In its first years, the United States military intervention in Vietnam enjoyed strong levels of public support. This was largely the product of Cold War paranoia and Domino Theory propaganda: Americans feared communist expansion and aggression and were prepared to back strong action. Americans were also supportive of South Vietnamese sovereignty and independence. They were outraged by reports of Viet Cong terrorist attacks and inflamed by reports of attacks on US naval ships in the Gulf of Tonkin (August 1964). By 1967 most Americans remained committed to Vietnam, though dissatisfaction with president Lyndon Johnson’s handling of the war had been rising since late 1965. If there was one event that caused a shift in public opinion it was the Tet Offensive of January 1968. The Tet Offensive humiliated the White House by thwarting its hopeful assessments that the war was being won. By March 1968, public satisfaction with Johnson’s overall presidency was at an all-time low. This, along with division and opposition within Johnson’s Democratic party, contributed to his decision not to seek re-election.

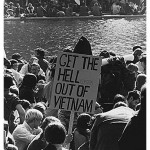

The years 1967-69 produced a gradual but steady growth in anti-war movements. Organisations opposing the war had been around since the early 1960s but their membership was mostly limited to university students, radical political groups and some churches. Around 25,000 people marched against the war in Washington in April 1965. Similar numbers attended a protest in New York City in March 1966. There were comparable protests in dozens of cities around the world, including London, Paris, Rome and Melbourne. By 1967 the anti-war movement had been joined by some high-profile figures, including celebrities and intellectuals. In March 1967 almost 6,800 academics and teachers put their signature to a three-page advertisement in the New York Times, condemning the war and calling for an immediate American withdrawal from Vietnam. Some of the other notable figures to publicly speak out against the war included:

Philosophers Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Satre, who claimed that the US had breached international and human rights law with regard to Vietnam. In 1967, Russell and Satre organised and convened a hypothetical ‘war crimes tribunal’ in Sweden, in which American policy and alleged war crimes in Vietnam were ‘put on trial’. The US government ignored these proceedings.

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King, who had been a vocal critic of the war since 1965. King argued that American involvement in Vietnam was an act of neo-colonialism and that the billions being channelled into the war would be better spent on social services for ordinary Americans. In April 1967, King delivered a speech titled “Beyond Vietnam”, calling for a spiritual and moral questioning of America’s foreign and domestic policy.

Heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali (born Cassius Clay) was also an outspoken critic of the Vietnam War. Ali had recently converted to Islam, declared himself a conscientious objector and refused military service. He did so with characteristic outspokenness, announcing that he was “not going 10,000 miles to help murder, kill, and burn other people to simply help continue the domination of white slavemasters over dark people the world over”. Ali’s refusal to be drafted led to a criminal conviction and five-year prison sentence, though this was later overturned by the US Supreme Court.

Numerous academics, intellectuals, writers, actors and musicians also criticised the war, both in their public statements and in their art. Among these vocal critics of the Vietnam War were Joan Baez, Noam Chomsky, Judy Collins, Bob Dylan, John Fogerty, Jane Fonda, Allen Ginsberg, Charlton Heston, Albert Kahn, Norman Mailer, Joni Mitchell, Carl Sagan, Susan Sontag, Benjamin Spock, Donald Sutherland and Howard Zinn.

Another notable factor in rising opposition to the Vietnam War was a shift in media coverage. Until mid-1967 American reporting on the war ranged from neutral to favourable for the government. The Vietnam War was portrayed as a just cause, waged against the malevolent and destructive forces of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong. Much of this information came from press correspondents and camera crews in South Vietnam, some of whom accompanied American troops on combat operations. But US military commanders implemented strict controls on reporting: they regulated where Western journalists could go, who they could speak to and what information they were given. Reporters in Vietnam came to refer to daily briefings as “the five-o’clock follies”, since they contained nothing of substance other than successful battle reports and optimistic stories.

By the summer of 1967, the Vietnam War was dominating news reports, taking up three quarters of television bulletins and several pages in daily newspapers. The tone of these reports was changing noticeably. Reports and editorials displayed growing scepticism about the government’s predictions of victory – even pessimism about whether victory was even possible. The Johnson administration briefly recalled General William Westmoreland from Vietnam to update the media, while Johnson’s national security advisor, Walt Rostow, declared that he could “see light at the end of the tunnel”. Yet combat deaths continued to increase and by Christmas 1967 more than 16,000 Americans had been killed in Vietnam. The Tet Offensive (January 1968) humiliated the government and boosted the ranks of the anti-war movement. Once been filled with students, left-wing radicals and peaceniks, anti-war groups now attracted large numbers of ordinary Americans: workers, housewives, policemen, high school students, even some politicians. The trusted CBS newsreader Walter Cronkite seemed to speak for many Americans when he said after the Tet Offensive:

“To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past. To suggest we are on the edge of defeat is to yield to unreasonable pessimism. To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion. On the off chance that military and political analysts are right, in the next few months we must test the enemy’s intentions, in case this is indeed his last big gasp before negotiations. But it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honourable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy – and did the best they could.”

