Bloody Sunday 1905 began as a relatively peaceful protest by disgruntled steel workers in St Petersburg. Angered by poor working conditions, an economic slump and the ongoing war with Japan, thousands marched on the Winter Palace to plead with Tsar Nicholas II for reform. But the tsar was not present and the workers were instead gunned down on the streets by panicky soldiers. At another time in Russian history, the mass killing of dissident civilians might have frightened the rest of the population into silent obedience – but the authority of the tsarist regime had been diminishing for months. Popular respect and affection for the tsar, already in decline prior, took a sudden turn for the worse. ‘Bloody Sunday’ triggered a wave of general strikes, peasant unrest, assassinations and political mobilisation that became known as the 1905 Revolution.

Industrial workers also laboured under appalling conditions. The average working day was 10.5 hours, six days a week, but 15-hour days were not unknown. There were no annual holidays, sick leave or superannuation. Workplace hygiene and safety were poor; illness, accidents and injuries were common-place and with no leave or compensation available, sick or injured workers were summarily dismissed. Factory owners often imposed arbitrary fines for lateness, failing to meet production quotas or more trivial ‘offences’ like toilet breaks and talking or singing while working. Most workers lived in crowded tenements or ramshackle sheds owned by their employers; this accommodation was poorly constructed, overcrowded and lacked adequate heating, water or sewage facilities.

The dissatisfaction of factory workers grew steadily but became particularly acute in the final months of 1904. Not only had Russia entered its difficult and ultimately disastrous war with Japan, its national economy slipped into a severe recession. Production, foreign trade and government revenue all declined, compelling companies to dismiss thousands of workers and increase pressure on those they retained. There were significant increases in homelessness, poverty and family; the tsarist government’s only response was to ask zemstvo leaders to organise charitable relief. Food prices in the cities increased by as much as 50 per cent, however wages failed to increase correspondingly.

The deteriorating conditions naturally generated unrest and dissent. Some of this came from liberals, who renewed demands for an elected constituent assembly. Industrial workers also formed so-called ‘workers’ sections’, which served as militant discussion groups and, later, strike committees. Several of these sections were led by Georgy Gapon, a Ukrainian-born priest who had previously received support from the Okhrana (tsarist secret police).

Gapon was an articulate and convincing public speaker and a skilled activist – but he was no obedient tool of the government. Working closely with impoverished and suffering workers, his loyalties eventually shifted to them. In late 1904 Gapon became an instrumental figure in unrest at the Putilov steel plant in St Petersburg. When factory managers sacked four workers there, the workers’ sections responded angrily and began organising strikes and demands for improvements to their rights and conditions. Somov, a Menshevik organiser, later commented on the tone of these meetings:

I found myself at several meetings [of Gapon’s workers’ sections] whose characteristic feature was that they imbued all demands with a ‘search for justice’, a general aspiration to put an end to the present impossible conditions… And although I thought that in all of these demands, workers were motivated not so much by considerations of a material character, as by purely moral aspirations to settling everything ‘according to justice’ and to force employers to atone for their past sins.

“The revulsion following the slaughter soon engulfed the whole nation and there were wide-spread manifestations of popular grief, indignation and anger against the guilty tsar. Not just the industrial workers but the middle classes, intellectuals, professional organisations and the whole of Russian society were roused to fury. The tsar, typically, did nothing until the February assassination of his uncle finally impelled him to issue a decree authorising the election of a consultative assembly. The announcement was sadly inadequate to respond to the popular mood and only served to spur both liberals and revolutionaries…”

Alan Wood, historian

As several thousand workers approached the Winter Palace, officers called out the palace’s security garrison to guard its entry points. As the workers approached the soldiers opened fire on the crowd. It is not known whether an order was given or whether soldiers fired spontaneously or in response to aggression. The number of victims is also unclear: government sources declared that 96 were killed, eyewitnesses suggested in excess of 200, while reports and propaganda from revolutionary groups claimed even higher figures.

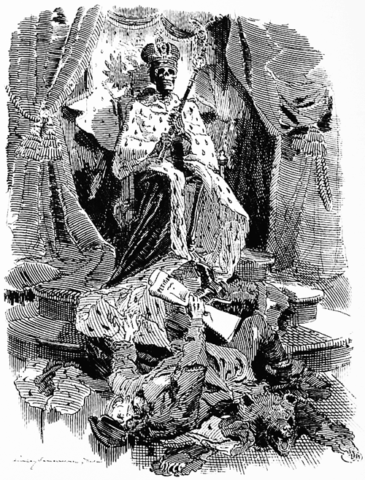

The events of ‘Bloody Sunday’ reverberated around the world. In the newspapers of London, Paris and New York, Nicholas II was condemned as a murderous tyrant. Within Russia, the response was also strong. Once the empire’s ‘Holy Father’, the tsar was given the epithet ‘Bloody Nicholas’. Marxist leader Peter Struve dubbed him the ‘People’s Executioner’. An infuriated Gapon, who escaped the violence of January 9th, declared that “There is no God any longer. There is no tsar!” The day after the killings, around 150,000 in the capital showed their disgust by refusing to work.

Over the coming days, the strikes expanded around St Petersburg and other cities in the empire, including Moscow, Odessa, Warsaw and the Baltic states. Later, these actions became more coordinated and were accompanied by demands for political reform. Over the course of 1905, tsarism faced its most dire challenge in its three-century history.

1. Russian industrial workers endured low wages, poor working conditions and appalling treatment from employers.

2. Conditions worsened in 1904 due to the war and economic recession, leading to the formation of workers’ sections.

3. In January 1905 workers at the Putilov plant, led by Georgy Gapon, drafted a petition intended for the tsar.

4. When they attempted to deliver this, scores of workers were gunned down in the street by tsarist soldiers.

5. ‘Bloody Sunday’, as it became known, eroded respect for tsarism and contributed to a wave of general strikes, political demands and violence that became the 1905 Revolution.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Bloody Sunday 1905” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/bloody-sunday-1905/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].