The Gulf of Tonkin incident (August 1964) provided a trigger for greater American involvement in Vietnam. At the centre of this incident was the USS Maddox, one of several American naval vessels patrolling the sea east of North Vietnam. The USS Maddox was an armed destroyer – but she was also outfitted to gather intelligence by monitoring North Vietnamese radio transmissions, radar and defence systems. This information was relayed to the Pentagon and used to organise covert attacks against North Vietnam. These attacks, codenamed Operation 34A, were planned and organised by the CIA and carried out mainly by South Vietnamese commandos, using unmarked Norwegian boats. The last week of July 1964 produced a significant escalation in these attacks. A brigade of South Vietnamese commandos was parachuted into North Vietnam, probably to operate undercover there, but was quickly captured. Planes provided by the CIA were used to bomb North Vietnamese border posts. On July 31st, a joint operation involving South Vietnamese and US Special Forces attacked two islands off the coast of North Vietnam.

Hanoi decided to respond to these hostile attacks on North Vietnam. At noon on August 2nd three North Vietnamese torpedo boats approached and fired on the USS Maddox. All torpedoes missed their target. The attackers were driven back by gunfire from the Maddox, which also called in air support from a nearby carrier. One of the torpedo boats was reportedly sunk; the other two sustained damage and limped back to base. Two days later the Maddox and another American ship, the USS Turner Joy, claimed to have responded to another North Vietnamese torpedo attack. US president Lyndon Johnson informed the American public of these attacks two days later. Speaking with measured anger, Johnson promised an immediate but proportionate response:

“This new act of aggression, aimed directly at our own forces, brings home to all of us the importance of the struggle for peace and security in south-east Asia. Aggression by terror against the peaceful villagers of South Vietnam has now been joined by open aggression on the high seas against the United States of America. The determination of all Americans to carry out our full commitment to the people and to the government of South Vietnam will be redoubled by this outrage. Yet our response, for the present, will be limited and fitting. We Americans know, although others appear to forget, the risks of spreading conflict. We still seek no wider war … It is a solemn responsibility to have to order even limited military action by forces whose overall strength is as vast and as awesome as [ours], but it is my considered conviction that firmness in the right is indispensable today for peace.”

Johnson also promised to seek a resolution from Congress, authorising him to “take all necessary measures in support of freedom and in defence of peace in south-east Asia.” On August 5th, the day after addressing the nation, Johnson ordered a small but precise series of bombing runs. Codenamed Operation Pierce Arrow, this mission saw American planes fly 64 sorties to bomb major torpedo boat bases along North Vietnam’s coastline. The same day, Johnson wrote to members of Congress asking them to endorse “all necessary action to protect our armed forces and to assist nations covered by the SEATO Treaty”. Congress duly considered Johnson’s request. The resolution motion encountered little dissent or opposition, both in the House of Representatives and the Senate. On August 10th, a week after the attack on the USS Maddox, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (officially titled Asia Resolution 88-408), which read in part:

“Naval units of the Communist regime in Vietnam, in violation of the principles of the Charter of the United Nations and of international law, have deliberately and repeatedly attacked United States naval vessels lawfully present in international waters, and have thereby created a serious threat to international peace … These attacks are part of a deliberate and systematic campaign of aggression that the Communist regime in North Vietnam has been waging against its neighbours … The Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression. The United States is therefore prepared, as the President determines, to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force, to assist any member or protocol state of the Southeast Asia Collective Defence Treaty requesting assistance in defence of its freedom.”

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution gave Johnson a temporary respite from unpleasant choices in Vietnam… Having stood up to communist aggression, Johnson now sounded a moderate note. In speeches during the campaign, he emphasised giving Vietnam limited help: He would “not permit the independent nations of the East to be swallowed up by Communist conquest” – but it would not mean sending ‘American boys 10,000 miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves’.”

Robert Dallek, historian

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution had legal and political implications. According to the United States Constitution, the president is commander-in-chief of the armed forces and may deploy them as he sees fit. The president does not have the power to declare war, however; this power is exclusively reserved for Congress. The wording of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution bypassed these obligations. Johnson was empowered to use military force in south-east Asia, with congressional backing, yet without a formal declaration of war against North Vietnam. The unfolding conflict in Vietnam lasted ten years but remained an undeclared war; it has variously been described as a “multinational intervention” or a “police action”. Significantly for Johnson, Congress’ endorsement of the resolution was overwhelming. The House of Representatives passed it unanimously 416-0, the Senate 48-2. This gave the hitherto cautious Johnson a confidence boost – and something of a congressional blank cheque – to proceed with military action in Vietnam.

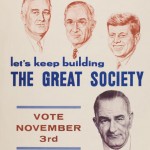

Despite this broad support, Johnson took no decisive action until after the presidential election of November 1964. His opponent, Republican nominee Barry Goldwater, was a staunch conservative and even more of a ‘hawk’ than Johnson. Goldwater criticised the incumbent president for being “soft on communism” and promised more aggressive tactics against insurgents and communist regimes in Asia. This played into the hands of Johnson’s campaign team, who painted their candidate as a peace-seeking moderate who was reluctant to commit American troops to war but would do so if necessary. Goldwater, they suggested, was a warmonger who would resort to using nuclear weapons. Goldwater’s campaign slogan was “In your heart, you know he’s right”; Johnson’s team responded with “In your guts, you know he’s nuts”. In November 1964 Johnson recorded one of the most decisive election wins in US history, winning 61.1 per cent of the popular vote and 44 of the 50 states. The 1964 election also gave Johnson’s Democratic Party a majority in both houses of Congress. Johnson now had a legislative mandate for his Great Society reforms – and a full four-year term to deal with communists in south-east Asia.

After his inauguration (January 1965) Johnson’s attention returned to military strategy in Vietnam. By early March, American troops were being landed at Da Nang’s ‘China Beach’. American combat troops were initially tasked in defensive roles, deployed in South Vietnamese enclaves at the greatest risk of Viet Cong attack. The early rules of engagement for US troops required them to occupy and defend “critical terrain features”, rather than engaging in “day to day activities against the Viet Cong”. Military commanders, however, were unsatisfied with this defensive approach. The only effective strategy, they believed, was to launch offensives to eliminate Viet Cong troops and bases. Over time these terms of engagement were revised and relaxed, allowing US troops to move outside their defined areas and to seek out the enemy. As American-held territory and positions were expanded, US troop numbers were gradually but inevitably increased. In March 1965 there were an estimated 17,000 US ground troops in Vietnam. By the end of 1965, this number had blown out to more than 180,000.

1. The Gulf of Tonkin incident occurred on August 4th 1964, when the USS Maddox reported that it had been attacked by torpedo boats operating out of North Vietnam.

2. Two days later, US president Lyndon Johnson addressed the nation. He promised to respond to this “new act of aggression” and to seek a congressional resolution.

3. This resolution was secured on August 10th, with almost unanimous support. Though not a declaration of war, it authorised Johnson to deploy American military forces in Asia.

4. Johnson took no major action until after the November 1964 presidential election. Johnson won this election decisively after depicting opponent Barry Goldwater as a warmonger.

5. The first US combat troops landed in Vietnam in March 1965. US troops operated under restricted terms of engagement. As these were extended, troop numbers also increased, reaching 184,000 by the end of 1965.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Gulf of Tonkin incident”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/gulf-of-tonkin-incident/.