In October 1949, Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) claimed control of China and declared the formation of a new republic. China was not easily conquered, however, and not everyone welcomed its new rulers. The new regime faced plenty of opposition from several different corners: defeated Nationalist soldiers, former backers of the Guomindang, landlords and capitalist businessmen, political moderates and democrats, warlords and provincial leaders, ethnic minorities, Christians and foreigners. For Mao and the CCP, the 1950s became a critical decade for identifying and suppressing opposition and resistance. It began with ‘Speaking Bitterness‘ against rural landlords and ended with Mao’s attacks against critics and dissenters at the Lushan plenum in 1959. In between, the communists launched several campaigns to suppress their perceived enemies.

The significant action was the Suppression of Counter-Revolutionaries campaign (or zhen fan). It was launched in March 1950, six months after the formation of the People’s Republic. As the name suggests, this campaign sought to identify and wipe out remaining opposition to the CCP, including remnants of the Nationalist army and supporters of the Guomindang. The suppression campaign was focused mainly on southern and eastern cities, where citizens had little experience of the communists and no reason to support them. The campaign began with the introduction of martial law in Chongqing, Sichuan province. Chongqing had served as Jiang Jieshi’s capital during World War II. Because of this it housed many former Nationalists, soldiers and officials. By the end of 1949 some of them had formed an insurgency and were attempting to sabotage CCP control of Chongqing by encouraging strikes and lawlessness. Party commanders in the city responded by seizing weapons, jailing 7,400 former Nationalists and executing 361 insurgents. By the end of 1950 order had been restored in Chonqqing.

Drawing on the successes in Chongqing, Mao Zedong ordered the suppression campaign be extended to other cities. Mao urged CCP cadres to be less brutal than in Chongqing; he believed the skills and cooperation of industrialists, business owners and the urban middle classes were still needed. Rather than using coercion, Mao bombarded the cities with propaganda, urging their citizens to reject counter-revolutionary groups and ideas. Former Nationalists were demonised, depicted as ghoulish, fedora-wearing conmen, eager to steal and exploit. The CCP government also banned dozens of political, religious and semi-religious organisations, including the Guomindang, Christian churches, Buddhist temples, Shanghai’s Green Gang and folk religions like Tongshanshe and Yiguandao. The leaders of these groups were exiled, imprisoned or executed. The government also formed the People’s Tribunals in July 1950. Though ostensibly created to assist with land reform, the Tribunals also had the authority to deal with “despots, native bandits, special agents, counter-revolutionaries and criminals”, as well as those who “plot sabotage activities and undermine social security”.

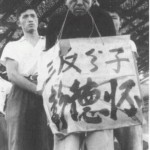

After its relatively lukewarm start, the Suppression of Counter-revolutionaries campaign escalated quickly at the end of 1951. This escalation was driven by CCP cadres, government propaganda and popular action. One of the features of the Suppression campaign in 1951 were huge mass meetings, held in public spaces or stadiums and attended by thousands of people. These meetings were urban versions of ‘Speak Bitterness’, though they tended to be deadlier for those who stood accused. Suspects were paraded, accused of counter-revolutionary activities or sympathies, intimidated into self criticism then subject to humiliation, beatings or execution. At some mass meetings more than 200 people were shot. According to Mao, 700,000 “class enemies” were executed during the Suppression campaign. Some historians consider this an underestimation. According to human rights activist Zhou Jingwen, around half a million people committed suicide, driven by shame, humiliation or coercion. More than one million people were also imprisoned or held in forced labour camps. The Suppression of Counter-revolutionaries campaign was slowed in 1952 and eventually halted in July 1953.

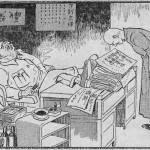

As well as eliminating external threats, the CCP also moved against problems inside the party. In autumn 1951 party leader Gao Gang launched a campaign against ‘bureaucratism’ in the northern province of Manchuria. Gao alleged that many CCP cadres were heavily involved in corruption, embezzlement and graft, so were stealing large amounts of money from the state. Gao filed a report with Mao Zedong, who later blamed this internal corruption on the “sugar coated bullets” of the bourgeoisie. In November 1951 Mao formally launched the Three Antis campaign (san fan). Its purpose was to eradicate three specific ‘evils’: corruption, waste and bureaucracy. Its main targets were members of the CCP, particularly urban officials who had direct contact with financial and business interests, and so were susceptible to corruption. “Cleanse away the filth and poison left over in our country from the old society”, Mao urged his followers. Cadres were encouraged to identify and criticise CCP officials who had taken bribes, shown leniency or favouritism towards business interests, or were deriving excessive benefit from their position. Corrupt party members were dubbed “tigers” and the groups who sought them were “tiger-hunting teams”.

