a Bolshevik revolution. He later served as a diplomat for the Soviet Union, before being murdered by Stalinist agents.

Mikhail Rodzianko (1859-1924) was a former tsarist military officer who later became a liberal-conservative politician. Rodzianko entered the third Duma in 1907; four years later he was elected as its chairman. In late 1916 and 1917, he sent Nicholas II a series of telegrams warning of the escalating tensions in Petrograd; most were ignored. Rodzianko then led the negotiations that resulted in the tsar’s abdication. He later fled Russia to Serbia, where he died three days after Lenin.

Alexander Shlyapnikov (1885-1937) was the most prominent spokesperson for the Workers’ Opposition, the anti-statist Bolshevik faction that emerged in 1920. Closely linked to industrial workers and their unions, Shlyapnikov served as Minister for Labour in 1918. Over time he became critical of the Soviet regime’s centralised control of labour, adopting a syndicalist line. Shlyapnikov was excluded from positions of influence and later executed during the Stalinist purges.

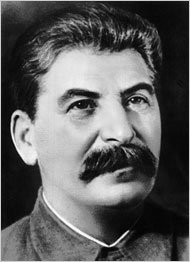

Joseph Stalin (1879-1953) would become known as the ruthless dictator who dominated Russia from the late 1920s to his death in 1953 – but Stalin’s role in the Russian Revolution was comparatively minor. Born Ioseb Dzhugashvili to a poor family in Georgia, Stalin began training for the priesthood but was expelled from the seminary before graduating. He became a Marxist and joined Lenin’s Bolshevik faction in 1903. Stalin’s early contribution to Bolshevism was largely practical: he raised funds for the movement by extortion or robbing banks; at other times he was involved in the production and dissemination of propaganda. This naturally made him a wanted man: Stalin spent much of the decade before 1917 either in prison or in exile. After the abdication of the tsar, Stalin returned to Petrograd and muscled his way into the editorship of Pravda; in his first editorials, he pledged to support the Provisional Government. After April, Stalin fell in behind Lenin, supporting the overthrow of the government. Through 1917 he continued in charge of Pravda, while managing Lenin’s personal security. During the Civil War Stalin served in the Politburo, Sovnarkom and as Commissar for Nationalities, a portfolio that gave him responsibility for non-Russians in the old empire. In 1922 he was appointed General Secretary of the Communist Party, a position he used to expand his support in the party hierarchy, allowing him to seize power after the death of Lenin.

Yakov Sverdelov (1885-1919) was a talented young Bolshevik leader who worked closely alongside Lenin in 1917 and with the Soviet government during the first months of its rule. He also served as chairman of the Congress of Soviets Central Executive Committee. Trotsky described him as a “superb organiser”, while many considered him to be Lenin’s natural successor as leader of the Soviet Union. Sverdelov died in uncertain circumstances in 1919, probably of influenza.

Leon Trotsky (1879-1940) was a leading socialist writer, thinker and organiser, the second-most influential revolutionary after Lenin. Born Lev Bronstein to a Jewish-Ukrainian family, Trotsky became involved in Marxist groups while a student. He attended the 1903 Social Democratic party congress, where he sided with Julius Martov and the Mensheviks, but he later attempted to reconcile and reunite the party’s divided factions. Trotsky made important contributions to the 1905 Revolution, particularly in the formation and organisation of the St Petersburg Soviet. He was later arrested and forced into exile, before escaping abroad. Trotsky returned to Russia in 1917 and over the course of the year began to align with Lenin and the Bolsheviks. In October he oversaw the operations of the Military Revolutionary Committee and the Red Guards; the Bolshevik revolution later that month succeeded largely because of Trotsky’s planning. In the new society, he served as Commissar for War, playing critical roles in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the emergent Red Army and the Civil War. Trotsky was viewed as the natural successor to Lenin – but he also alienated several individuals in the Bolshevik party, which allowed Stalin to undermine and replace him after Lenin’s death. Trotsky went into exile and wrote extensively about the revolution and left-wing politics in general before he was murdered by a Stalinist agent in Mexico. (See also Leon Trotsky)

Grigory Zinoviev (1883-1936) was a foundation member of the Bolsheviks and participated in party decision-making at the highest levels. Zinoviev returned to Russia with Lenin in April 1917 but opposed Lenin’s push for an armed revolution in October that year. He later served as a commissar, a Politburo member and director of the Comintern. After Lenin’s death, Zinoviev sided with Stalin against Trotsky, allowing Stalin to seize control of the party. Zinoviev was later tried and executed on Stalin’s orders.

© Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Russian Revolution who’s who – revolutionaries” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/russian-revolution-whos-who-revolutionaries/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].