“Although never able to create enough pressure on decision-makers to end US involvement in the war, the anti-war movement served as a major constraint on their abilities to escalate. The movement played a significant role not only in Lyndon Johnson’s 1968 decision not to seek another term but also in the Watergate affair that brought down President Richard Nixon. In many ways, the movement’s greatest importance was its legacy… For a quarter of a century after the end of the war, American presidents worried about creating another powerful anti-war movement that would oppose the interventions they contemplated.”

Melvin Small

The anti-war movement reached its peak in late 1969. On November 12th Associated Press journalist Seymour Hersh broke the story of the My Lai massacre, an incident concealed by the US government and military for 18 months. Three days later, around two million Americans joined in a national day of protest. It was by far the largest organised protest in American history. Across the country, civilians strung up banners, wore black armbands, held candlelight vigils, said prayers and chanted the names of dead soldiers. This protest was most concentrated in Washington, where more than 400,000 people gathered. They lingered on the steps of the Capitol building, outside the White House and other Washington landmarks, listening to prominent speakers and musicians such as Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie and Peter Paul and Mary. President Richard Nixon’s response was to remain in the White House and declare that he was “not affected” by the protest. General Earle Wheeler, the country’s highest-ranking military officer, dismissed the protestors as “interminably vocal youngsters, strangers alike to soap and reason”.

The anti-war movement would never again command these numbers – but it was reignited in May 1970 after news broke that US and ARVN troops had invaded Cambodia. Rather than its promised winding down and ‘Vietnamisation’ of the war, the Nixon administration was expanding it across borders into other nations. This fuelled an explosion of protest around the country, some of the most radical taking place on university campuses. At Kent State University in Ohio, students protested and rioted for four days, damaging property and setting fire to a building used to train military reservists. The Ohio governor responded by calling in the state’s National Guard. On May 4th these Guardsmen confronted 2,000 protesting students in a car park and around two dozen troops began firing weapons. Four students were killed, another was struck in the spine and paralysed, while a further eight were wounded. A Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph taken at the scene shows a distraught female protestor with one of the dead victims. The Kent State shootings provided stark and troubling images. To many Americans they were evidence of a government out of control, a government more willing to shoot its own citizens than withdraw from a disastrous foreign war.

The Kent State University shootings caused a resurgence in anti-war protests around the country. Many colleges closed in protest: students went on strike and professors refused to teach. Demonstrations became more radical, confrontational and violent. Meanwhile, support for the war continued to plummet in opinion polls. A May 1971 Gallup poll suggested 61 per cent of Americans now thought that US involvement in the war was wrong. The Nixon administration could not afford another scandal, yet another soon followed. In June the New York Times began publishing excerpts from a 7,000 page Department of Defense document. The ‘Pentagon Papers’, as they became known, were leaked to the press by Daniel Ellsberg, a former advisor to Robert McNamara. They contained a thorough history of America’s political and military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1968, along with relevant memoranda, briefings, diplomatic cables and other official communiques.

Analysis of the Pentagon Papers confirmed what the anti-war movement had long said about US involvement in Vietnam. Washington did not have precise war aims and its military strategy was inconsistent and often ineffective. US intelligence on Vietnam had been fatally wrong at several points. The government had not always informed the public of military and political developments in Vietnam, and in some cases, information was deliberately misrepresented or concealed from the press and the people. The Pentagon Papers called America’s involvement in Vietnam into question. It was also a searing indictment on how four different presidents had handled the Vietnam issue. Nixon, whose administration began a year after the Pentagon Papers were compiled, was largely immune from these criticisms. He was outraged nevertheless, concerned that the Pentagon Papers would undermine America’s mission in Vietnam. Nixon ordered White House lawyers to suppress further publication of the papers, a move that the Supreme Court ultimately decided was unconstitutional. When Nixon’s attempt at legal suppression failed, the CIA went in search of incriminating information about Ellsberg, breaking into the office of his psychiatrist.

1. In the first years of US military involvement in Vietnam, public support for the war remained high. Most Americans, driven by Cold War concerns, were in favour of halting communist expansion in Asia.

2. The Tet Offensive shattered the prospects of a rapid victory in Vietnam. It produced a downswing in support, the withdrawal of Lyndon Johnson from reelection and the growth of the anti-war movement.

3. The anti-war movement began mainly in universities in the mid-1960s. It reached its peak in 1967-69 with the involvement of high profile figures, several major demonstrations and shifting media attitudes.

4. The November 1969 moratorium against the Vietnam War and the 1970 shooting of four protesting students at Kent State University Ohio both galvanised and radicalised the anti-war movement.

5. The publication of the Pentagon Papers in mid-1971 further contributed to anti-war sentiment and heightened distrust of the government and its pronunciations about the war.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The anti-war movement”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/anti-war-movement/.