The Three Antis came to an end in October 1952 but not before it had claimed some prominent victims. In November 1951 Liu Qingshan and Zhang Zishan, high ranking CCP secretaries in the northern prefecture of Tianjin, were arrested with Mao’s approval. Liu and Zhang were accused of embezzling state funds (the amounts reported vary between 1.7 million and 1.5 billion yuan) that was set aside for flood mitigation, ship building and the construction of an airport. They were also accused of conspiring with wealthy businessmen to inflate the cost of state contracts. In addition, Liu and Zhang were indicted for living an extravagant bourgeois lifestyle, rather than lives of communist austerity. The strength of the case against them was uncertain, nevertheless they were found guilty and executed in February 1952. Their treatment was held up as an example to other party members who stole from the state or took bribes and backhanders.

“The campaigns created an unprecedented political storm against the bourgeoisie. Under extreme political heat, entrepreneurs moved quickly, if reluctantly, to comply. Noncompliance meant humiliation, trial and even betrayal by their own families. Most private entrepreneurs were found guilty, one way or another. The timing of the Three and Five Antis campaigns revealed the growing impatience of the new regime…”

Xiaobing Li

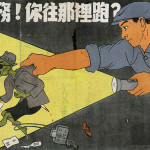

A second campaign, the Five Antis (or wu fan), was launched in early 1952, almost concurrently with san fan. The five ‘evils’ nominated by Mao were bribery, tax evasion, theft of state property, cheating on government contracts and stealing economic information. This time, the targets were businessmen and capitalists. Corruption, Mao argued, was a product of capitalism and the greed it nurtured, so the answer was to target capitalists. Many corrupt capitalists had already been identified during the Three Antis (the two campaigns were closely connected). Five Antis cadres sought the help of ordinary people, enlisting thousands of spies and informants to monitor suspect individuals and businesses. State rhetoric and propaganda encouraged clerks and workers to inform the government of suspicious activity.

The Five Antis campaign had a profound effect on Chinese business. The campaign’s culture of secret denunciations saw many business owners falsely accused, by rivals or cadres. By 1953 around 450,000 private businesses had been charged with one of the ‘five evils’; around 340,000 were found guilty. Thousands more were intimidated or terrorised into liquidating their business or surrendering it to the state. Some were dragged to public meetings and subjected to accusations and humiliation, before being fined and having their businesses seized. Many committed suicide after losing their property and livelihood. The Five Antis not only enriched the coffers of the government, it contributed to an intensifying climate of fear, particularly among capitalists and small businessmen. According to a reporter in Hong Kong in 1951, “those who come out of communist China with an astonishing unanimity refer to… this constant haunting fear… The arms of the party are far reaching. They extend… to each individual and affect the words and thoughts of all.”

1. When Mao Zedong and the CCP seized control of China in October 1949 they faced considerable opposition and resistance from former Nationalists and others.

2. The CCP’s first response was the Suppression of Counter-revolutionaries campaign, launched in 1950, which sought to identify and eliminate opposition, particularly in the cities.

3. Launched in 1951, the Three Antis campaign targeted corruption, waste and ‘bureaucratism’ among party officials. It was followed by the Five Antis campaign in early 1952, which targeted corrupt capitalists and businessmen.

4. These campaigns were driven by government propaganda, CCP cadres and urban mass meetings, where suspected persons were subject o self criticism, accusation and humiliation.

5. The death toll from these campaigns is unknown but is probably close to one million people. Together these campaigns generated a climate of fear, forcing those who disagreed with CCP policies into compliance and obedience.

© Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Glenn Kucha and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

G. Kucha & J. Llewellyn, “The Three-Antis and Five-Antis”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/three-antis-five-antis/.

This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.